Sapphires and steel: industrial materials show their mettle

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Aluminium, carbon fibre and surgical steel are not materials traditionally associated with high jewellery. Nevertheless, the use of these and other components in jewellery is evolving, providing radical alternatives to more familiar precious metals.

“The world is changing so fast and jewellery should be changing too,” says Italian jeweller Fabio Salini, who works extensively with carbon fibre. “If you always approach jewellery in the same traditional way, you risk remaining static.” For this reason, innovative designers are experimenting with alternative materials to try to produce something original.

It is hard to imagine that industrial materials such as carbon fibre, which can be found in cars and aircraft, could be set with precious gemstones. Or that Corian, used primarily in kitchen worktops, could be carved and set with opals. Or that aluminium, more commonly associated with cans and utensils, could take on the status of a precious material with inspiration and hours of craftsmanship. Yet this is happening.

Salini says carbon fibre “has revolutionised my [design] language because finally gold has lost its predominant role of being the structure of my jewellery”. He came across the material, sold in rolls like yarn, about seven years ago in one of his artisans’ workshops and was drawn to its strength and lightness. However, shaping it into jewellery has to be precise and is a challenging process because, once it becomes solid, it cannot be changed. The designs are bold and conceptual, with gemstones set into the carbon using a gold interface.

Hard, beautiful and brilliant when polished up, steel is under-appreciated when it comes to jewellery, believes James de Givenchy. The New York-based owner of Taffin, best known for his playfully bright ceramic jewellery, says he has never thought of steel as a “not so precious” metal. He is using surgical steel and blue steel, a colour produced by heating stainless steel to a specific temperature for a specific time, to create the most delicate gem-set necklaces, bracelets and rings. The challenges, he explains, are learning to work with the metal, which requires a lot of heating and is difficult to manipulate. But he says his clients, mostly contemporary art collectors, are intrigued by the way the jewellery is made.

Australian jewellery designer Lingjun Sun had been experimenting with marble and ceramics during his MA studies in London, before discovering Corian, which he found lighter, less brittle and easier to carve. Finding a material that he could upcycle also appealed to him, he says. He also likes using white Corian “for its bold contrast to the vibrant colours of my opals and gemstones, which can be set directly into it without the need for gold”.

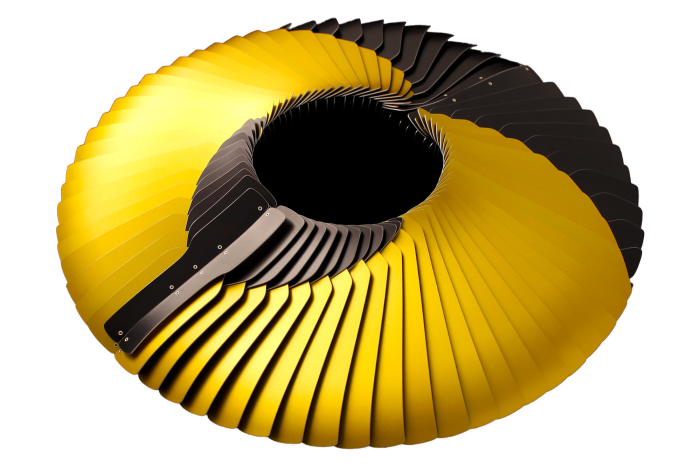

“If you are looking at the hierarchy of aluminium as a material, it is way down there,” admits contemporary jewellery craftsman John Moore, who produces large, futuristic wearable art such as his Lacewing collar in aluminium and silicon, and a dramatic Pagoda parasol-shaped necklace in anodised aluminium, completed during lockdown. Yet, historically, aluminium is a valuable material, sought after for its strength and lightness for industrial purposes.

What is used in jewellery is the purest form of the metal. Designers such as JAR, Hemmerle and Shaun Leane use aluminium to spectacular effect. Techniques are constantly refined. Moore, for instance, uses hard, pre-anodised sheets that he dyes and crafts. “I challenge myself to see how I can create forms that are very sculptural and 3D with volume, but using an assemblage of shapes,” he explains.

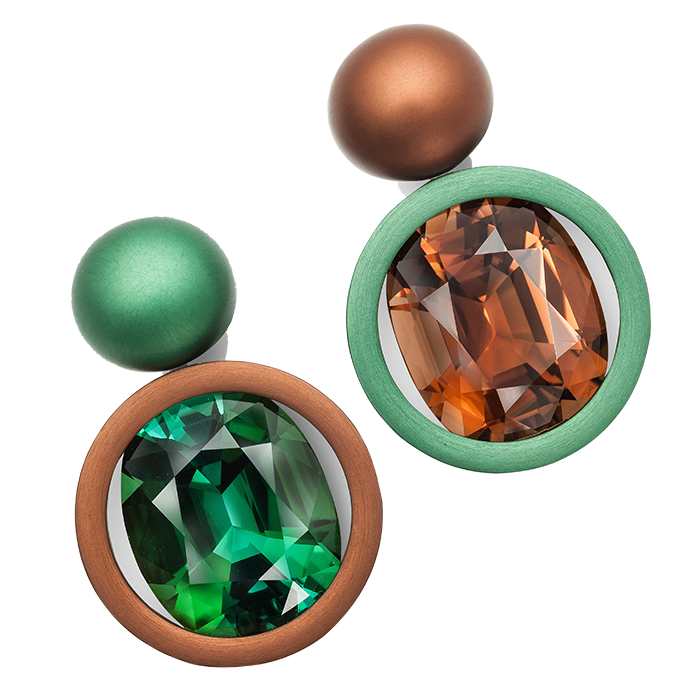

Alternatively, jewellers such as Munich-based Hemmerle use raw aluminium, when it is still malleable, to sculpt their creations before setting the gemstones and anodising the results. “Its malleability enables us to focus on innovation and create intricate works which are delicate in design yet highly durable,” says Yasmin Hemmerle, who runs the jewellery house with her husband Christian. “Through a process of anodising we create aluminium in a variety of hues that complement the natural colours of the stones. The most challenging part is anodising aluminium.”

Hemmerle and Parisian jeweller Boucheron are among those that like to experiment with unconventional materials. Claire Choisne, Boucheron creative director, has tried synthetic low-density materials such as aerogel, also used by Nasa, which she encased in rock crystal for a high-jewellery pendant. “I am a fan of innovation and have a personal interest in science,” says Choisne, who admits it took two years to find a material that could reproduce the sky’s infinite palette of blues for this design.

And some of her innovations date back longer. Take, for example, replicating flower petals in titanium for a series of rings. Metal had to be bonded to natural petals that had been specially preserved by a “petal expert” using a technique that took 10 years to research.

Comments