Making merry: the best London restaurants to raise a glass (or several) in

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is part of a guide to London from FT Globetrotter

It was late summer in 2011 and quite a lot of north London was on fire. Mass protests following a police shooting in Tottenham had escalated over successive nights into a spree of vandalism and arson that for a brief time felt like it might consume the city.

We lived in Shepherd’s Bush, in a first-floor flat above a nail bar, a kebab shop and a jewellery pawnbroker that was an unideal combination of vulnerable and flammable. So, rather than stay home and listen to the approaching sound of breaking glass, we went across the street to Patio: a Polish restaurant known for dense, agriculturally presented food and for its ever-present host, Ewa.

A trained mezzo-soprano who had fled Krakow in 1970, Ewa ran Patio with matronly authority. As the first few rioters ran up the street wielding traffic cones, Ewa broke off service to stand at the threshold cross-armed. When more followed, she rolled down the shutters and locked the door. It had been decided. The world beyond her domain no longer mattered. However long it took for the storm outside to pass, Ewa circulated the room pouring free shots of bison-grass vodka while her husband Kaz, still in chef’s whites, played waltzes on the upright piano.

Patio, which sadly closed in 2017, has been in my thoughts over the past few months. Like many people who care too much about restaurants, I had a list to visit as soon as lockdown restrictions lifted. Bored of my own limitations of skill and imagination when cooking, I wanted every meal to be uncustomary. I wanted once again to sit on a Tolix stool beneath bare filament lightbulbs, being brought unfamiliar combinations of foraged ingredients by a chef with arm tattoos like an Iron Maiden mood board.

Then it happened and it was a bit rubbish. By the end of lockdown, the restaurant trade was in such a ragged state that even good places were bad. Damage was too visible from staff and supply shortages, as well as from the withering of collective muscle memory that daily service builds.

Opening at all in the throes of a pandemic was a triumph. We made allowances. Nevertheless, it palled quickly to always be wondering whether the person tasked with driving the stove that day had ever seen one before. Better instead to go where the key skill required was to open a bottle, and where everything looks best through the bottom of a glass.

Good food alone can’t make a great restaurant. Much more important to me is the maintenance of an overarching, unbreakable sense that nothing can go wrong. An ambitious chef is only ever as good as the kitchen brigade available that day, whereas a talented restaurateur can build atmosphere incrementally over decades. A great restaurant is one that cossets a diner within its safe harbour for a few hours then releases them back into the wild a happier person, irrespective of how well or badly they ate.

And what creates atmosphere? More often than not, it’s alcohol. A person can get rolling drunk almost anywhere, of course, but there’s an alchemy to places where the mood suits getting comfortably numb. Patio had it. Each night, through strength of personality and gallons of vodka, it formed into an insulating bubble. Its shared goal of boozy, tranquillising escapism was powerful enough to mute the outside world, even when it was literally on fire.

Here’s a few of my favourites that can pull the same trick. It’s a disparate list with only a few common traits. All are overseen with benevolence by people who know to act like the zookeepers, not the animals. They have staff who will non-judgementally make a martini at 11am and a triple espresso at midnight. They all improve once blurring at the edges. Their cooking can be fancy or rough, reliably good or the opposite, so long as days pass easier from within their protection. Cheers.

40 Maltby Street, Bermondsey

40 Maltby Street, London SE1 3PA

Good for: Knockout small plates and a wine less ordinary

Not so good for: Hearing yourself think

FYI: Those willing to disregard the common warnings about mixing grape and grain can make a detour to Druid Street’s many craft breweries on the opposite side of the tracks

In a railway arch next to an over-popular food market is 40 Maltby Street. It’s a wine shop first, a bar second and a no-reservations restaurant only after 5.30pm between Wednesday and Saturday. The owner is Gergovie Wines, an importer with enthusiasms for everything organic and low intervention, so be braced for occasional notes of compost, burnt orange and attic dust. The broom-cupboard kitchen follows in the tradition of diligent cooks like Simon Hopkinson and Rowley Leigh and makes use of unexotic things — cod’s roe, turnips, haggis — that taste much better than they look.

All in all, it shouldn’t work. There should be little pleasurable about perching on a high stool in a draughty railway arch, drinking wine that could pass for raw cider while, all around, London’s most braying foodists shout to be heard over the rumble of trains above. Yet 40 Maltby Street works. Mostly it’s thanks to the faultless food but, even after the kitchen closes, it still thrums with the goodwill of people who have contrived to make their living out of drinking.

Albertine, Shepherd’s Bush

1 Wood Lane, London W12 7DP

Good for: Anyone seeking a fuss-free archetype of a local hangout

Not so good for: Luxuriating. Seating downstairs is church-like while upstairs has all the natural warmth of student accommodation

FYI: The name refers to a Proust heroine, which once led the journalist and historian Daniel Johnson to assume wrongly when writing in The Telegraph that it must be a lesbian bar. A flurry of BBC-postmarked letters followed

Not far from Patio’s old site is Albertine, a Francophile wine bar of a similar age that for decades was the unofficial annexe of the BBC Television Centre canteen. It began a slow decline in 2013 when the BBC moved north and looked doomed when previous owner Giles Phillips announced his retirement a few years later. Then chef Allegra McEvedy stepped in to protect a family legacy, her mother having first opened the bar in the 1970s.

McEvedy improved the food dramatically and changed nothing else. The rickety ground-floor bar and bottle shop still has chalkboards advertising cheese and charcuterie alongside a dozen or so wines by the glass. Upstairs is a simple, homely dining room on which tens of pounds have been spent. Menus lean towards comfort, but with occasional cheffy flourishes that speak of care that the likes of whitebait, bavette and duck rillettes rarely receive. Albertine’s only trick is to make things better.

Andrew Edmunds, Soho

46 Lexington Street, London W1F 0LP

Good for: Channelling the spirits of old Soho through the medium of wine

Not so good for: Al fresco. Two tiny pavement tables are so exposed to the city they may as well be performance art

FYI: The booking system involves names written on the paper tablecloths. Anyone visiting in circumstances where they would rather not be easily identified, which most nights seems to describe nearly everyone, is advised to use an alias

Mentioning Andrew Edmunds is an invitation to hear a Londoner’s life story. It’s the opening scene in a million anecdotes about messy dates, inglorious ventures and evenings that continued through to sunrise.

Soho’s reputation for bohemian excess was already more legend than truth in 1985, when art dealer Andrew Edmunds added a wine bar and kitchen to his prints gallery. Rising property prices and videos by mail order were combining to squeeze out a sex industry that had defined the area. Media companies had sprung up between the clubs and drinking dens that had once served to circumvent postwar licensing laws. The area remained a gathering point for alcoholic culturati (actual and aspiring) and a green zone for homosexuality (illegal until 1967) but it was already carrying a heavy burden of nostalgia. “Soho isn’t what it used to be,” the critic Jeffrey Bernard is said to have complained, “but then it never was.”

It’s the old, idealised Soho that is survived by Andrew Edmunds. Staff and customers work together each day to preserve an atmosphere of high -spirited dissoluteness that’s a counterpoint to the lads-on-tour pubs and proto-franchise dining concepts that have moved into the area. It’s a place radiating that rarest of qualities, charisma, which has somehow been sustained for nearly four decades on collective willpower. And wine. Lots of wine.

Above ground is a cramped, dark room where it’s barely possible to slide a hand between each table. Downstairs is similar but with added illicitness. The short, handwritten daily menu nods at Britain then wanders the continent in search of things within the kitchen’s capability, such as braised hare shoulder and confit duck. Everything is held together by a monumental wine list whose pricing is gentle and completely without logic. The kind of drinker who Googles retail prices before ordering will have a lot to work with here, and will be missing the point entirely.

Le Café du Marché, Smithfield

22 Charterhouse Square, Charterhouse Mews, London EC1M 6DX

Good for: Lunches that begin with an exchange of business cards and wind down shortly before the last train home

Not so good for: This is perhaps not a problem for everyone, but it’s best to be aware that evenings often involve jazz

FYI: The upstairs function room has its own entrance and is completely self-contained, so lends itself to the kind of inconspicuous celebrations preferred by people who manage banks

Eulogies for the boozy business lunch were being written long before Le Café du Marché opened in 1986 and its owners have needed to read none of them. Up in a cobbled mews on the City’s western edge is a timeless French brasserie that does nothing more surprising than continue to exist.

Specials such as côte de boeuf and pommes Anna might sound naff in a city captured by novelty. But Café du Marché is grown-up and comfortable enough in itself not to care about trends, which attracts a type of diner who seeks to do the same. Those who understand the benefits of a three-bottle working lunch can find it celebrated here, via a discreet gateway into provincial France 10 minutes from the office that hides in plain site.

Canton Arms, Stockwell

177 South Lambeth Road, London SW8 1XP

Good for: All the things expected of a neighbourhood pub with a very capable kitchen on the side

Not so good for: People who don’t like pubs. It is, incontrovertibly, a pub

FYI: Ever-present on the menu since current management took charge in 2010 is the toastie, sometimes including a foie gras option that in the early days caused considerable debate. Look out for the framed cartoon of a toastie that is the landlord’s solitary concession to interior design

The very best pubs are refuges. Lots of pub companies place their ambitious landlords and competent cooks in Chelsea, Barnes or Marylebone to soak up the local wealth. The more adventurous ones draw from a wider constituency, using lowish rents in rougher neighbourhoods to make somewhere worth the effort of a journey.

Opened in the late 19th century, the Canton Arms now looks out onto a 1960s council estate on a gradually gentrifying strip of Stockwell, south-west London. It’s more of a local bruiser than its sibling pub, The Anchor & Hope in Southwark, though they share the same unpretentious approach to food. Expect a curry or lasagne among the list of gastropub staples such as beef cheeks. Expect also for many of the customers to be in for an after-work pint, not a culinary journey, which sets it apart from most of London’s guidebook-bothering gastropubs. Cooking is solid enough to have received a nod from Michelin — but even when dinner will be no more ambitious than a sausage roll and a ramekin of peanuts, it’s still easy to be glad the Canton exists.

Centro Galego de Londres, Kensal Green

869 Harrow Road, London NW10 5NG

Good for: Spanish food and drink in their most authentic, domestic, disarmingly frowzy forms

Not so good for: Refinement. Fine dining this is not

FYI: The restaurant has a recently dormant charity offshoot dedicated to advancing “the education of the public in the Galician language, heritage, culture and the arts”.

Choosing somewhere Spanish was the biggest challenge. With tapas, the Iberian peninsula perfected pub food early then resisted wholesale evolution until the early 2000s, when la nueva cocina came along to ruin everything. Accompanying each drink with morsels of salt, pork, peppers and fried things upends the formalities of dinner and allows an evening to dissolve gradually.

Nothing in London happens gradually, however. Kitchens are cleaning down by 10pm and tables need to be turned at least once a night. Though London has many excellent Spanish and Spanish-ish places — Sabor, Moro, José, Tendido Cero — it also suffers more than most cities from tapas as a concept, which deploys small plates as a kitchen convenience and a marketing device. Food arrives in unpredictable quantities at random intervals over a period of 90 minutes, followed by a bill that’s a third bigger than the menu prices had implied.

Avoid all that at Centro Galego de Londres, a social club for the Galician diaspora that according to the wall plaque was founded in 1968. In recent decades it has looked out on a bleak corner of west London, in a bar-café filled with football memorabilia that looks little different to the many migrant community canteens in nearby Harlesden. No one comes here by chance, which means no one feels unwelcome when they arrive.

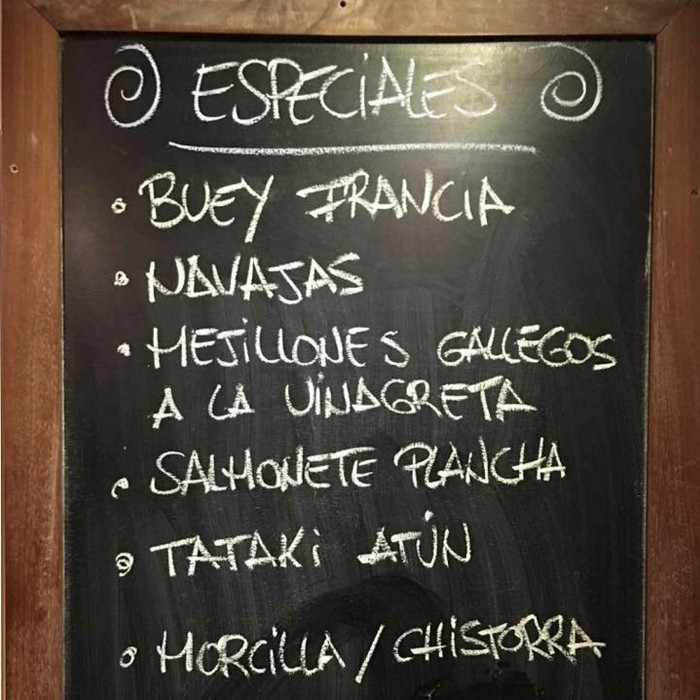

On the regular menu are Spanish greatest hits delivered in the no-nonsense style of a pub cover band: fist-sized croquetas and empanadas, boiled octopus, custard flans and limitless alioli in paper cups. A chalkboard next to the kitchen pass has daily specials from Galicia, once one of Spain’s most disadvantaged regions, where poverty and perpetual drizzle built a Celtic appreciation for root-vegetable broths using offcuts such as pig’s ear and veal cheek. Drinks include queimada, a brandy punch with occultist connections. There can sometimes be interesting things to eat and drink here, though that’s not the point of the place. Straightforward generosity alone is what makes it difficult not to have a good time.

Noble Rot, Bloomsbury and Soho

51 Lamb’s Conduit Street, London WC1N 3NB and 2 Greek Street, London W1D 4NB

Good for: Thoughtful cooking and rare wines sold by the glass

Not so good for: Telling your friends all about it. They already know

FYI: Restricting yourself to the set menu and one glass of house will present both a bargain and a test of willpower that very few are able to pass

Recommending Noble Rot is like telling visitors to Pisa to check out the tower. The Rotters, two restaurants backed and managed by a food-industry supergroup, hardly need more advertising having made it onto all the best-of lists. But when asking around fellow lushes for suggestions on where might satisfy this article’s brief, its was invariably the name offered first.

Dan Keeling and Mark Andrew, a wine-merchant buyer, launched Noble Rot first as a fanzine for wine and food, and then in 2015 as a bar-restaurant on the eastern edge of Bloomsbury. Last year they opened a second branch in what once was the Gay Hussar, a narrow Soho townhouse where eastern European indocility and murk made it the leftwing establishment’s equivalent to a Pall Mall club. Though choosing between the old and new one is largely a choice of whether to prioritise atmosphere or comfort, both are easy places to lose an afternoon.

Menus take guidance from Stephen Harris of The Sportsman pub, a pilgrimage site for forthright English cooking on the Kent coast, which means expect the likes of slipsole, pheasant and brown shrimp. Bar food tilts a little more towards Europe and, in combination with an expansive selection of wines by the glass, makes each visit a battle between a desire to keep going and fear of the eventual bill. The former usually wins out.

Which London restaurant do you like to get slightly sozzled in? Tell us in the comments below

Comments