Paula Rego: ‘Does art offer the best revenge? It’s the only method I’ve found’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Dame Paula Rego has died, aged 87. This article, one of her last interviews, was published in December 2021

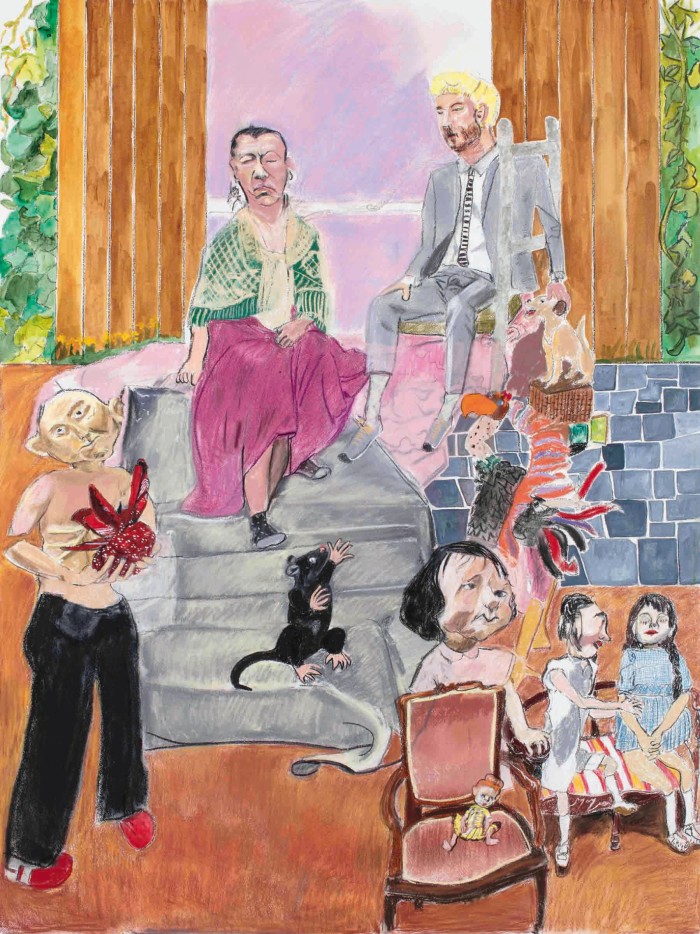

There have not been many certainties in 2021, but one thing has been made crystal-clear: Dame Paula Rego, 87 next month, is one of the greatest painters of her generation – not just in Portugal, her native country, or Britain, her home since the 1950s, but the world. A huge, critically acclaimed retrospective this summer at Tate Britain reminded us of the savagery, strangeness and charm of her vision (as well, in the words of the FT’s art critic Jackie Wullschläger, as “a lifetime’s flair for sensitively rendering the unidealised female form”).

If Rego is often inspired by the fantastical, conjuring scenes from her favourite Portuguese folklore, classic literature or even Disney films, she never shies from the bracingly real: from questions of desire, dominance and need; from issues such as FGM or, most famously, abortion (her series on that theme, made in the late 1990s, is widely credited with helping persuade Portugal to change its laws). It’s odd to think that, when she had her breakthrough show at London’s Serpentine Gallery back in 1988, she apparently made storytelling in art seem credible again. To look at her paintings, you think: what else is there?

Rego hasn’t stopped working but she has been slowed by ill health, Covid and a fall that saw her badly hurt her face. Despite this she still travels to her studio in London where she works with her long-time model Lila Nunes; they’ll finish the day with a glass of champagne. It’s here that she has been exclusively photographed for us, among the many dummies and other props that populate her work – where she brings so many dreams and nightmares into being. She also answers a special Q&A of our own to coincide with the publication of a book next month where she responds to questions from many of today’s finest female artists, from Chantal Joffe to Marlene Dumas via Kudzanai-Violet Hwami – we share some of these too.

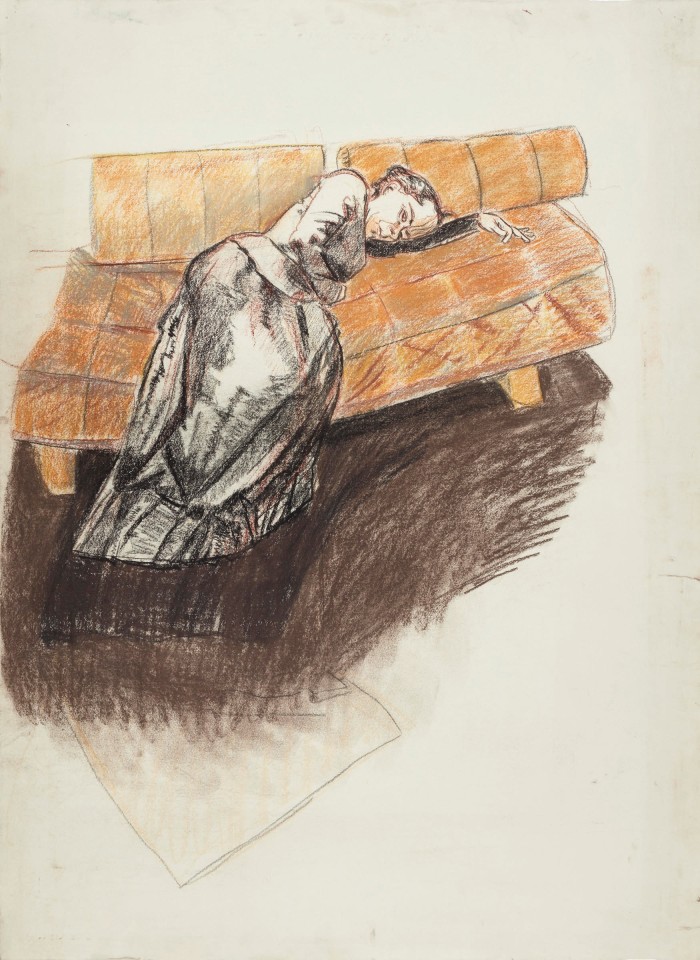

At the moment we can also see another show of rarely seen past works, The Forgotten, at Victoria Miro in London. Self-portraits figure for once, inspired by Rego’s temporary disfigurement; meanwhile, her Depression series dates from one of her depressive spells. She’s had several, not least when her husband and champion, fellow artist Victor Willing, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, a disease that would finally kill him in 1988. The works also bring to mind her beloved father, equally susceptible to mental crises, who tried to shield her, in childhood, from the cruelties of António de Oliveira Salazar’s regime. But these things could never be kept from Rego – they sit far too close to the surface of her mind, as of her pictures. That tension has sustained her for decades.

Louis Wise: It is often said that your work is brave. Do you agree with that?

Paula Rego: I am not a brave person. I am rather timid and shy, unless I’ve had too much red wine. Discovering I could do whatever I liked in my work came as a relief. If it turned out well, it gave me great pleasure.

Your new show is called The Forgotten. Are such people the heroes – or at least the subjects – of your work?

I’ve always enjoyed flipping things on their head. Putting the dog in charge, so to speak. It makes for a more interesting story.

Do you view your periods of depression as part and parcel of the creative process? Can it be helpful?

It isn’t helpful, it’s depressing, but it’s part of the same thing.

Have you reconciled yourself to the self-portrait? Or is there something just too obvious about the genre?

I’m not sure if they are obvious but I was never interested in doing them. I didn’t like my face.

One of the great joys of your new book is to be questioned by so many extraordinary female artists. Has the sexism of the art world gone now?

I doubt it very much.

What’s it like being a Dame?

It’s smart.

Your father recurs very movingly in your memories – and in works in the new show. Has ageing changed your perception of him?

Not at all. I still see him in the same way. I loved him. I could count on him to rescue me. He was always very kind to me.

Do you agree with your mother’s line that “a change is always good, even if it is for the worst”?

No. Except in my work. There, change is inevitable.

Clothing matters deeply in your pictures – and you and Victor seemed a very stylish couple. Do you take pleasure in portraying clothes?

I’ve always loved clothes, it’s one of the few things I had in common with my mother. She and my father would travel to Paris every year and she’d buy that season’s hats. There are still many hat boxes on top of her wardrobe in Estoril. We had a seamstress (Menina Francisca) come to the house to make our clothes, as back then you couldn’t buy ready-made in the shops. My mother bought Vogue and Elle patterns so we could be up to date.

You feature so many animals and beasts in your work –which have marked you most in life? Did you have pets as a child, or when living in your family estate at Ericeira?

I was a very shy, timid child. Frightened of everything, even flies, my mother said, but she thought I should have a pet to keep me company. He was called Ron Ron. I was terrified of him. He was a pure-breed Scottie and kept being kidnapped and held for ransom. He was very highly strung and the kidnappings didn’t help. In the end he jumped to his death from a balcony: suicidal dog. In Ericeira my grandparents had a very old dog called Bruno who had lots of tics; and later Vic bought Jack from the Lisbon zoo. Jack was his dog really, a very beautiful Portuguese mountain dog. He used to chew into small dogs if they strayed into the quinta.

You have said, “You can punish anybody in a picture.” Does art always offer the best revenge?

It’s the only method I’ve found.

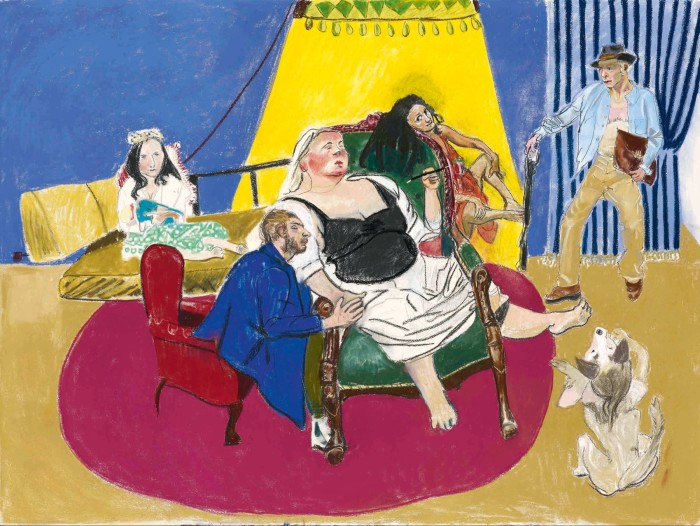

You have been working on a series based on the Seven Deadly Sins recently – which of these have you been most susceptible to?

I would say gluttony. When I was at finishing school I ate everyone else’s leftover puddings and put on so much weight that my mother didn’t recognise me. At the Slade I’d buy a family pack of Neapolitan ice cream and eat the lot. I love ice cream.

Do your own pictures remain a mystery to you, or can you explain every part?

It is true that sometimes you look at old work and reassess it. Sometimes it isn’t as bad as you feared.

Do we still misunderstand childhood?

Maybe.

Try to simplify and sentimentalise it?

Not me.

Is painting a picture still “like being a man”?

The bit of me that feels like a man.

Do you still have any unfulfilled ambitions?

No.

Which artist, living or dead, would you most like to have a glass of champagne with?

Picasso or Botticelli.

What has been your deepest pleasure?

Having my knickers taken down by my husband.

What the artists asked…

In an extract from her new book, Paula Rego takes questions from those she’s inspired around the world

What is your attitude to beauty in art? In your own work and in the work of others.

I don’t have one. I’m not trying to make things beautiful, that’s not particularly interesting, and I expect I would find things beautiful that others find ugly.

Is grief a source of inspiration?

No, it isn’t.

Why don’t you paint nudes?

I have done, if the story needs it. [The poet] Tony [Rudolf] was nude in Metamorphosis. Clothes are very useful. They say a lot. They show character and status. Most of life is clothed.

Did you find it helped your depression, making those drawings, or made it worse?

It always helps to work.

You have spoken about always showing Victor [Willing] your paintings for his help/advice, did anyone replace him?

Unfortunately not, no.

Do you ever get lonely being a painter?

I don’t know what to say to be helpful. People find their own way. It doesn’t help anyone to be discouraging. I don’t get lonely being a painter, but in the past I did miss other painters to talk to about work.

I love the dummies in your work, they’re so fantastical and uncanny. Do you make them for a picture, or do they exist for their own sake and find their way into your work?

I usually make them, or have them made, for a particular role but then they become jobbing actors and get cast in different roles or used in installations. I become very fond of some, while others creep me out and Lila has to hide them. She made a wonderful cricket for me, but it had a bad feeling I couldn’t use, so she took it away again.

Do you paint your subjects the way you do… hoping to push down walls of repression and encourage women to be freer in their different versions of themselves?

The only thing I’ve ever made in the hope that it would change minds were the abortion paintings. Otherwise, I paint women as I see them. Those are women I know.

I wonder, when you were making work in the beginning… was there certainty about what it all meant? Were there expectations that you felt you had to fulfil, and how did you overcome or fulfil them and still remain true to your work?

My first art lessons were at St Julian’s School in Portugal. They were encouraging and allowed me to paint anything I wanted. I used to fill the hall with murals. The Slade was more proscriptive. They wanted me to draw from the casts of statues. I couldn’t get on with that. I carved a space for myself in a corner and hid my pictures behind the statues. Did my own thing. Victor Pasmore, who was very critical of my work, said, “Are you still doing that stuff?” It was the only “stuff” that had some meaning for me. I couldn’t pretend I was an abstract painter. I wasn’t. “Trust yourself,” my husband said, “and you will be your own best friend.”

Paula Rego: The Forgotten is published by Victoria Miro on 18 January 2022 at £65. The exhibition at Victoria Miro, London, continues until 12 February 2022

Comments