Abraham Cruzvillegas on making art out of trash

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

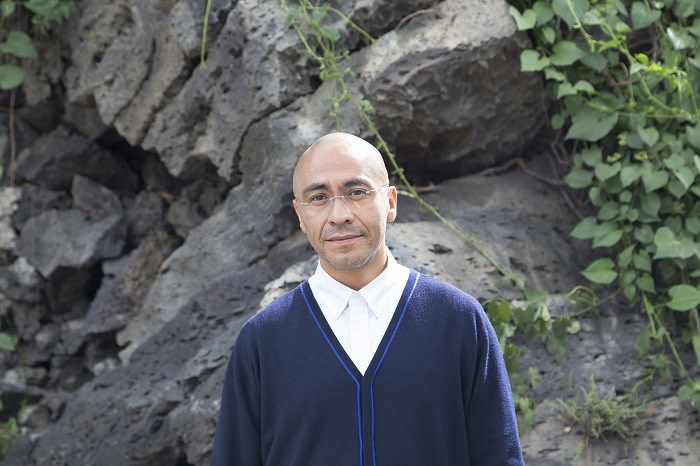

The Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris is not where you would expect to find Abraham Cruzvillegas. The Mexican artist is known for sculptures inspired by slums, shanty towns and favelas, for which he scoops up discarded objects found on streets and in dumpsters. As well as exhibiting in leading biennials, such as Sharjah (2015) and Shanghai (2012), and dOCUMENTA 13 (2012), in 2015 he filled Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with soil shovelled out of London’s public parks and gardens.

The contradiction between this wilfully humble practice and the Brahmin-high ambience of the honey-stoned French academy, where Cruzvillegas has a teaching post, is intriguing.

The surprises don’t end there. When I find him in his atelier — a scruffy space where a bicycle and a shopping trolley are among a miscellany of items littering the floor — he is in the middle of giving a seminar to a group of students. When he tells me they’ll be staying for our interview, I am a little thrown. “It’s good to improvise,” he says, leaving me little choice but to comply or look as if I’m spoiling the party. As it turns out, it is invigorating to have these quiet observers — even if most have wandered off by the end.

Our encounter has been triggered by the decision to restage “Autorreconstrucción: To Insist, to Insist, to Insist”, a multidisciplinary installation devised by Cruzvillegas and the Argentine choreographer Barbara Foulkes, during Art Basel Miami Beach. The installation, curated by Philipp Kaiser, is Art Basel’s first free public exhibition.

The work emerges out of Cruzvillegas’s ongoing fascination with the process he terms “Autorreconstrucción”, which translates as “self-construction”, and encompasses his habit of creating sculptures using locally found materials. Its seeds were born in a childhood where his own home had been built from what was at hand. “I was completely in that way of making,” he explains. A slight, sharp-eyed figure in glasses and check shirt buttoned up to his collar, Cruzvillegas speaks rapid, Spanish-inflected English with elaborate sentence constructions that talk back to his Latin roots.

The Miami installation was put together at La Pista, a dance space in Mexico City then enjoyed further performances at New York non-profit The Kitchen in April 2018. But its seeds were sown in May 2014 when Cruzvillegas received a note from avant-garde choreographer Barbara Foulkes asking him “if I would like to become a choreographer, at least once in life . . . Then we met for the first time to talk some weeks after that. It was fun!”

Just as Cruzvillegas does with his precarious sculptures, Foulkes’s practice explores weight and equilibrium. “Normally she is hanging herself from the ceiling with ropes where she spins and balances according to the nature of space and gravity,” he explains.

When I ask Foulkes via email why she wanted to work with Cruzvillegas, she replies that his vision of “autoconstruction” has a “choreographic sense”. “I see the choreography as a construction, like a process of the transformation of the space, of senses, of meetings,” she says.

In Mexico, the pair started by building a hanging sculpture and then destroying it “as a private thing for ourselves and some friends”, Cruzvillegas recalls. When he received a call from Kitchen curator Tim Griffin asking if he might consider making some work in New York, he “immediately thought” of his collaboration with Foulkes.

In the Chelsea space, the duo constructed another hanging work which Foulkes then destroyed in a twice-daily performance. But they also involved Andres Garcia Nestitla, a musician from the north-east of Mexico to improvise sounds “for our destruction”.

Unable to get Garcia Nestitla a visa, they ended up live-streaming a video of their performance to him in Mexico and livestreaming his improvisation back across the virtual border between the two countries. “So [the work] became more elaborate, more complicated and more political,” says Cruzvillegas.

The Mexican artist has made a conscious decision to remain as detached as possible from the work. Although he built the first version of the sculpture at the Kitchen, subsequent editions were created by other people. He also avoided scavenging the streets for materials. The building blocks his co-workers came up with encompassed “a ladder, a washing machine, a picture frame, a couple of chairs, napkins basket balls, tennis racquets, shoes and ropes. I didn’t choose anything myself. We worked with whatever they gave me.”

Such odes to trash might be in tune with Manhattan but I wonder how it will play in the less louche environs of Miami Beach’s Convention Centre, where “Autorreconstrucción” is due to be installed in the newly restored Grand Ballroom. Cruzvillegas is fantastically vague when quizzed on the details of “Autorreconstrucción”’s Miami chapter. Asked who are his hunters and gatherers this time, he replies: “I don’t know. Maybe the same people from the Kitchen or from the place there. The ball hall? I don’t know the name. The idea is not to include my own taste, my own choice. I accept everything.”

He is hoping that Diego Spinoza, a composer and percussionist from Mexico, will be able to participate. However it’s possible he won’t be given a visa. So “someone from Miami” will step in.

It’s easy to situate Cruzvillegas’ hands-free ethos in the laissez-faire shenanigans of 20th-century Surrealism and conceptualism. But it is also the poignant offspring of a more personal narrative. “My father was a commercial painter,” he remembers. “He did landscapes and birds. He carved in wood: figures of saints, Christs and the Virgins. My siblings and I were familiar with the smell of dust and paint.”

Given that painters are so often lauded as beacons of creative expression, it’s surprising to hear Cruzvillegas say that watching his father make art “by command” — as he puts it — could make him shun the craft.

At university in Mexico, Cruzvillegas studied art and philosophy. (He thought of studying biology, he tells me, before adding that 17 is “the worst age to make a decision. You want to drink beer and hang out with your friends.”) His early work saw him take his father’s handmade pieces and recycle them. “They were like objects to me,” he says.

Anticipating any Lacanian musings I might make about the death of the father, he continues. “I felt it was about psychoanalysis. It was properly

destroying my father’s work but also about giving it a new life.”

What did his father make of his work? “He laughed at me,” he says with a grin, before adding that by the time he started his disrespectful recycling, his father had a new job as a university professor. With its commitment to the collective over the individual, the political implications of his art are undeniable. Yet he nevertheless describes himself as “the frivolous one, the petit bourgeois” in a family where the others are “human rights defenders and advocates”.

Clearly there is a material abyss between life in a favela and the chichi streets of Saint Germain. Does Cruzvillegas never worry that he is misappropriating the aesthetics of poverty?

“It’s not about poverty,” he says fervently. “It’s not about that. It’s more about the ingenuity of people in scarceness. Not scarceness. It’s about the very rich tradition of making with nothing — that is human. It’s not about Mexico. It’s not about technique.” He takes a breath as if exhausted by his skein of negatives. “It’s more about politics.”

Urged to continue, he flows on. “Where do all those terms originate? Favelas? Slums? It’s the unfair distribution of wealth. And this happens everywhere for many reasons. In my country, it’s because of corruption, authoritarianism and many other things that are rhizomatic of that.”

His work, he concludes poetically, offers “a possibility of how hope can take space and shape”.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments