Covid-19 unmasks weaknesses of English public health agency | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When news began to spread in January of a lethally contagious coronavirus in China, ministers and scientists rushed to reassure the public that England was unusually well placed to manage the threatened global pandemic.

Public Health England — an agency conceived as the answer to the US’s respected Centers for Disease Control and Prevention when it was founded in 2013 — had distinguished itself in the fight against Ebola in Sierra Leone, earning plaudits from one leading scientist who described its expertise in microbiology and virology as “spectacular”.

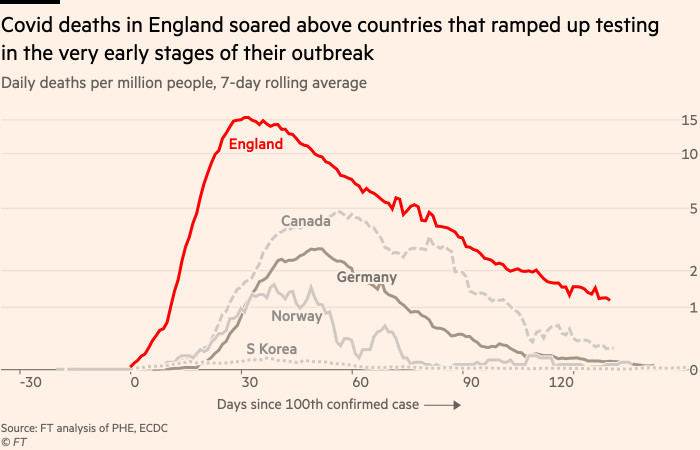

But as ministers scramble to explain England’s poor response to the virus, which has officially killed almost 41,000 people there (the total UK-wide death toll is over 45,000), Boris Johnson’s under-fire government is increasingly seeking to blame PHE for much of what has gone wrong.

On Tuesday health secretary Matt Hancock gave the clearest signal yet that PHE would not continue in its current form. It was “really good as a scientific organisation”, Mr Hancock told MPs, but was not well placed to deliver a nationwide Covid-19 testing system.

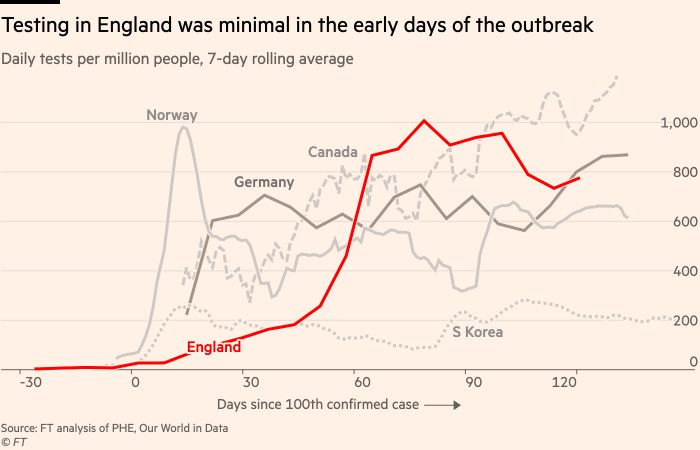

“It was not set up to be an organisation ready to go to mass national scale and we didn’t go into this crisis with that mass of testing capability,” Mr Hancock said.

The prime minister had already admitted that parts of the government’s coronavirus response had been “sluggish”, remarks widely seen as a dig at the public health agency.

Some close to PHE believe a significant moment for the way the agency was publicly regarded came as early as March 25, when Professor Sharon Peacock, director of the national infection service at PHE, answered questions from MPs on the House of Commons science and technology committee.

Prof Peacock promised antibody tests would soon be available through high street pharmacies — an assertion disputed within hours by the chief medical officer. Asked in the same session with MPs why England had rejected South Korea’s apparently effective mass testing model, she replied it was “a good question” and promised to produce a scientific assessment underpinning that decision. The committee says she has yet to do so.

Greg Clark, committee chair, said the hearing “shook confidence” and was “certainly material in raising questions about the kind of dependable role of PHE in all this”. Prof Peacock declined to comment but the agency told the Financial Times she had made “a big and valuable contribution” to the coronavirus response, “including getting testing rolled out across the NHS, and now carrying out vital genomic research”.

A fumbled response

But the story behind England’s fumbled response to the crisis goes far beyond PHE, let alone one official’s appearance in front of lawmakers.

Interviews with more than 15 people who are familiar with the workings of PHE reveal an array of issues that have bedevilled the Westminster government’s wider handling of the crisis. These include an impulse to centralise, a wariness of engaging with industry and the impact of a decade of fiscal austerity, which has cut the agency’s budget by 40 per cent in the seven years since its inception.

PHE came into being as part of a wide-ranging, and controversial, shake up of the NHS devised by then-health secretary Andrew Lansley at the start of the 2010s.

Unlike its predecessor, the Health Protection Agency, which had been independent, it was to be an executive agency of the Department of Health, reporting directly to the health secretary. It also had a wider brief than the HPA, which had focused on communicable disease. PHE was additionally handed the health promotion brief, giving it a leading role in tackling obesity, smoking and alcohol abuse.

Latest coronavirus news

Follow FT's live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and the rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

The agency denies it has been stretched too thin, pointing to a glowing pre-pandemic assessment by an international peer review body which concluded it “rivals any in the world”.

Underfunding

However, there is a widespread consensus among scientists that the deep funding cuts it has endured weakened its ability to respond when the virus took hold.

Lord Lansley told the FT that the Treasury had reneged on a commitment to protect PHE’s budget. “The agreement I had in 2010 was that public health was inside the ringfence and would be protected in real terms.”

Peter Openshaw, professor of experimental medicine at Imperial College London and a member of the government’s new and emerging respiratory virus threats advisory group, suggested the underfunding spanned multiple administrations.

“A few decades ago our public health services were the envy of the world but they have been repeatedly reorganised, subjected to various cuts and pressures which have made it very difficult for them to function at the level they used to.”

Another scientist said that PHE had seen many experienced people leave through early retirement as the agency sought to cut its budget, putting pressure on those who remained: “As the epidemic grew, the numbers of things that they were being asked to do grew rapidly . . . At one point each person had about nine jobs and so they were just overwhelmed, essentially.”

Tracing stopped as case numbers rose

Among the charges levelled against the agency is that it stopped tracing contacts of all people who had tested positive for coronavirus once case numbers began to rise sharply.

Duncan Selbie, PHE’s chief executive, who has made no public appearances since the crisis began but speaks almost daily to Mr Hancock, according to colleagues, declined to be interviewed for this article. In a written statement he said: “We moved to targeted contact tracing only when the ‘delay phase’ began, not because PHE could not cope but because mass community transmission made that inefficient over other measures, principally lockdown.”

But Patrick Vallance, the government’s chief scientific adviser, appeared to contradict that last week. “The tracing system in place in February was not one that we didn’t like, we wanted more of it, but it was very difficult to scale that on the basis of what Public Health England was able to do at the time,” he told the science and technology committee.

Critics also questioned why at the outset of the crisis no one in government thought to involve England’s more than 130 local directors of public health, who between them commanded up to 5,000 staff with proven expertise in curbing outbreaks of sexually transmitted diseases or salmonella, to boost the ranks of PHE’s own contact tracers.

Kate Ardern, director of public health for Wigan who is in charge of the emergency response for Greater Manchester, said: “At the point at which it was stopped, there were 290 contact tracers in PHE for the whole of England. Now, that was clearly going to be insufficient but nobody at a national level seemed to have thought, ‘well, that’s not going to be enough, we’ll need more, where are there likely to be more contact tracers?’”

She insisted responsibility for this oversight went far beyond PHE, adding that she and her colleagues worked well with the agency’s own regional outposts.

But the initial reluctance to involve local public health departments highlighted a wider failing of the government’s response to coronavirus. “Nationally nobody considered the need to have a conversation with the local system about who else might be mobilised quickly, and then how we work together to build surge capacity,” Prof Ardern added.

One former cabinet minister suggested that the civil service was instinctively cautious about risking “variable outcomes” by relinquishing the reins.

The failure to reach out more speedily to private labs, to increase the number of tests that could be carried out, may in part have reflected a similar determination not to risk a dilution of the standards the agency prided itself on setting and upholding, some scientists believe.

Mr Selbie said: “PHE operates national specialist labs and not mass diagnostics.” He pointed to the agency’s rapid development, and rollout, of a diagnostic test, the first outside China, across 40 NHS labs, which “was the fastest deployment of a novel test in recent UK history”. He added that the “good news” was that the country now had a diagnostics industry.

One life sciences industry executive suggested a failure to tap into private sector expertise was part of a far wider pattern evident during the pandemic in which ministers and officials had struggled initially to grasp the role business could play in tackling shortages.

PHE officials said that any offers of help from commercial labs were passed on to the health department which set up a formal process for handling the offers. Initially, under health and safety regulations, only high biosecurity labs had been permitted to use its test, the agency said, but it had “moved fast” to get these rules adjusted and expand the number of labs that could deploy it.

The prime minister has promised a public inquiry, which will undoubtedly scrutinise the role of PHE.

Mr Hancock’s comments this week suggested that he would not be pushing for immediate reform — but change will come. “There will be a time for that . . . We need a standing capacity, a public health agency not only brilliant at science but ready to go to mass scale very, very quickly.”

Lord Lansley, meanwhile, is clear that PHE cannot and does not operate independently from the health department. He added: “We will only discover in the fullness of time precisely what advice Public Health England gave and whether ministers actually followed it.”

Comments