Collector Yan Du on bridging east and west: ‘I am living my dream’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I see my project as a bridge between Asia and the west, as a platform for curators to study and share their knowledge,” says the Chinese art collector and patron Yan Du.

Many collectors sit on boards and acquisition committees as their way of supporting the art ecosystem. Du takes a different approach — she has started a foundation which supports emerging curators from Asia, while at the same time improving knowledge about Asian and specifically Chinese art in the west. Her Asymmetry Art Foundation has already established partnerships with London’s Chisenhale and Whitechapel galleries, and the aim is eventually to create a global exchange, sending western curators to China and vice versa.

Yet there is nothing in Du’s background that pointed to her becoming so involved with the art scene. She was born near Beijing, where her parents still live: “My family is very traditionally Chinese, and my father is a complete workaholic, like lots of Chinese businessmen, he doesn’t like to take holidays!” she tells me, laughing heartily.

We are talking over Zoom; she is sitting in her Hong Kong home, I in London. Behind her is an untitled portrait from 2003 by the American artist Laura Owens, and the choice is no accident: Du’s collecting is focused on work by women artists, although not exclusively so.

Du is direct, enthusiastic and energetic: she sometimes leans towards the screen, gesturing to make her points, and laughs often. She moved to Hong Kong nine years before, with her husband (“lucky me, another workaholic!” she jokes) who is in financial services; they also have a home in London. Her collection, which numbers more than 300 works now, is spread between these two homes, with some in storage in Switzerland. I ask her how she started collecting, about 13 years ago. “I studied at the Academy of Art and Design at Tsinghua University in Beijing,” she says: “But the courses were focused on Asian art.”

The big change came when she did an MBA at Queen Mary University in London, which opened her eyes to western art. “I felt, ‘Wow!’, here is another kind of art, it’s so different, more experimental, it shocked my brain!” she recalls. “I went to Tate, to art galleries and museums. London institutions are so intellectual, so inspirational!”

The first work she bought was by the Belgian abstractionist Raoul De Keyser, “Zacht Trio” (2009). “My education in traditional Chinese art helped me appreciate his sense of painting — it’s important to have a good grounding in the technique,” she says. “In the beginning I bought what I liked, but gradually I wanted a deeper relationship with art. I am still learning how to be a collector, even now. I don’t see myself as a ‘collector-collector’ but rather as a lover of art.”

After the birth of her two daughters, she became more aware that some of the works she had already acquired were by female artists, among them Louise Bourgeois, Mona Hatoum and Yu Hong. “My first major purchase was a Louise Bourgeois, before buying it I did a lot of research. I was really touched by her work, she is such a strong female figure, and she made me believe in supporting female artists.”

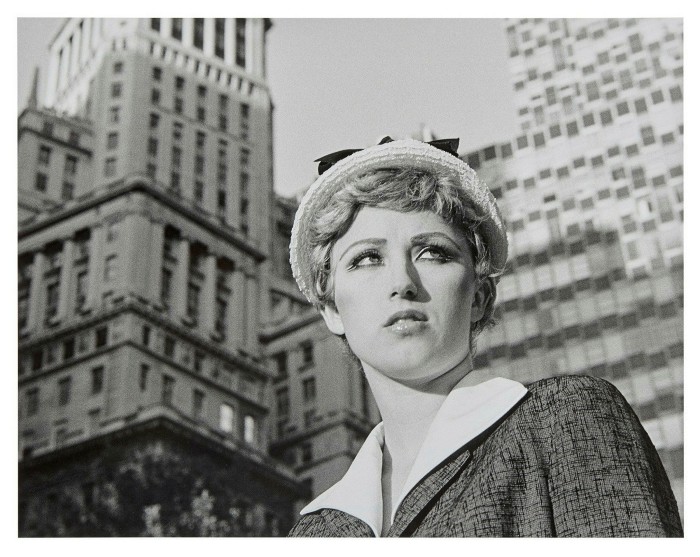

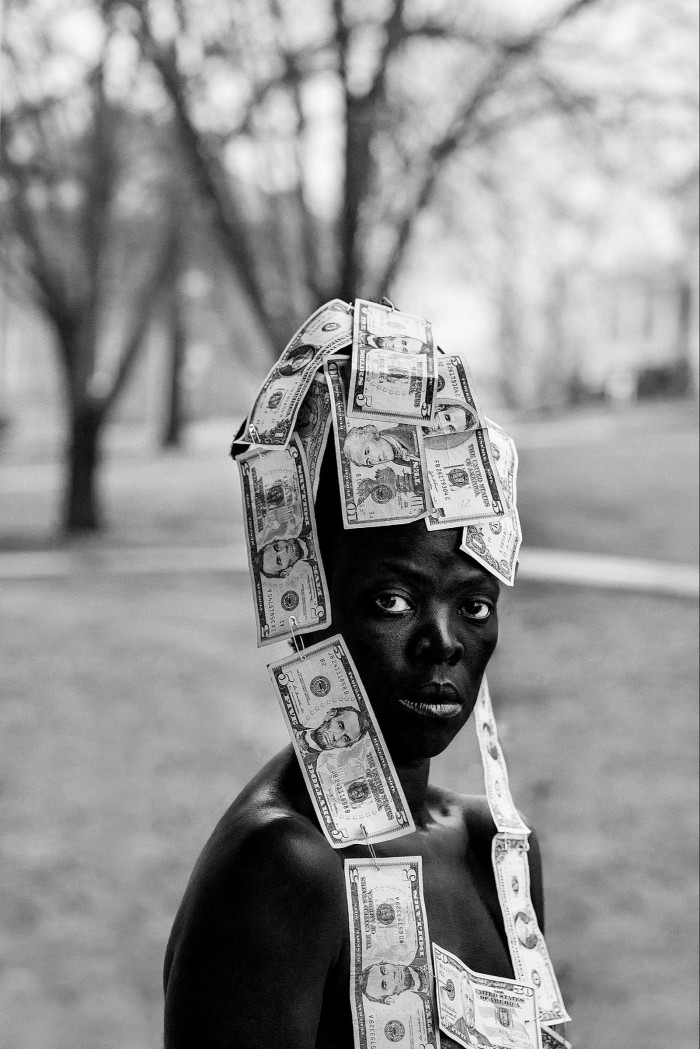

Now her collection comprises more than 150 artists, many of them women, including Sarah Lucas, Elizabeth Peyton, Diane Arbus, Joan Mitchell, Sophie Calle, Cindy Sherman, Rebecca Warren and Zanele Muholi. But she also has works by Thomas Demand, Danh Vo, Luc Tuymans and Pierre Huyghe.

In her holdings are also contemporary Chinese artists such as Cao Fei and Yu Hong, who she particularly appreciates being able to meet in person. “I am living this moment together with them; being able to talk to them makes me feel really involved. I can’t do that with Georgia O’Keeffe!” she smiles.

This sense of being involved in the art world is one of the great pleasures she gets from her foundation. She explains that her parents insisted that she further her studies in business: they hoped she might take over the family companies. Like many of her generation in China, she is an only child.

Now, she says, “I always regret that I didn’t study art history and curation, so now by creating this foundation, I am also able to acquire so much knowledge. Curators have such an important role in the art ecosystem, they are the ones who introduce artists to the world. Through the Asymmetry initiatives I am learning about all aspects of curation — about how to run an institution, how to budget shows, the logistics, aspects that people often forget.”

“I dreamt of learning all this when I was younger, but there was no possibility at the time, so this is giving me a second chance,” Du continues. “And now it’s a win-win situation — I am living my dream, and also giving the world something back.”

The foundation offers fellowships and scholarships to curators from Asia and greater China — which includes Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau. The first Asymmetry curatorial writing fellowship at Chisenhale has gone to Hang Li, a researcher and curator based in London and Beijing. In April a fully funded four-year PhD scholarship at Goldsmiths was awarded to Weitian Liu, whose subject is modes of knowledge production pertaining to contemporary art in Asia.

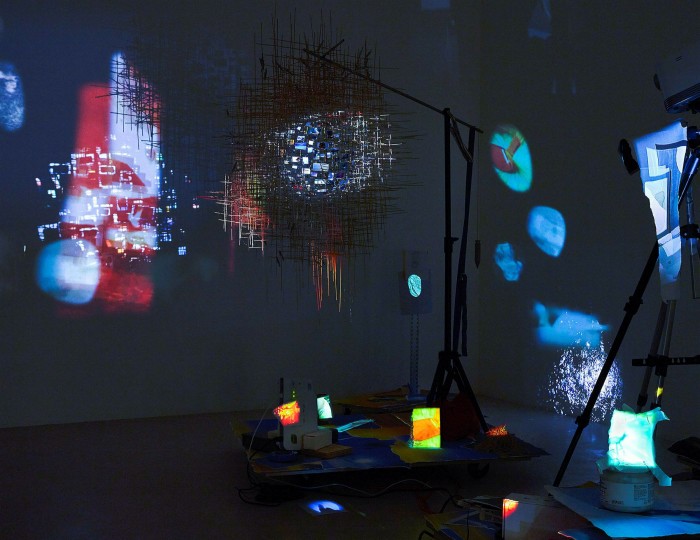

Du’s collection continues to grow, although the emphasis, she says, is on “quality not quantity”. Her latest acquisition is a 2020 installation by the American artist Sarah Sze, “Plein Air (Times Zero)”. I ask her if she wants to create a private museum with her collection, as so many wealthy Chinese people have done. Her answer is negative. “I don’t think so. I think there are other ways to display a collection than in your own space. But I don’t really know about the future — I am still processing that.”

As for the family companies: “My father used to think I would go back and take care of the companies. I tell him he should perhaps give them back to the country when he retires — and I say I’m sorry!” At the same time, she has obviously absorbed the lessons of business. “I like being direct and efficient . . . And I am proud of what I am building with my foundation.”

Comments