Mexico takes drastic measures to halt rise of ‘super-obesity’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Juan Pedro Franco, a 33-year-old Mexican, was so obese that no hospital had the facilities to see him. Bedridden for seven years, he reached a world record weight of nearly 600kg (1,320lbs).

Mr Franco suffered from diabetes, hypertension, lung problems and chronic swelling in his legs. He dropped 170kg simply to be able to undergo life-saving gastric surgery at a clinic in the western city of Guadalajara in May that had to widen its entrance and bring in stronger beds just to receive him.

He was a case of “super-obesity — off all the charts,” according to his surgeon José Antonio Castañeda, who sees an average of eight patients, mostly women, every day. “It’s a huge number, so you can see the scale of the problem in Mexico,” he says. Not all of those prospective patients are candidates for surgery but Dr Castañeda nonetheless performs 40 procedures a week.

Mexico is suffering an obesity epidemic that has helped diabetes become the country’s number one killer. One in three Mexican adults and three out of 10 children are obese or overweight; one in four adults suffers from hypertension; and nearly one adult in 10 has been diagnosed with diabetes. Before Mr Franco, two other Mexicans held the record for the world’s fattest person. Both died.

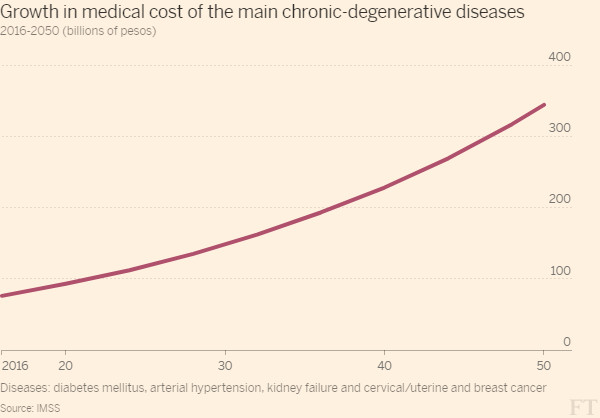

According to state health insurer IMSS, which covers some 19m Mexicans and runs more than 6,000 medical centres, diabetes, hypertension, kidney failure and cancer have become the biggest causes of death. Combined, they gobble up a third of the agency’s budget. IMSS estimates that the cost of treating them will soar more than 4.5 times by 2050 to 344bn pesos ($18.4bn) a year from 76bn pesos now. “There’s no money for that,” says IMSS chief Mikel Arriola.

That has prompted a seismic shift within IMSS to a new model of preventive care, launched on May 4, in the northern state of Nuevo León. Mr Arriola expects to roll it out widely next year.

Instead of treating patients when symptoms arise, the new approach is to identify those at risk and nip disease in the bud by having IMSS doctors visit companies and perform health checks on workers. So far, 10,000 out of a target of 127,000 people have been seen — and 20 per cent have been found to be pre-diabetic, with higher than normal blood sugar levels, without knowing it.

In blunt financial terms, “it is not the same treating a diabetic with insulin — which costs 230 pesos a year — as a [more advanced] diabetic needing haemodialysis at a cost of 230,000 pesos,” Mr Arriola says.

The government has been running a campaign encouraging Mexicans to go for check-ups, eat healthily and exercise more, while in 2014 it introduced a one peso per litre soda tax. The tax raised 70.6bn pesos from January 2014 to April this year, according to the finance ministry.

There has been some debate over how effective the reform has been, but a study by Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill this year that found sales of sodas were 7.6 per cent lower than would have been expected based on trends before the tax was introduced.

However, Anprac, the national association of soda producers, and ConMexico, a group of leading food and drinks industries, concluded in February that if the tax take went up, "so did consumption”.

A push to double the soda tax has so far come to nothing but a new study published by the Public Library of Science this month said that 10 per cent of calories in Mexico came from sugary drinks. It estimated the current tax would reduce obesity by 2.5 per cent by 2024, preventing between 86,000 and 134,000 new cases of diabetes by 2030.

Yet two-thirds of the population considered that they ate healthily and were physically active in a national health survey published last year. As Dr Castañeda put it: “In the last four years, in spite of certain strategies . . . the problem is still rising.”

The answer, according to Benjamín Villaseñor, is technology.

A geneticist by training, Mr Villaseñor set up Uhma Salud to use diagnostic algorithms to make detecting health problems cheap, scaleable and easy to follow up.

One drop of blood, one bar code, one set of scales, one tape measure and five minutes is all it takes for Uhma Salud to track glucose levels, cholesterol, triglycerides, heart, blood pressure, weight, height and body composition. “With this, you can detect conditions that cause 80 per cent of the mortality in this country,” Dr Villaseñor says.

Uhma — launched in 2009, has raised $2m and hopes to go public within five years — can pack its diagnostic equipment into a rucksack. It visits companies nationwide, including baker Bimbo and sodamaker PepsiCo, and tailors wellness portals and programmes for insurance companies to offer their clients.

Ultimately, as well being good for workers, improving staff health is good for business, campaigners say.

Some companies using Uhma tools have made employee health a performance metric, or introduced yoga or health coaching at work. “People taking part lost 4kg on average,” says Roberto González, finance director at Uhma. “All that lost fat is productivity.”

Comments