Max Richter – musician of the moment

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ahead of the FT Weekend Festival on 4 September at Kenwood House in London, we’re republishing our July interview with Max Richter, who will be speaking to Nicola Moulton in the How To Spend It tent at the event; ftweekendfestival.com

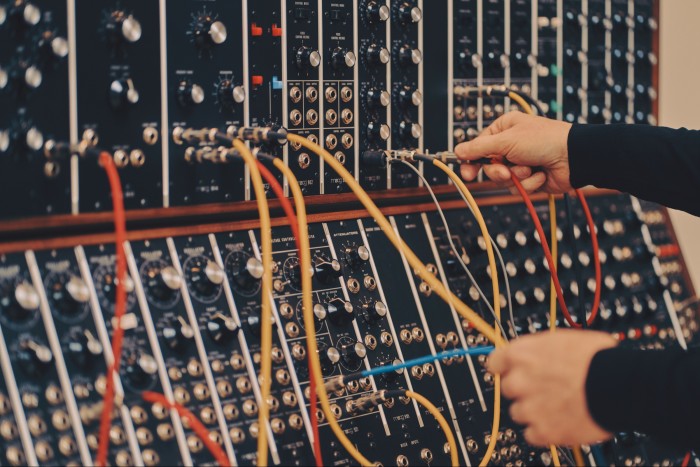

When the composer Max Richter was 13, he got hold of a soldering iron and built his first synthesiser out of electrical components. He had fallen in love with electronic music after hearing the German electro-music pioneers Kraftwerk, and his passion for inventing new sounds grew alongside his prowess at the classical piano.

This blend of the classical and modern, electric and acoustic, is a hallmark of Richter’s beguilingly genre-defying music, which is sometimes orchestral, sometimes digital and most often a marriage of the two. His post-minimalist sound draws as much from composers like John Cage and Steve Reich as it does from the punk bands he listened to as a teenager.

Intense, haunting, exhilarating, provocative – it often feels as if he is part-composer, part-inventor. Given that he can lay claim to being the world’s most-streamed “classical” composer, you will almost certainly have heard his work: Richter has written music for more than 50 film and TV projects, including HBO’s My Brilliant Friend, Tom Hardy’s Taboo and Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror. Fans of Bridgerton will be familiar with one of his best-known works, “Vivaldi Recomposed”, which he described as “throwing molecules of the original Vivaldi into a test tube with a bunch of other things, and waiting for an explosion”. But perhaps his most famous composition is Sleep, an “eight-hour lullaby” released in 2015 intended to accompany a full night of restfulness and which, as of July 2020, had amassed close to 500m streams. Currently, he must surely be noted as the favoured composer of those working from home.

Richter was born in Hamelin, north-west Germany, but grew up in Bedford. He has described himself as a “cripplingly shy” child and was obsessive about music and books. He went on to study piano and composition at the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Academy of Music, completing his studies with the experimental composer and electronic pioneer Luciano Berio in Florence. For a time he earned a living as a pianist, and collaborated with British electronic group The Future Sound of London and the DJ Roni Size.

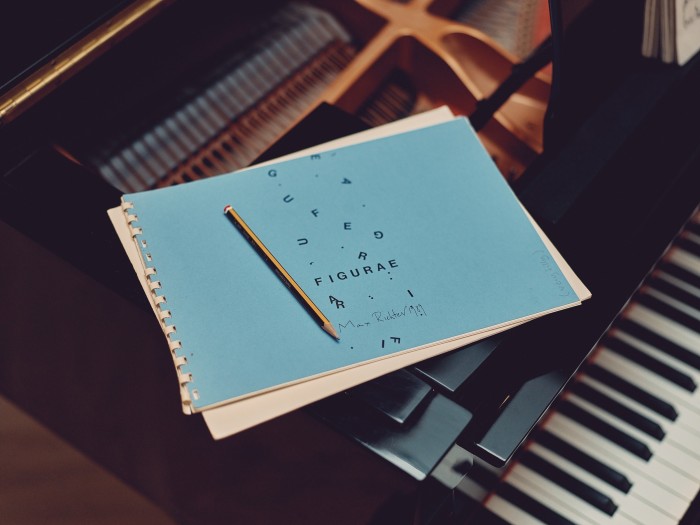

And here, 30 years later, he is still very much spanning the musical spectrum. Within the new studio he and his artist partner Yulia Mahr have built deep in the Oxfordshire countryside, his huge, light-filled workspace has a Yamaha grand piano at one end and an Apple computer and Moog System 55 synthesiser at the other. “We can do any sort of recording here,” he says of the studio, an expansive old barn that was once part of an alpaca farm. The original structure is now divided into separate rooms for both Richter and Mahr. Her airy studio sits across the front of the building, while the rest of the space is filled by a recording room, which can comfortably seat an orchestra of 30, and Richter’s own domain, a huge, vaulted room, the exact dimensions for which he took from the loft he worked in when he, Mahr and their three children lived in Berlin.

“Obviously we’ve got the computers and the digital side, but we also have new machines so we can record to tape, which is super-important to me because I love the sound of analogue media,” he says. “We can do something very retro here but we can also do a Dolby cinema mix, too – so we can span both ends.”

This breadth is doubly important given the sheer range of Richter’s work. Early on in his career, he took commercial work as a way of funding his solo projects, but that pluralistic approach has led to a career in which he is now as acclaimed for his soundtracks and ballet scores as he is for his own more personal work. In the past year, he reworked some of the music from his 2015 ballet Woolf Works for Kim Jones’s Fendi spring/summer 2021 couture show and released Voices 2, a companion to the earlier work Voices, which premiered just before lockdown and which takes as its centrepiece the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He crowdsourced readings of the text on social media and received hundreds of submissions in more than 70 languages, weaving the music through his chosen excerpts.

“I see the Declaration as all about potential,” he says. “It would be wonderful to play it in front of audiences some more, because that text is so important at this moment where global societies and cultures are thinking about what the next step is, and there have been all kinds of power grabs in the area of rights. I just feel like I want it to be heard as much as possible, because it’s just a great way to shine a light on those questions.” In fact, its first post-lockdown airing is already scheduled: the Max Richter ensemble will perform it at the South Facing Festival in London’s Crystal Palace Bowl on 28 August. Richter feels it will be an incredible moment: “Music is all about communication and for musicians not to be able to do that… it’s like we really thirst for it. Performance is like a ‘real-time’ laboratory; it’s where you find out what you’ve made. The pandemic has been a disaster for the venues and institutions, the bands, the orchestras. I mean, it’s been decimated. The government is going to have to step in more. Whole orchestras of musicians are retraining to do other things.”

Richter talks quietly, thoughtfully, and in a way that, like his music, shifts seamlessly from the personal to the political. He says that the idea for a kind of rural studio-retreat – or, as he and Mahr sometimes refer to it, an “art farm” – has been percolating for 20 years. They are united by their belief in the power of creativity to influence societal change – and Richter is driven by an unequivocal belief that music can help us navigate the big, difficult questions that we face as societies by providing “a place to think and reflect”. Being able to transpose that idea into a physical space, one which comes with an atmosphere of both calm and creativity, has long felt to them both like an important project. “I guess both Yulia and I share an idea of how creativity and culture can fit into society, and what it can do within society,” says Richter. “And that’s to do with connecting people, and allowing people to ‘speak’ to one another in this different medium – which needs a place where that can happen.”

By any standards it’s an impressive building, with floor-to-ceiling windows giving views straight into the surrounding forest. But compared to the setup of most modern recording studios it’s practically cathedral-like. Recording studios are often the least glamorous part of the musical process: windowless, airless rooms dedicated to the sound, not the person making it. “The thing that a lot of studios do is they build a machine, and you feel like you’re inside a machine when you’re in there, which in a way also disregards the fact that you have a body. So trying to make spaces for musicians that are humane, and inviting, and comfortable, I think is really important,” says Richter.

Aside from it being a base where Richter can both compose and record, the idea is to make the studio available to others; particularly emerging artists and young musicians struggling to afford a studio, or even a place in which to experiment and create. “With studio time, you’re always on the clock,” says Richter. “And having that pressure can sometimes be quite stifling. We have space, and we have great facilities. We’re exploring ways to put together a programme so that people have access to all of this.” Alongside the studio, Richter and Mahr have had huts built in the woods so that visitors can stay for a few days at a time – and eventually there will also be a café to feed the creative team and visiting artists, too.

A transient hub, with artists and musicians coming and going, allows for the kind of creative serendipity that benefits everyone, says Richter. “Obviously I’m doing my work here… and I love the idea that one day there’ll be some kind of mega Hollywood film project, and the next there’ll be a bunch of kids trying something. I love the idea of these things being within proximity… because that sort of constellation can be so rich.”

Beyond offering the practical support of world‑class recording facilities, Richter is optimistic that the space may also open up ideological discussions about what music can contribute in the wider world. In his solo work, he describes himself as a “composer and activist”, and his music has responded to the Iraq war (The Blue Notebooks features actress Tilda Swinton reading excerpts from Kafka’s The Blue Octavo Notebooks) and the London bombings of 2005 (Infra, inspired by TS Eliot’s The Waste Land).

His new album Exiles, released in August, continues this exploration. The album’s title work comes from a ballet commissioned by Paul Lightfoot and Sol León (resident choreographers of Dutch contemporary dance company Nederlands Dans Theater) in 2014 – the moment when the Syrian refugee crisis exploded in Europe, and debates became particularly polarised in Germany, where Richter was then living. “I think creativity is really about finding those things that you want to communicate, that you want to talk about,” he says. “I think ultimately that’s what we’re all trying to do; to figure stuff out by making things. So a place like this, because it’s sort of wide-open in a way, it becomes sort of a big question mark for somebody to walk into. And we just press ‘record’ and see what happens.”

What he most wants to do, he says, is allow emerging artists to realise they don’t necessarily just need to “pick a lane” and stick to it, but should be able to pursue different avenues creatively. “Streaming has meant that people listen really widely, because there isn’t any risk. You don’t have to spend 20 quid on the record or even go to the record shop – you just click and there you are; you’re hearing something you probably wouldn’t otherwise have heard. That’s made a music culture that is very plural, and the categories are quite fluid now, which I think is really interesting.”

Max facts: the composer’s most-streamed tracks

ON THE NATURE OF DAYLIGHT

From The Blue Notebooks (2004) 211m

VLADIMIR’S BLUES

From The Blue Notebooks (2004) 155m

DREAM 1

From Sleep (2015) 120m

SPRING 1

From Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi, The Four Seasons (2012) 82m

A CATALOGUE OF AFTERNOONS

New track on the 15-year anniversary reissue of The Blue Notebooks (2018) 71m

Although he embraces technology so freely in his own work, Richter is also aware of the paradox that much of his music also seeks to find solace from the digital onslaught – nowhere more so than in Sleep, which has been staged around the world as an overnight performance, with the audience listening in camp-beds rather than chairs.

FT Weekend Festival

Max Richter will be speaking and performing at the FT Weekend Festival on September 4. To book tickets for the festival, visit here

Throughout Covid, Sleep has taken on a life of its own and there’s now an app that allows you to set sleep, meditation or focus schedules to Richter’s music. When the idea of the Sleep app was first put to him, he wasn’t sure it was a good idea, but now he sees it as an example of how technology can be a positive. “When I saw it I just thought, ‘Wow, this is what the iPhone was invented for’,” he says.

“I think that idea of technology as this kind of double-edged sword is becoming more acute,” says Richter. “I mean it’s a tremendous enabler, of course… when I was a kid, if you wanted to write for orchestra, you had to go to university and learn how to do it, then persuade a bunch of people to sit down and play your stuff. Whereas now, if you want to write for orchestra, you can on your laptop make the sound of an orchestra… kind of. But on the other hand, technology is obviously deeply embedded in the kind of late-capitalist, neoliberal model – it’s a symptom and a cause of that, and it’s also what’s putting us all in the hamster wheel. We’re just learning how to deal with this stuff. It’s going to take some time.”

For Richter, technology needs the antidote of nature to provide the balance that will temper us creatively. It’s why the studio could never have been built in a city. “I think there’s a big thing about just being here, in nature,” he says. “It’s really a ‘headspace’ thing. People can come, hang out for a few days, do some work – but they’re in the forest. And I think that’s great. I just love that sort of balance. I suppose, if we think of the past year or so as a big question mark, then potentially, now, there is an opportunity to create some positive answers.”

Comments