Diabetes risk: what’s driving the global rise in obesity rates?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The number of adults living with diabetes has reached an estimated 463m — equivalent to 9.3 per cent of the world’s adult population, and four times higher than the number of cases recorded four decades previously.

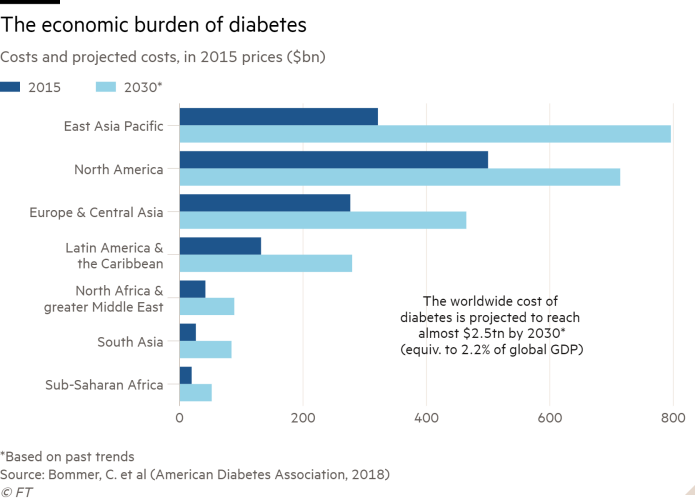

The cost to the global economy is immense: upwards of $1.3tn, and rising. By 2045, the number of adult diabetes cases is expected to reach 700m.

Behind this alarming increase lies a surge in obesity, which now affects nearly one-third of the global population. According to the charity Diabetes UK, obesity accounts for 80-85 per cent of the risk of developing type-2 diabetes.

But what lies behind the rise in obesity? For a long time it has been attributed to mass migration into cities, where lifestyles are supposedly more sedentary and unhealthy food is more plentiful.

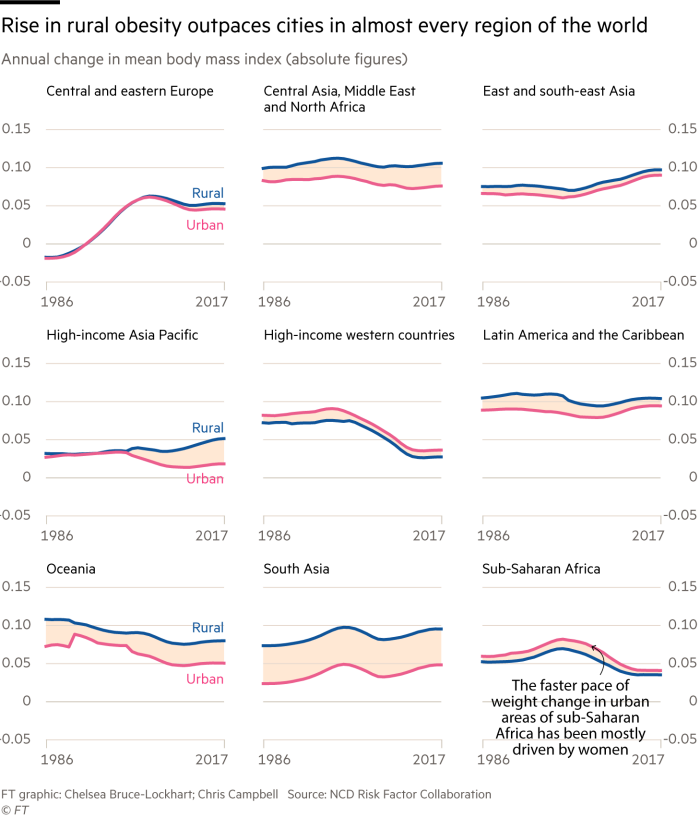

Yet according to a study led by scientist network NCD RisC, the “urbanisation of rural life” has played a much larger role.

It concludes that more than 55 per cent of the rise in adults’ weight over the past three decades has been driven by rural populations taking on habits more traditionally linked to urban-living. Just 13.5 per cent of the rise was caused by urbanisation.

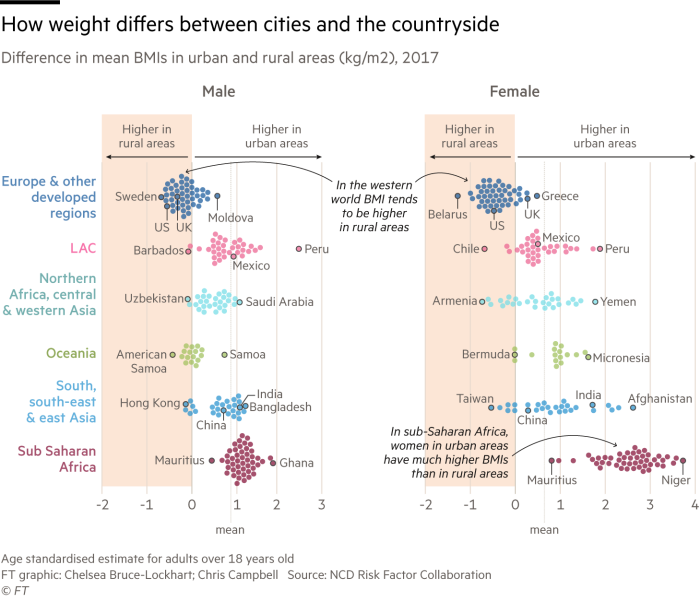

In most areas of the world city dwellers are still more overweight than those living in rural areas. But the gap is narrowing.

Living in rural areas once meant expending lots of energy on agricultural activities and daily household tasks such as collecting water and firewood. At the same time, lower incomes restricted food consumption.

Podcast: How to Build a Healthy City

FT correspondents unearth the ways cities are helping their citizens live healthier lives, from doctors who prescribe exercise rather than pills, to a car-free economy that is booming. Listen to the series

Now, though, rural diets have changed. “Cheap, calorie-dense, unhealthy, refined foods have better distribution than in the past. It’s got to more corners of the world than it used to,” says Edward Gregg, a professor at Imperial College London’s School of Public Health.

Meanwhile, increased mechanisation on farms has encouraged more sedentary behaviour. “[In the US] we've automated our rural agriculture to the point where energy expenditures aren't that much higher [than in] urban service sectors,” says Barry Popkin, distinguished professor at the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health.

There is widening consensus that these two factors are creating unhealthy lifestyles in rural areas, increasing the prevalence of obesity and the risk of developing diabetes.

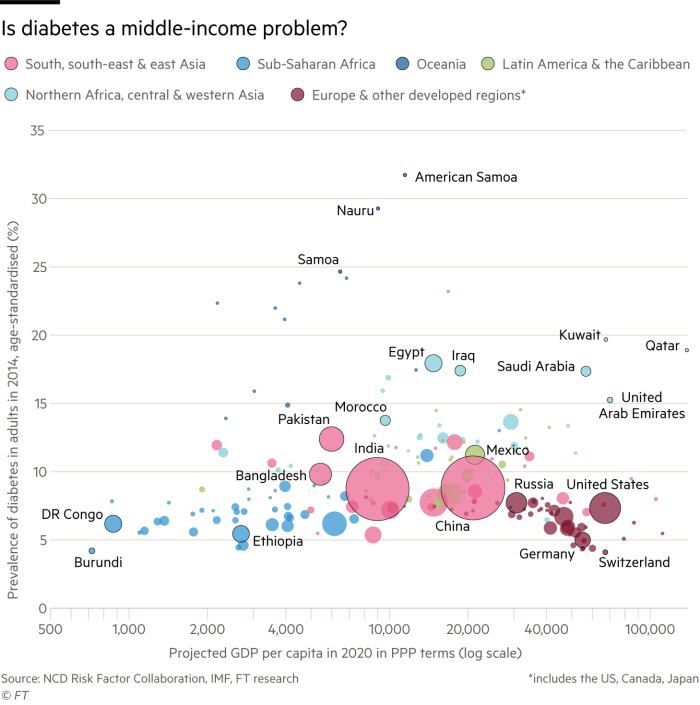

Of particular concern are some of the most populous middle-income countries, where rapid rises in obesity are now being seen across the entire population, both inside and outside cities.

“It’s worrying how rapidly this seems to be occurring in [countries such as] China, India and Mexico. They are really the epicentres for this problem,” says Prof Gregg.

In China, for example, the share of people considered overweight or obese increased from 15.8 per cent in 1991 to 36.8 per cent in 2015, according to the China Health and Nutrition Survey. The difference between China’s urban and rural obesity rates also became negligible over this period.

At the last count, the survey found that, for both city- and rural-dwellers in China, more than one in three were overweight or obese compared with a markedly different 23.5 per cent and 12.8 per cent respectively in 1991.

East Asia Pacific is the region set to bear the biggest cost burden from diabetes. Based on past trends in prevalence rates, the global economic costs — which factor in anticipated healthcare expenses as well as the loss of earnings and productivity — could rise to as much as $2.5tn by 2030, according to research published in the journal Diabetes Care. In the east Asia Pacific region alone, these costs will be as high as $796bn.

“The idea is to avoid complications because that is the costliest component in terms of healthcare and expenditure and in terms of productivity loss,” says Gojka Roglic, medical officer from the World Health Organisation’s department of non-communicable diseases.

The longer a person lives with undiagnosed and untreated diabetes, the worse their health outcomes are likely to be; they will be more likely to suffer from blindness, kidney failure, heart attacks or stroke. Symptomatic foot ulcers and infections can lead to an eventual need for limb amputation.

“[Diabetes] doesn’t kill you as quickly as it debilitates you,” Prof Popkin explains. “From an economic perspective, productivity in rural areas is going to suffer from this.”

As weight gain continues to increase in every region of the world, both inside and outside cities, the strain on the global healthcare system is set to rise.

“My fear is that the change in rural areas is even worse, since they have less access to medical care. And it's more untreated,” says Prof Gregg.

Comments