Is ‘buy now pay later’ a viable business model?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Those of you who keep an eye on what’s happening in fintech will know that, outside of the fantastical land of crypto and non-fungible delights, the hottest game in town right now is “buy now pay later” — or BNPL as it is widely known (best pronounced as buh-n-pul).

The market has, until now, been dominated by BNPL pioneers like Sweden’s Klarna — Europe’s heftiest fintech unicorn at a valuation of over $45bn — and Australia’s AfterPay, which in August was acquired by Jack Dorsey’s Square for a tidy $29bn, the largest takeover in the Land Down Under’s history.

But ever more firms are now jostling for a taste of that sweet BNPL sundae. Just last week, old-man “fintech” Mastercard said it would launch a product called “Mastercard Installments” next year. Apple and Goldman Sachs have said they are joining forces to offer a service called “Apple Pay Later”, while BNPL big dog Affirm recently announced a partnership with Amazon that will allow US customers to split the cost of any purchases over $50, and PayPal launched its own version of the product last year.

In the UK, Revolut has said you’ll soon be able to switch on a button and “your card becomes a buy now pay later product”; Monzo recently announced a similar service — “Monzo Flex”. You get the picture.

Clearly, BNPL is growing rapidly — its use trebled in the UK during 2020 — and it is doing so from a low base: it still only represents about 2 per cent of the ecommerce market globally, and about 1 per cent of Britain’s credit market. So there is plenty of room to grow. But does it constitute a sustainable business model on its own?

Redburn, the UK equity research house partly owned by Rothschild, doesn’t think so. Last week they published a report in which its analysts deduced that “BNPL as a standalone business is not viable”. With such a punchy top line, we thought it was only fair to share some charts and nuggets from the note.

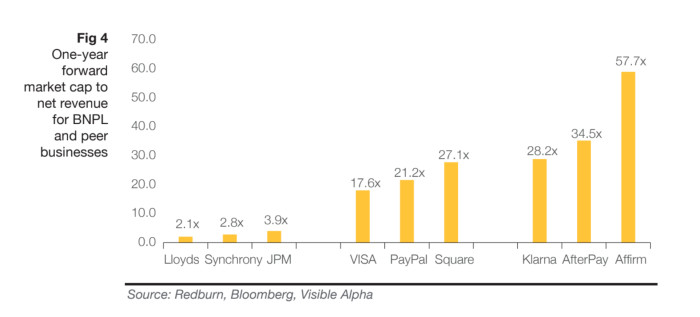

First, investors are clearly taking notice of these firms. Take a look at this chart showing how the valuations of standalone BNPL companies stack up with those of traditional lenders (ie banks), and even payments companies that are themselves getting into the market:

As you can see on the chart, while the valuations of vanilla lenders range from between about 2 to 4 times forward revenue, the multiples commanded by BNPL firms’ valuations are as high as 58 times.

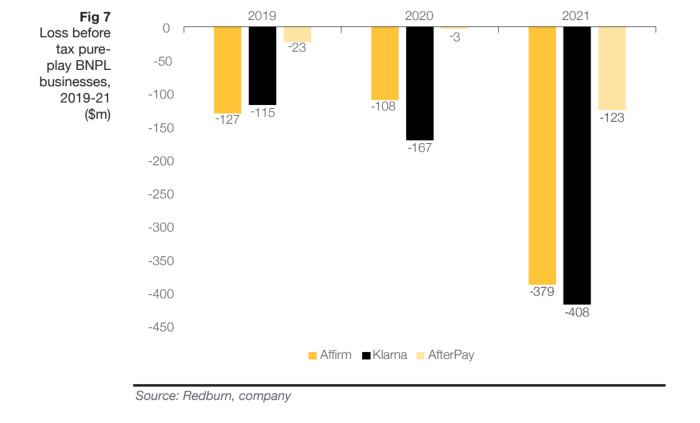

And that’s despite none of these companies actually making money. Having been profitable for its first 14 years in business — a considerable achievement in fintechland — Klarna went into the red in 2019, and has gone deeper into it since. In fact none of the big three standalone BNPL firms are currently making a profit:

So what is the appeal of BNPL in the first place? According to Redburn, the key thing, like much of the rest of the tech world, is customer acquisition. But customer acquisition is all very well if you have other products that you can direct your newly acquired customers on to; it’s less good if you don’t:

What BNPL does offer is an excellent route for accelerating customer acquisition, which businesses with a wide array of products can monetise through bundled payment pricing. As such, companies like PayPal and Square are well placed. However, for pure-play BNPL players, the option is to evolve, be acquired or end up disappointing on long-term profitability.

One the key reasons BNPL has been able to grow so rapidly, and the reason valuations are so high, is the sector is very lightly regulated. But that is likely to change, says Redburn, particularly when the credit cycle eventually turns:

A credit event will not only result in losses but . . . probably in a material amplification of pressure from governments and regulators. At the very least, the credit checks required by banks when making loans could be bought in to the BNPL sector, slowing the customer acquisition enticed by its current minimal checks.

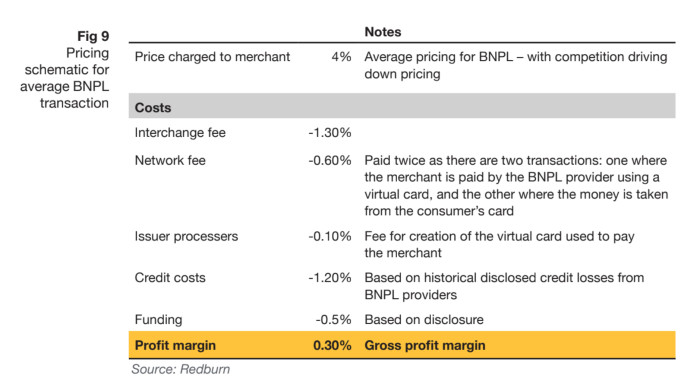

The lack of regulation so far has helped BNPL firms grow rapidly and keep costs down; when tougher rules are brought in, profit margins will be squeezed. Here’s a chart showing a typical pricing structure, assuming the retailer pays 4 per cent to the BNPL vendor:

As Redburn points out, a 30-basis-point gross profit margin is similar to non-BNPL payments companies. But these companies aren’t taking the same kinds of risks:

Once we factor in interchange, network fees, issuer processing fee, credit losses and funding, there is little left for the BNPL provider . . . The 30bp margin in and of itself, with a scalable business, can be lucrative. Adyen, for example, makes c20-30bp per dollar processed and has an EBITDA margin north of 60% owing to the scalability of its platform. A critical point, however, when considering the relative investment case, is that Adyen makes a similar margin to a BNPL without assuming a material credit or funding risk.

Redburn concludes that in order for BNPL businesses to stand a chance of surviving, they will either have to be bought up by a bigger player that can use the service as to cross-sell other products, or the companies themselves will have to start offering other services.

The latter is what Klarna is doing. Redburn again:

We hosted Klarna at our FinTech conference in June 2021 and it was clear its plan was to move towards the ‘super-app’ model. Its revenue stream is already diverse, with affiliate revenues from merchants running at a 400-1,000bp margin. If BNPL can increase affiliate revenues, this offers a path to monetisation away from pure-play BNPL. The end goal is to become an ecommerce platform with payments at the heart of its monetisation model. BNPL was a stepping-stone to acquiring customers, something it has done spectacularly.

But even if these BNPL companies do evolve in this way, however, we still have doubts — we don’t see a clear path to profitability for fintech super-apps in countries that already have developed financial systems and high levels of financial inclusion too, as we have expressed here a few times before.

Redburn concludes that:

While BNPL is currently the talk of the town, ultimately it is simply a tool to attract new customers on to new forms of payment, and to continue the move towards a world in which digital wallets reign and the costs are transferred from the consumer to the merchant.

Klarna CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski said in August that the company might consider an IPO as early as 2022. We are sure it will be popular. But for investors, it might end up being a case of buy now, regret later.

Comments