The beautifully turned world of Lucie Rie

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

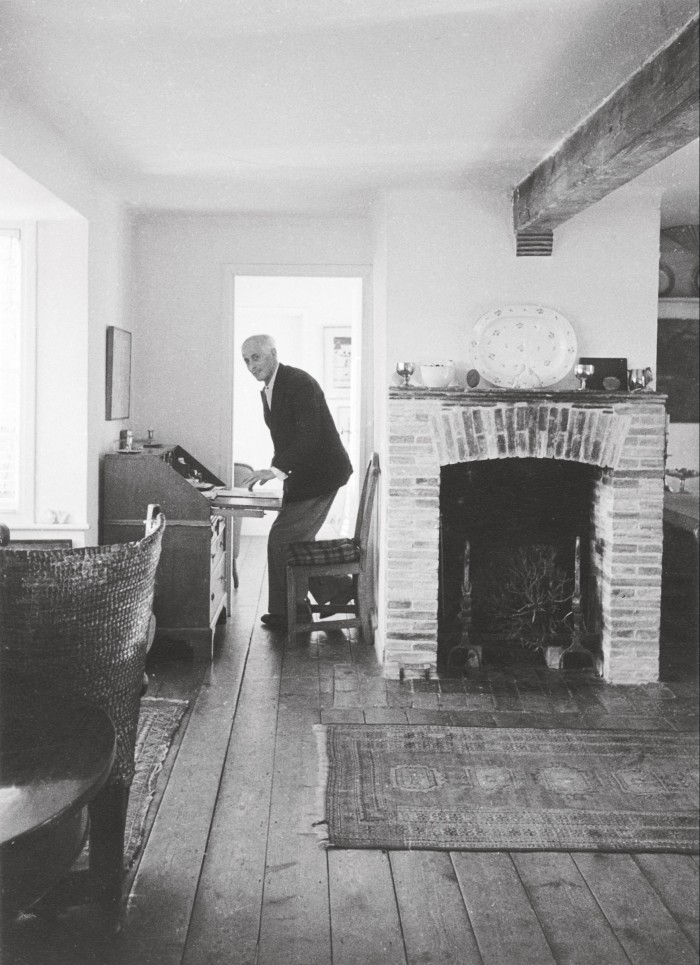

One of the most memorable ensembles among the collection of British modern art, natural finds and artefacts on display at Kettle’s Yard – the former Cambridge home and gallery of the late collector Jim Ede and his wife Helen – is in the far corner of the modern extension to the original quartet of 19th-century cottages. Here, on a slate-topped table, a glass goblet arrayed with twigs sits alongside a marble-and-string “Fiddle Fish” forged by little-known artist John Clegg, and a pair of glass fishing floats. Notably, this eclectic assemblage of high and low art and objects also casually includes an ethereal white bowl by Lucie Rie, the artist born in Vienna in 1902 who has become one of the most celebrated ceramicists of the past century.

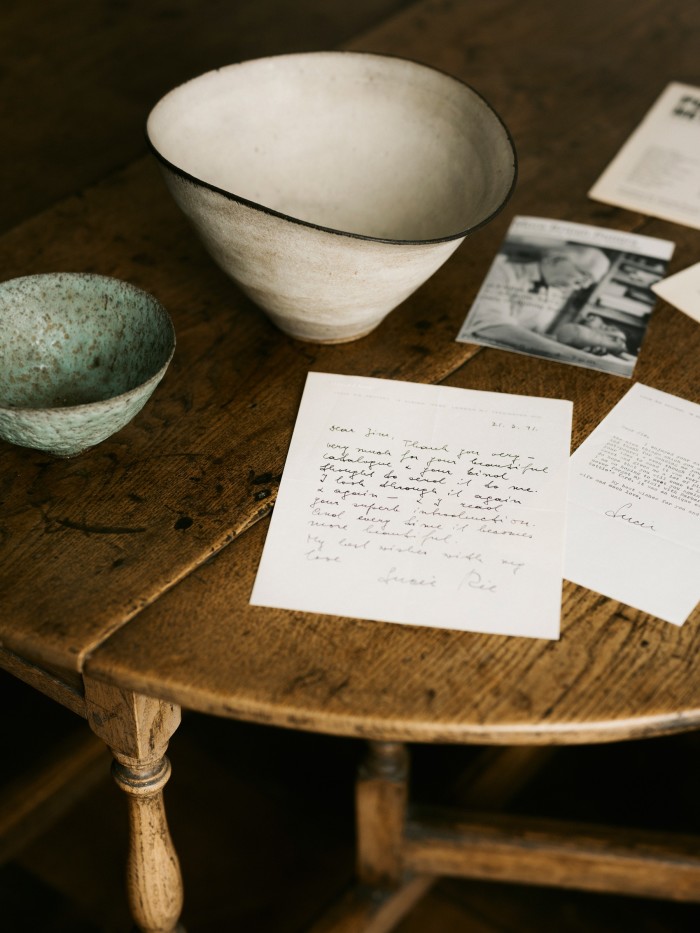

Remarkable in its restraint, elegance and purity, Ede christened the vessel The Wave for its undulating form. By the time it arrived at Kettle’s Yard in the early ’70s it had already been sold. But, the story goes, that didn’t stop an enamoured Ede from carefully carrying the bowl from the gallery’s exhibition space and into the house each evening to place on his slate altar where, with it basked in light, he could gaze at it in a sort of aesthetic reverie before dutifully returning it the next day.

That container, which eventually found its way into Ede’s hands, is now one of a series of Rie’s works to be prominently positioned throughout the Kettle’s Yard house as part of the permanent collection. Offering a rare chance to engage with her ceramics in a domestic setting, they highlight Ede’s sensitivity to the power of placement; that communion between objects which sees one thing speak to, and amplify, another.

“It feels as though there are invisible lay lines running between them,” says Kettle’s Yard’s director Andrew Nairne of the Rie pieces in the collection. So the earthy matte finish of a manganese bowl highlights the bleak beauty of a neighbouring black-and-white lake landscape by LS Lowry; and the silhouette of a sgraffito-lined porcelain bowl – whose technique was inspired by the bronze-age vessels Rie encountered on a trip to Avebury in Wiltshire – is accentuated by the pitted surface of a fossilised shell. We take this kind of thoughtful, wide-ranging and naturalistic curation for granted today, but when the Edes first opened Kettle’s Yard in 1957, after restoring and renovating the cottages with the help of architect Rowland de Winton Aldridge, the idea of “a living place where works of art could be enjoyed” by Cambridge University students and the wider public broke new ground. Dispensing with the formality of the traditional museum, the house became a radical artwork in and of itself.

Half a century after The Wave arrived at Kettle’s Yard gallery, a solo exhibition of Rie’s work opens there: Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery will showcase the dazzling breadth of Rie’s practice. More than 100 works forged across six decades range from a rare 1936 tea set to more than 170 ceramic wartime buttons loaned from a Japanese collector, and the superlative, single-fired and raw-glazed vessels she continued to make until her death in the mid-’90s at the age of 93. “To make pottery is an adventure to me,” she said. “Every new work is a new beginning.”

Today, Rie’s work is reaching record values at auction: in March last year, a large terracotta-footed porcelain bowl with a gold manganese glaze sold for £201,600 at Sotheby’s in London, exceeding its estimate eightfold, while a similar footed white vessel with an inlaid grid and sgraffito interior achieved $340,200 in New York in 2021. Notable collectors include Edmund de Waal, David Attenborough, Nigel Slater and the fashion designer Jonathan Anderson, and galleries including Primavera Gallery, Oxford Ceramics and Joanna Bird deal in her work. “Although she has always been appreciated and seen as important, there was a time when Rie was viewed simply as a ceramicist. Only now is she being appreciated more fully as an artist,” says Sofia Sayn-Wittgenstein, senior design specialist at Phillips.

It is particularly fitting that Rie should be returning to Kettle’s Yard, a place with which she shared a real synergy. After visiting in 1976, she wrote to Ede, “I shall never forget my visit”, calling it “a unique experience”. For Nairne, the worlds of Ede and Rie are simpatico. Beyond a joint taste for Windsor chairs, foraged rocks, flowers and semi-precious stones (Rie, he says, would have totally got the spiral of 76 stones arranged on Ede’s bedside table), lies a belief that art should be a “way of life”. This concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art”, sat at the core of the modernist movements that formed the backdrop to Rie’s early creative life.

Rie’s home in Vienna, painstakingly designed in walnut by Ernst Plischke in 1928, melded the same exalted sense of calm and craftsmanship as Kettle’s Yard. In 1938, Rie was forced to flee her homeland during the annexation of Austria by the German Reich. When she eventually settled at Albion Mews, London – a one-bedroom flat above a garage close to Hyde Park that became her studio – she had the Plischke apartment shipped over and reconstructed (it now sits in the permanent collection at the Vienna Furniture Museum). This space became a sanctuary, a place of respite from the warring world, where Rie famously served coffee and cake to would-be collectors surrounded by towering shelves of pots.

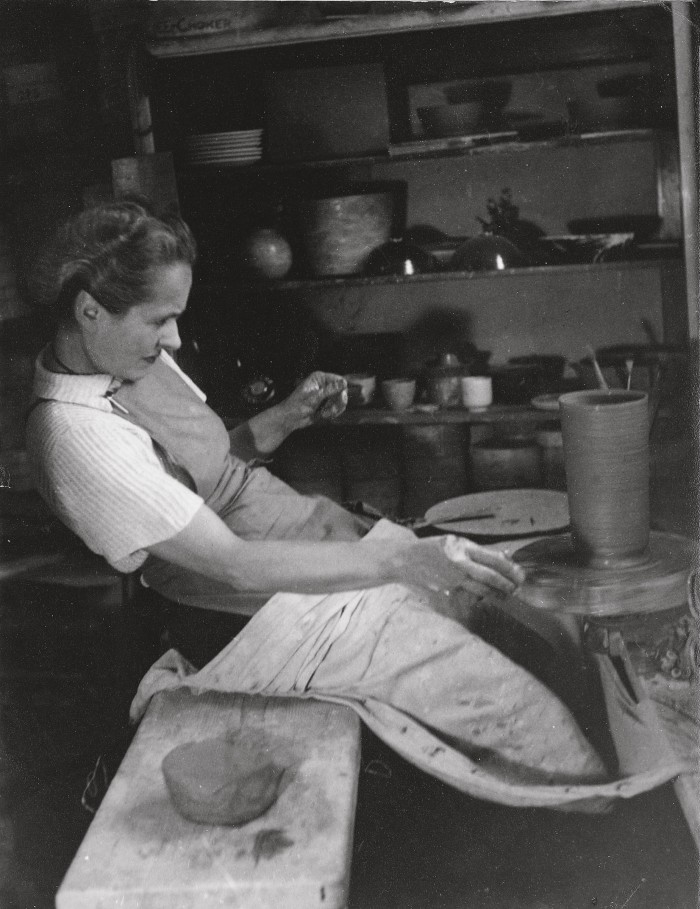

“Rie wanted to create a place of safety,” says design historian Tanya Harrod, a contributor to the exhibition’s accompanying book. “It was an extraordinary environment – very pure, and inhabited by this beautiful, immaculately dressed and seemingly austere woman.” While other studio potters obsessed over building kilns or making their own clay, Rie, nicknamed “the urban potter”, carved her own path, tirelessly making novel work in an electric kiln.

Although Ede was forever drawn to Rie’s simplest, most pared-back creations, what Eliza Spindel, a curator of the new exhibition, hopes to spotlight is the revolutionary nature of her work. “While the pieces that Ede collected share the same sense of stillness and equilibrium you’d use to describe Kettle’s Yard, the show also reveals her wildly experimental side.” It includes the early ’60s Jasperware prototypes she created for Wedgwood, which turned out to be too tricky to mass-produce.

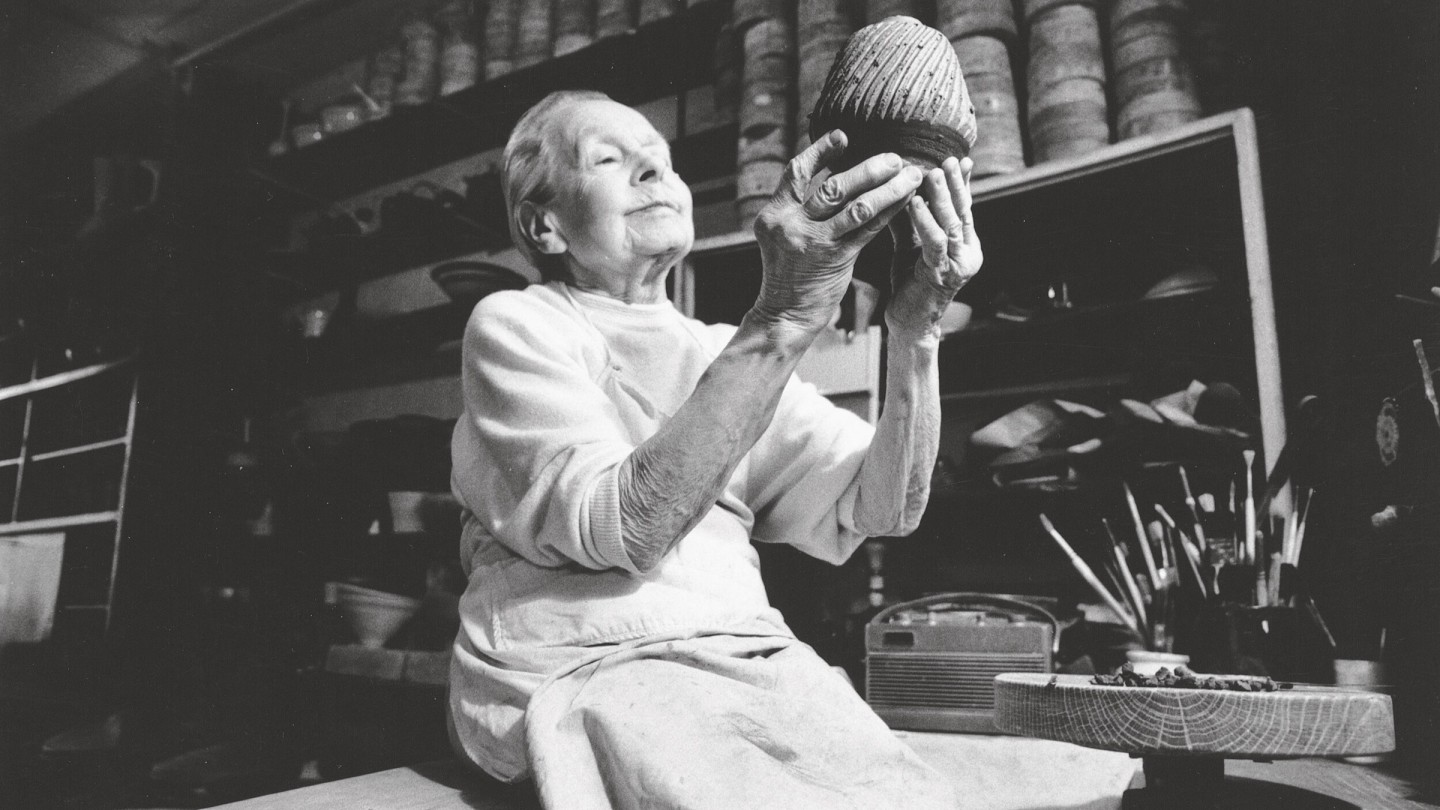

A diminutive figure who continues to loom large, her appetite for innovation remained undeterred. “If you wander around the ceramics collections at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, you’d struggle to find pots of the same confidence, flair or imaginative form as those of Rie,” says Nairne, who compares her blend of poise and panache to Gustav Klimt. “Even in her late seventies, she was still in the studio, splashing around the manganese.”

Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery is showing at Kettle’s Yard from 4 March to 25 June. A selection will also be shown at the Holburne Museum, Bath, from 14 July to 7 January 2024

Comments