‘I try to show the good’: photographer Dorothy Bohm finally gets her dues

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In memory of Dorothy Bohm, who has died aged 98, we are reposting this piece, originally published in June 2022

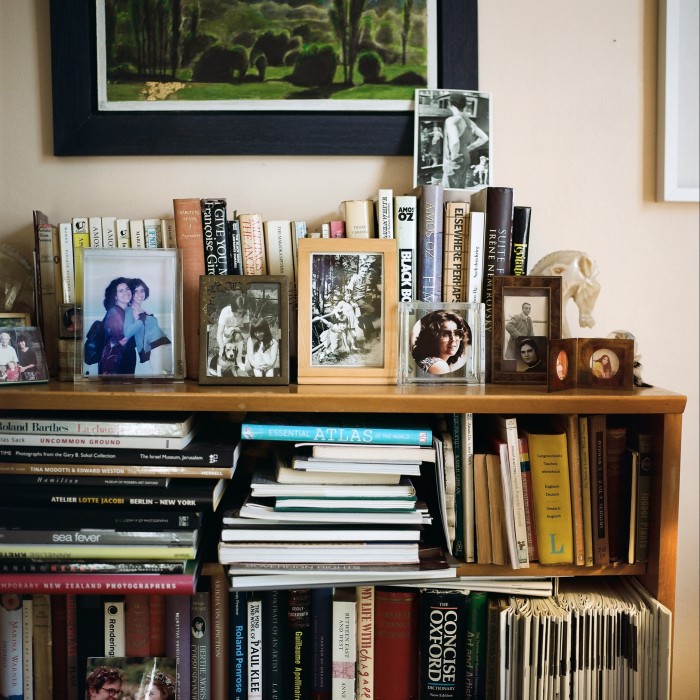

“I think there’s no other photographer who started out as I did,” says Dorothy Bohm. Seated at a circular table in the living room of her Hampstead home, which is next to the churchyard where Constable is buried, the 97-year-old is in a reflective mood. “I’ve had a very busy life,” she says. “I’m leaving behind a kind of photographic history – 32 countries, 20 books and 26 shows.”

Created over eight decades, Bohm’s body of work spans still life, portraiture, landscape, reportage and social documentary, capturing what she terms “poetic, mysterious, transitional moments”, first in monochrome and then in colour. Her achievements as one of Britain’s most prolific living photographers belie the fact that she is not better known outside the photographic community. But this looks set to change.

This month sees the opening of a survey of the American street photographer Vivian Maier at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes – the first of its kind in this country. This spring, the Brighton Museum staged a full retrospective of the 96-year-old US-born photographer Marilyn Stafford – her most comprehensive yet. A series of Bohm’s works is currently being assessed for inclusion in the National Portrait Gallery ahead of its reopening, and all in all, there’s a tangible sense that the work of female artists, long hiding in plain sight, is finally coming to the fore.

Others, frustrated at being relegated to the patriarchal medium’s sidelines, have formed collectives and staged shows (@womeninstreet), and pioneered research projects (@womeninphoto) dedicated to spotlighting the global richness of contemporary female talent. Such radical reframing of the female gaze is long overdue, says Anne Morin, curator of the Maier show: “It takes time for women image-makers to find their place in the history of photography, because it has been written by men. But the history of photography isn’t something that is fixed – it’s very much alive.”

Bohm’s place in that history is remarkable, regardless of her gender. Today, immaculately turned out in a fine gauge lilac knit, not a strand of her frost-white hair out of place and her eyes resolute as she recounts her story, it’s easy to see why Martin Parr dubbed her “the unstoppable Dorothy Bohm”. She was born Dorothea Israelit to a family of assimilated Lithuanian Jews; her father was a prominent industrialist in the former East Prussian town of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia). She was 14 when she was put on a train bound for England by him in June 1939. Germany had just invaded Memel, the harbour town that had become their home seven years previously. “I came to this country because of the Nazis,” she says vehemently. “I would not have survived.” Many of her classmates didn’t.

On that decisive day, as he stood on the station platform, her father, who was also an enthusiastic photographer, took off his Leica and hung it around her neck. “This might come in useful,” he told her. “It’s funny,” says Bohm. “He gave it to me but I had no early interest in photography at all. I didn’t even like being photographed – isn’t that strange?”

Bohm was separated from her family for the next 20 years. Many of her relatives were sent to labour camps in Siberia (the Nazis didn’t get them, she says – the Soviets did); she, meanwhile, found herself in a boarding school in the bucolic village of Ditchling in East Sussex. It was the start of a prolonged love affair both with Sussex, where she acquired a farm in the 1960s, and with England, which became her adopted home. She took up the camera at the suggestion of her father’s cousin Sam. As the family money had run out, forcing her to forgo her ambition of studying medicine, he thought it might provide a financially viable career.

“He’d noticed I was very observant as a child,” says Bohm. Sam organised a visit to the Baker Street studio of the prominent London portrait photographer Germaine Kanova that proved pivotal. “She was lovely and the work was wonderful. From that moment on I knew that photography was for me.”

In 1940, aged 16, Bohm left London to escape the Blitz and study photography at Manchester College of Technology, where she also met her late husband, Louis, a Polish Jew who had lost his mother and sister to war (“both of us started off with nothing at all”). Together they had two daughters, Monica and Yvonne. By 18, Bohm had a job in a local photographic studio as a printer, then a retoucher and finally an operator, and three years later – with the help of a £300 loan – she opened Studio Alexander on Manchester’s Market Street. Her income supported Louis as he completed his PhD. “I was the breadwinner at 21,” she says. “I’m still proud of that.”

The curator Dr Flavia Frigeri has been selecting Bohm’s pictures as part of a three-year project with the NPG, supported by Chanel. Its aim is to increase the collection’s representation of women as artists (the figure currently stands at a measly 12 per cent). For Frigeri, Bohm is a prominent figure among a swath of female émigrée photographers, including Laelia Goehr and Gerty Simon, who arrived in Britain in the 1930s and kickstarted a new era in photography: “They set up their own studios and essentially became businesswomen.” It was an auspicious moment, says Frigeri: “It allowed women to be financially independent, and to really come into their own at a time when painting and sculpture were still very much part of a male-dominated system.”

But it was beyond the confines of the portrait studio that Bohm really began to flourish. After the end of the second world war, she was able to travel – first to Ascona, the Swiss town on Lake Maggiore, then to Paris and New York, living in both cities for a time with her husband in the mid-1950s, and later to Mexico, South Africa and beyond. “Portraiture is important,” she says, “but when I started to photograph the world around me it opened up a big window.”

Early images convey a rough-around-the-edges Europe ravaged by war, where the glint of humanity still shines through the everyday. Children loiter mischievously in parks and on street corners; mothers sit on stoops cradling their babies; there are fairgrounds and circuses, and a sense of re-emerging social life. Bohm’s lens captures not just the daily hubbub but the emotion beneath it. “Dorothy Bohm knows her camera not only sees, it feels,” wrote Roland Penrose in the introduction to Bohm’s first book, A World Observed, in 1970. Her postwar work can be viewed as her effort to make sense of the environment into which she’d been so dramatically transplanted. “The photograph fulfils my deep need to stop things from disappearing,” she has said.

In the 1960s, Bohm was there to record a rapidly changing London. Her series of street-market pictures, which is filled with suited punters, lonesome stallholders, pearly kings and horse-drawn carts, continues to enthral. “We live in a first-person age when everyone has become a photographer, but the fact that Dorothy was already doing this 60 years ago makes these images feel incredibly relevant,” says Frigeri. “Her portrait of London captures the whole array of human feeling – the pleasures and the pains.” Bohm baulks at being described as a street photographer, but it’s surely a term that neatly encapsulates a great deal of her work? “I’m interested in people,” she insists. “For me that’s what I think it comes down to, but not only people on the street. I photograph for the love of seeing – and I still live through my eyes.”

Bohm believes that being a woman worked to her advantage when portraying people in places from London to Luxor, Tel-Aviv to Tokyo: “Because I’m a woman, I was never a threat. I have an innate sympathy and understanding of life.” When her first one-woman show took place at the ICA in 1969, the positivity of her People at Peace pictures was in stark relief to The Destruction Business series of images by Don McCullin that was shown in the adjacent gallery. “I’ve seen a lot,” she says. “But I don’t show the ugliness of life, I try to show the good.”

The popularity of the ICA show supercharged founder Sue Davies’s mission to set up The Photographer’s Gallery in 1971, where Bohm – who helped to establish it – worked as associate director for more than 15 years. This inspiring chapter saw Bohm nurture talents such as the young Martin Parr, and get to know everyone from Bill Brandt to Lee Miller, whose work she helped to bring back into the public eye. It was never a raison d’être to celebrate female photographers in particular at the gallery – but Bohm is keenly aware of the wider, seismic societal shifts that have taken place.

“In this long life of mine I’ve seen the tremendous progress that women have made,” she says. “It’s wonderful what they’ve achieved… I’m leaving behind a world that is very different.” But Bohm’s greatest wish, in a world where billions of images are carelessly created every single day, is more poetic than political: slow down and take the time to really see the world around you, she says. Look through your eyes, rather than your phone.

To buy original Dorothy Bohm black-and-white silver gelatin prints and C-type colour prints, email info@dorothybohm.com

Comments