Coronavirus: is investment management the weak link?

Simply sign up to the Financial services myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Even at the depths of the 2008 financial crisis, Cirque du Soleil’s acrobats kept twirling. While other companies tightened their belts or went under, the Canadian circus expanded its roster of flamboyant shows. But the coronavirus crisis proved a vault too far.

Last month, Cirque du Soleil was forced to cancel all shows and lay off 95 per cent of its employees. Two weeks ago, it missed a payment on its $900m of debts — sourced from the riskier leveraged loan market — and became the latest corporate victim of the virus. “The situation has been sudden and has put a very difficult strain on the company that we are actively working to manage,” Cirque du Soleil said.

The Canadian entertainment company is not alone. What started as a health crisis has morphed into an economic crisis of staggering proportions. Morgan Stanley predicts this year will see the deepest global recession since the Great Depression. Despite the recent market recovery, some investors and analysts still fear that a financial crisis could compound the economic damage.

“Today’s crisis is primarily a health crisis, but the size of it has led to an economic crisis, and that could in turn become a financial crisis,” says Tobias Adrian, head of the IMF’s markets department.

If that happens, it is likely to be a very different kind of financial crisis than a dozen years ago. The banking sector today largely looks healthy, after efforts to ensure that the bailouts of 2008 could never happen again. Measures varied from country to country, but all banks have been hit with stricter capital requirements, while the “proprietary” trading that banks conducted with their own money has mostly been killed off.

However, fragilities in the financial system remain — but elsewhere, and in a different form. Former officials, analysts and investors warn that risks appear to have migrated from the banks into a sprawling, multi-faceted investment industry which has grown tremendously over the past decade, partly by stepping into the void left by banks.

As vice-president of the European Central Bank at the peak of the eurozone crisis, Vítor Constâncio watched many of the region’s banks teeter on the edge. Now he believes that this shift shows how the overhaul that came out of 2008 was a job half done.

“Risks have grown enormously over the past decade,” he says. “We need to rethink the regulation of the non-bank part of the financial system, because they could amplify what could become a full-blown financial crisis.”

Financial crises are not mere economic downturns, or even synonymous with plummeting markets. The early 1980s saw a painful global recession caused by the US Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate rises, but outside of parts of the developing world that borrow heavily in dollars, it was not a financial crisis. Nor was the global stock market losing nearly half its value in the early 2000s, when the dotcom bubble burst.

Rather, financial crises are characterised by severe market instability, financial institutions keeling over, widespread debt defaults and even government bankruptcies. This causes the functioning of the financial system itself to break down, worsening whatever the core trigger was.

Action by central banks and government spending packages have helped buoy markets after the brutal volatility of March, when global equities slumped in the swiftest bear market in history. Rising hopes that the virus can be contained have even triggered a nervy rally. Nonetheless, the aftershocks are likely to be severe and manifold.

“This crisis shows both the pros and cons of everything we did after the last crisis,” says Ashish Shah, a senior executive at Goldman Sachs Asset Management. “2008 was a banking crisis, but this has been a capital markets crisis.”

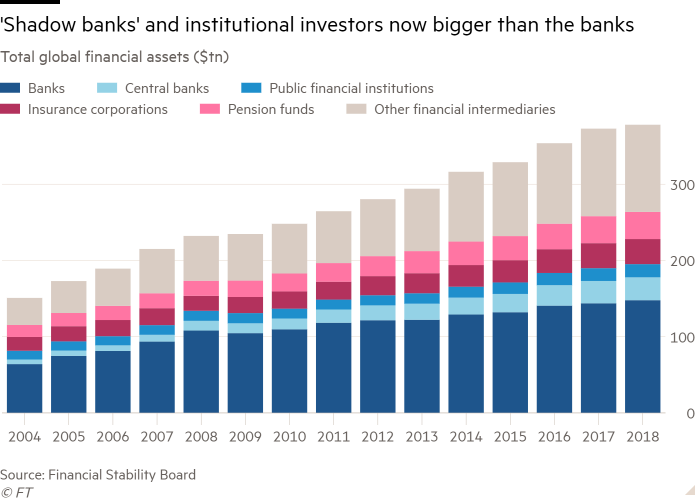

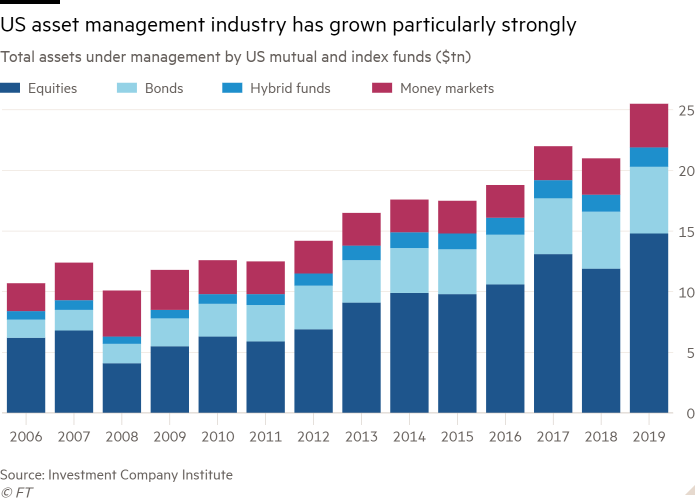

At the peak of the last crisis in 2008, the non-bank finance sector — ranging from traditional pension funds, insurers and mutual funds to racier industries like hedge funds and private equity — controlled assets worth about $98tn, according to the Financial Stability Board, making it slightly smaller than the global banking industry. Now its heft stands at well over $180tn, almost a fifth higher than overall banking assets, thanks to a bull market run over the past decade and a steady encroachment into parts of the financial system that was once the preserve of banks.

The vast majority of the industry consists of vital but fairly humdrum activities, investing in stock and bonds on behalf of everyone from sovereign wealth funds to private investors. But in some respects, this resembles what banks do — taking money that can be yanked out at a moment’s notice and putting it in longer-term investments.

This was a factor in the last financial crisis as well, leading some experts to dub them “shadow banks” and warn that they too were a danger to financial stability. The somewhat pejorative term has been binned, with regulators now preferring to talk about “markets-based finance”. But the rebranding has not altered the underlying fragility.

Editor’s note

The Financial Times is making key coronavirus coverage free to read to help everyone stay informed.

In the wake of 2008, regulators strengthened certain areas, such as money market funds — which invest in short-term, cash-like debt instruments — and derivatives, imposing greater transparency and pushing more trading on to regulated, formal exchanges. But by and large, the non-bank corners of the financial system were left untouched.

“We’ve done a lot to strengthen banks, and that’s a good thing. But we’ve done much less outside the banking system,” says Richard Berner, a finance professor at New York University and the former head of the US Treasury’s Office of Financial Research, which was set up to monitor systemic risks after 2008. “And that unlevel playing field tends to get regulatory arbitrage, with some activities simply migrating to less regulated entities.”

A classic case is how corporate lending is increasingly done by the bond market, rather than banks, especially for bigger companies. Bonds now account for well over half of all global debt, according to the Bank for International Settlements. But as interest rates have stayed low for a decade, investors have piled into many riskier corners of markets and racier strategies to eke out greater returns.

The rush to buy debt rated below investment grade — “junk” in industry parlance, but more politely known as high-yield — has been particularly strong. Cirque du Soleil’s debts, for example, are mostly lower-rated “leveraged loans”. UBS estimates that the US leveraged loan market alone has grown 76 per cent to over $1.3tn in the past decade. Most of these risky debts are bought by so-called collateralised loan obligations, a type of investment vehicle that has also swelled in popularity.

But lower-rated debt sometimes trades only infrequently even in tranquil markets. At times of distress, bouts of selling can send prices careering lower, or cause trading to freeze altogether.

The problem is that many funds offer investors the opportunity to withdraw their money whenever they feel like it. That raises the potential for bank run-like situations as jittery investors dash for the exit, forcing funds to dump their assets at fire sale valuations, sending prices spiralling even lower and triggering more outflows.

At the same time, stricter regulations have spurred many banks to reduce how much money they allocate towards acting as market intermediaries. Investors say deteriorating trading conditions were particularly noticeable in March, with even the US Treasury market suffering a bout of illiquidity.

But Bill Dudley, the former head of the New York Federal Reserve, argues that the “fundamental issue” is whether traditional mutual funds that invest in hard-to-trade assets should even allow daily investor withdrawals. “My view is no, and that’s something that should be looked at,” he says.

The boom in lower-rated debt and gummed-up trading conditions are far from the only manifestation of dangers migrating from banks to the investment industry. Many investors have also turned to an array of complex derivatives-based strategies to generate higher incomes, used leverage to enhance the returns of more stolid asset classes, or turned to more opaque “private” markets where assets hardly trade at all, such as infrastructure, real estate, direct lending and private equity.

The result became starkly apparent in the coronavirus-triggered market mayhem, according to Keith Skeoch, chief executive of Standard Life Aberdeen. “Risk has been taken out of banks, but punched out into other financial institutions,” he says. “There has been an incentive for investors to leverage up and search for yield. The unintended consequences weren’t immediately visible, but it’s becoming clear now.”

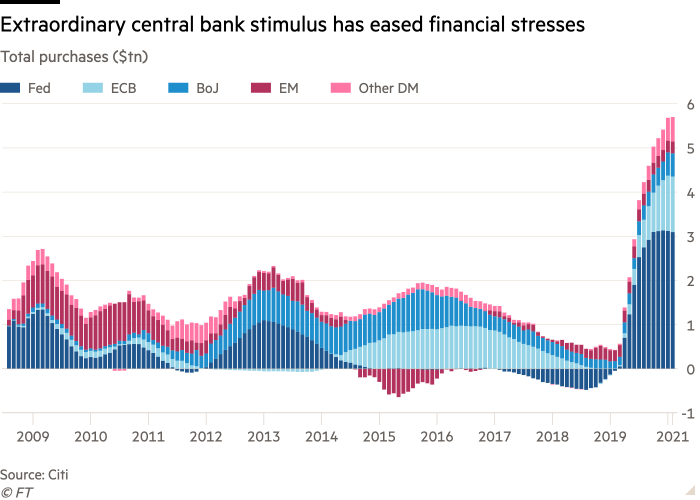

An extraordinarily aggressive response from central banks has soothed many — if not all — of the myriad financial stresses that emerged last month. It is likely that the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan and Bank of England will buy $5tn of bonds this year, two and half times as much as during the financial crisis peak, according to Citi.

Mr Dudley attributes the forcefulness both to the scale of the crisis and its core cause. “The villains last time were financial institutions, and there wasn’t a lot of sympathy for them. This time the enemy is coronavirus, so aggressive action isn’t as controversial,” he says.

As a sign of how markets are functioning relatively normally — considering the scale of the economic crisis — the New York Fed’s former head points to Carnival Corporation. The world’s largest cruise operator recently managed to raise $6.25bn through a sale of bonds and stock, despite its business collapsing. “Carnival had to pay up for it, but it got the funding it needed,” Mr Dudley says.

Moreover, the investment industry’s core business model is very different from banking. Asset managers are its locus but use little leverage, and losses befall investors in individual funds, not asset managers themselves. Even in an improbable scenario where one of the industry’s giants goes bust, it should not require a government bailout.

Therefore, while losses can be painful it is hard to envisage this morphing into a classic financial crisis, argues Peter Kraus, chief executive of Aperture Investors. “They will be spread over many more investors and a larger capital base, so the impact will be more manageable,” he says. “I don’t think that asset management poses a systemic risk in the way that the banks did in 2008.”

This is largely why the industry’s biggest players successfully fought tooth and nail to avoid being designated “systemically important” like major banks were in the wake of the crisis. Regulators have subsequently shifted their focus from individual entities to what they call an “activities-based approach”.

Nonetheless, the industry is not out of the woods. While asset managers themselves may be resilient, their individual funds — and therefore the overall market ecosystem — may yet prove fragile. Torrential outflows have slowed somewhat, but are likely to continue to test many investment vehicles. And in practice, money managers have already had their bailout moment, with the flurry of central bank backstops constituting an indirect rescue of many stressed strategies, some analysts argue.

While markets have bounced strongly since the lows of late March, many analysts are sceptical the rally will be sustained. The shock is likely to cause a spike in household, corporate and even sovereign bankruptcies that will maintain pressure on the financial system.

“The wave of downgrades and defaults will likely make people much more nervous than they are today,” says Matt King, a Citi strategist. “There’s still a massive gap between infection rates coming down, and economies actually going back to normal. And each day and each additional bankruptcy will make the situation worse. ”

Whatever happens with markets in the short run, the recent mayhem will focus regulatory attention on the non-bank corners of the financial system.

“This was a wake-up call. This was more virulent than I expected,” observes Mark Sobel, US chairman of the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, a think-tank. As a former senior Treasury official he was at the frontline of many previous crises, including the last one, and he says “non-banks are the hole in the regulatory system we never dealt with”.

Mr Skeoch agrees that there needs to be a wide-ranging debate, but argues that the post-2008 regulatory landscape should also be revisited and the negative unintended consequences dealt with. “My biggest worry is that we don’t learn the lessons of the past decade,” he says. “Regulations are always forged in the fiery furnace of recessions. But we have to think deeply about these issues.”

A wider-angle examination of the entire financial system is indeed vital, argues Mr Berner, who says one cannot “compartmentalise” the regulatory landscape for such a complex and codependent financial system.

“The crisis taught us to look at the system as a whole,” he says. “Banks and the economy depend on functioning markets, and markets depend on functioning banks and growth.”

Additional reporting by Siobhan Riding

Letter in response to this article:

Regulation is not a substitute for policy / From Dr Andy Sloan, Guernsey, CI

Comments