Freedom, style, sex, power: the fetishisation of the fast car

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

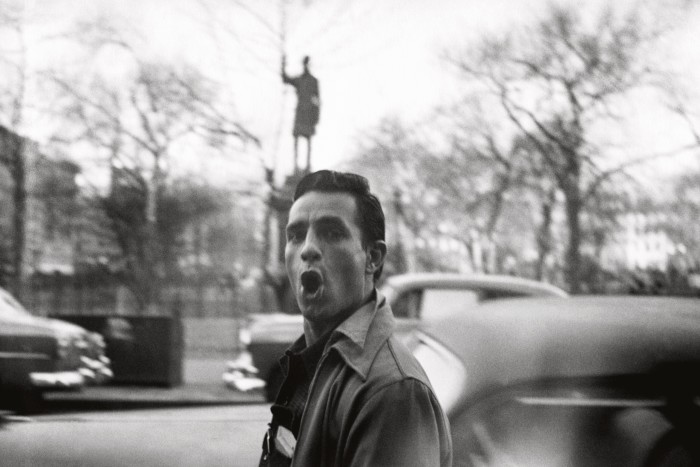

Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) has become a timeless classic, effortlessly transcending the druggy and solipsistic limitations of its Beat Generation milieu. It was a road trip, and his car was a ’49 Hudson, and Kerouac wrote not on sheets, but a continuous roll of paper, a device that surely aided his fluency. Here we read: Q. “Where we going, man?” A. “I don’t know but we gotta go.”

Truly, we are at the end of an era. You are reading this in the last days of the Age of Combustion, an art historical period as precise, as meaningful and as productive of beauty as the rococo or baroque. Of torment and distress too. Perhaps every era has its scary Inquisitions.

Jack Kerouac’s road trip is one of literature’s finest acknowledgements of the car in culture. That quote perfectly captures the automobile’s absurd promise and its shocking betrayal: drivers are tempted by a suggestion of freedom, but are ultimately incarcerated in one way or another.

But driving a car is not just about travel. Perhaps it never really was. It is also the experience of friction and the discipline of gears, an awareness of penetrating the atmosphere, the thrill of speed, an opportunity to test your perceptions, nerves and reflexes. Of finding a vista of escape. Occasionally of confronting fear. And all of this excitement on a daily basis. A daily commute offers raw sensual experience that, a century ago, was the stuff of deranged fantasy to the Futurists.

Tom Wolfe said that cars are “freedom, style, sex, power, motion, colour… everything”. And indeed, from Huckleberry Finn to Grand Theft Auto, via Kerouac and Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, America reads like a road epic. Consider F Scott Fitzgerald, the great poet of ruined glamour and wasted promise. In 1920, flush with the advance from This Side of Paradise, he fired up his 1918 Marmon, bundled his wife into the passenger seat and drove from Connecticut to Alabama, so Zelda could rediscover the peaches and biscuits of her southern youth. They were looking for a lost Golden Age, a quest which later became the subject of The Great Gatsby. (In the book, a yellow Rolls-Royce plays an important part.) Fitzgerald turned this eight-day journey into a series of articles, which appeared in the US Motor magazine, in 1924, eventually published in book form, in 2011, as The Cruise of the Rolling Junk.

The reality was one of bust axles, blow-outs and misdirections, since Zelda could not read a map. Scott and Zelda never found their Golden Age, but Fitzgerald could not let the fantasy go. He described “an ethereal picture of how we would roll southward along the glittering boulevards of many cities, then, by way of quiet lanes and fragrant hollows whose honeysuckle branches would ruffle our hair with white sweet fingers”. That’s what a Marmon could do for you. On return, Zelda icily wrote “the joys of motoring are more-or-less fictional”.

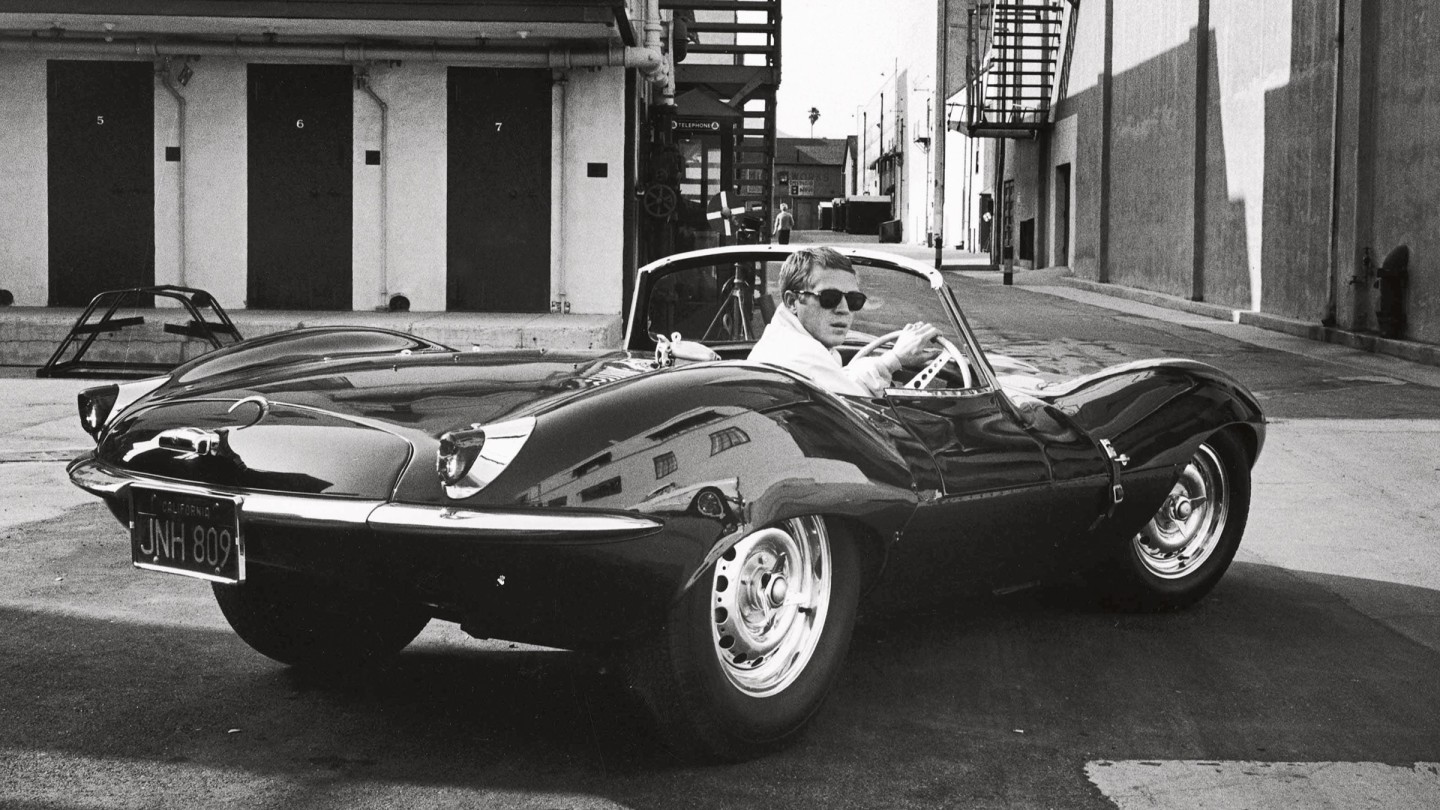

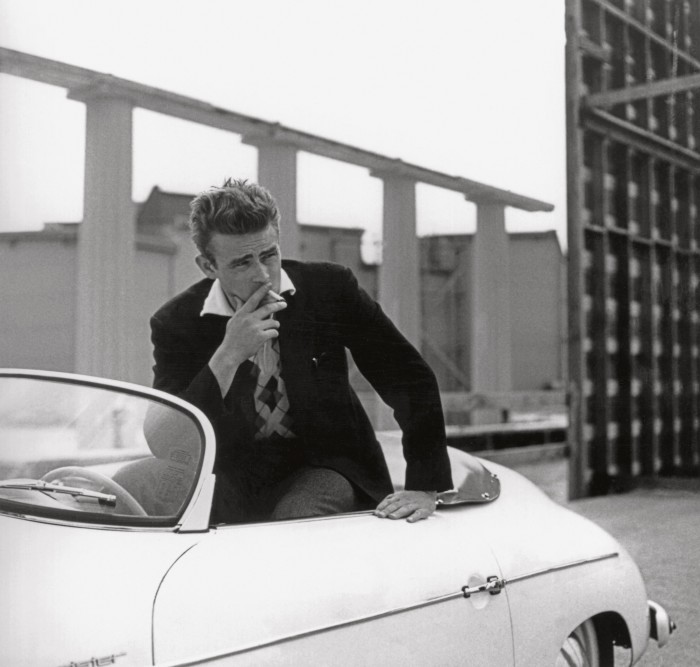

Even as the private car ceases to be the paramount consumer product, its extraordinary imagery will survive. Car design, along with pop music and the movies, was one of the defining activities of the 20th century. Significantly, each was a collective activity with more than one auteur. Consider the car’s role in the cinema. The title Rebel Without a Cause, the 1955 film that made James Dean famous, was taken from a psychological study about disturbed youth. In the film, his car was a 1949 Mercury Club Coupe with a 255 cu in (4.2 litre) flathead V8 – a car that later became a favourite of Californian hot-rodders and customisers, the inspiration of Tom Wolfe’s remark. A month before Rebel was released, a 24-year-old Dean was killed in the Californian desert when his Porsche 550 Spyder collided with a Ford Tudor. This lent Dean’s lead sled a sinister posthumous cultishness as a memorial to destroyed youth, while enhancing Porsche’s reputation for danger.

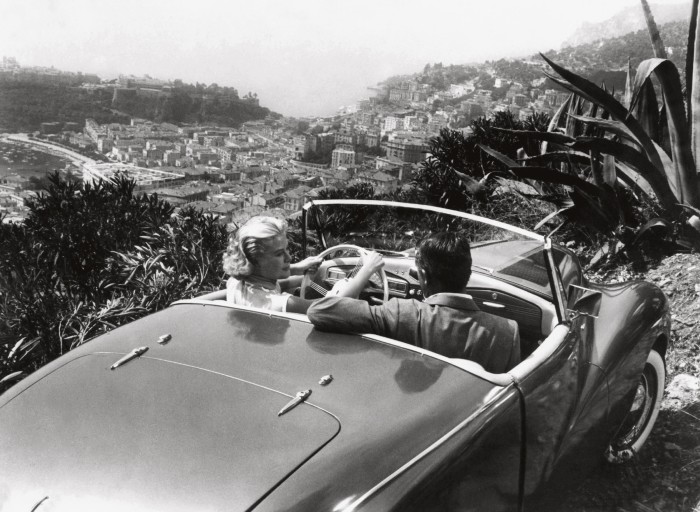

Alfred Hitchcock understood how cars convey meaning. His wife Alma chose the pretty, metallic ice-blue Sunbeam Alpine Series III that Grace Kelly drove in To Catch a Thief, the masterpiece romantic comedy-thriller. In export markets, the Alpine was intended to fit between the primitive MG TD and the more sophisticated Jaguar XK120. It was also the perfect fit for the beautiful but chilly Grace Kelly character. Her stylish drive along the Grande Corniche with a soundtrack of wince-making squeals of cross-ply Dunlop tyres and scrunching gravel, with an immaculately dressed Cary Grant as a composed, but very nervous, cat-burglar passenger, is one of cinema’s great car sequences. So influential was the film in creating a popular concept of continental glamour, the views of Monte Carlo from the Corniche later became a cliché in car advertising.

Like To Catch a Thief, Mike Nichols’ The Graduate, of 1967, was a superlative film based on a mediocre novel. It is one of the greatest rite-of-passage-coming-of-age movies, combining motifs of forbidden sex, rebellion, redemption, and an Alfa Romeo plays a leading role as a means of escape, all set to unforgettable sing-along music by Simon and Garfunkel. The Alfa is a 1966 Series I Duetto with the classic 1.6-litre twin-cam four. Its body was drawn by Franco Martinengo of Pininfarina, and this early version has the distinctive curvaceous osso di seppia (cuttlefish) tail. The car’s well-known frailties become a dramatic moment in the film when the Duetto runs out of petrol in the Californian desert because of a faulty fuel gauge. But the great visual moment in the film is the Dustin Hoffman character, Benjamin Braddock, rushing over San Francisco’s Bay Bridge on the way to frustrate the young Ms Robinson’s wedding. The Rosso Corsa Alfa is seen from above, travelling from the Embarcadero to Yerba Buena Island (and also going the wrong way through the Gaviota Tunnel on US Route 101). The speeding car somehow conveys a perfect expression of wistful longing, and the elegant Alfa confers on Hoffman-Braddock the keenest sense of eroticised style and nervous urgency. But what does the greatest movie franchise of them all tell us about cars?

If William Lyons had not been so epically tight-fisted, James Bond’s car would have been an E-type. The producers tried to blag freebie Jaguars, but Lyons was disinclined to deal. So, 007 got a DB5. (But that was only in Goldfinger, the third Bond film – Bond’s first movie car was a Sunbeam Alpine, successor to Grace Kelly’s.) It’s an assumption of pop-culture analysis that cars in the cinema add meaning and mystique to heroes and villains. Of course, Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming, had already brought impressive amounts of brand-related snobbery to his masterpieces. His own taste for cars was altogether different: he drove Thunderbirds because he enjoyed their power and gadgets. Latterly, a Studebaker Avanti with an incongruous Home-Counties-style badge-bar. Meanwhile, the real-life spy Kim Philby drove a grim Humber from the Ministry of Defence carpool. So, these are the precious brand values Connery brought to Aston Martin: sadism, sexism, snobbery, hedonism, refined violence, good taste, a sharp but relaxed sense of style, gentle wit and muscle. Really, you could not have a more valuable set of associations for fast cars.

Auto-fiction

In 1909, EM Forster wrote his short story The Machine Stops. It’s a gloomy tale. People live underground, paying tribute to a remote and scary technical entity known as The Machine. They no longer travel because they use video conferencing and text. Sound familiar? And then: The Machine stops. When the hot server farms in the Arizona desert melt because there is no more gasoline to power the generators that power the air-con they devour, our machine will stop too. The economist John Maynard Keynes said by about now we would all be so rich, no one would have to work. He was wrong too. The Poet Laureate of Dystopia, JG Ballard, predicted that by about now private cars would not be allowed on public roads. Instead, “enthusiasts” would use them under supervision in enclosed “motoring parks”.

They say the autonomous electric car will set us free. But the driverless car will, in every sense, lack soul. And people like soul, even if it is their prison warder. And autonomy ignores the psychological reality of car ownership which is, to be honest, based on concepts of pride and prowess and personality. We’re told that the steering wheel will disappear. But what will take its place? “The screen will replace the steering wheel. You’ll watch the news as you travel. Or movies.” So says Norman Foster, an architect so committed to a tech future that he has designed a glass “infinite loop” for Apple at its Cupertino HQ.

It seems the semantics of the car will no longer be focused on selfish notions of enthronement, ownership and dominance, but a utopian one of shared space. Cars may become ever more like mobile architecture: spaces to be enjoyed. But what will replace the fascination and romance? Well-designed screens will have their allure, but the thirst for style, power and control may not be easily quenched.

Norman Foster concludes: “And when you arrive, after a pacific journey staring at a screen, you’ll get into your classic car and indulge yourself on the track.” JG Ballard’s prediction was, perhaps, not so very wrong.

Extracted from The Age of Combustion – Notes on Automobile Design by Stephen Bayley, published by Circa at £19.95

Comments