A third of start-ups aim for social good

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Social entrepreneurship, once a niche area, is spreading its wings. Across the world, almost half as many people are creating ventures with a primarily social or environmental purpose as those with a solely commercial aim, according to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), a multi-country study.

The movement is driven mainly by younger entrepreneurs and its growth has taken place against a backdrop of corporate scandals in mainstream businesses, such as Enron in 2001, or the more recent VW emissions scandal, that have brought capitalism’s values into question. The question is whether social entrepreneurship can generate sufficient economic impact to ensure its survival. More needs to be done to improve access to finance, to grow businesses to significant scale and to measure their social effect, experts say.

“Social entrepreneurship has gone mainstream and global,” argues Peter Drobac, a doctor who created healthcare ventures in Rwanda, including a university and incubators to develop innovation in delivering treatments.

Dr Drobac, now director of the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship at Oxford’s Saïd Business School, was inspired to get into the field 20 years ago when HIV infection was running unchecked. “Younger generations in my experience are much more deeply connected to the world and to societal challenges. They want careers that allow them to create positive change,” he says.

Other factors, Dr Drobac adds, include the changing nature of work, “which means that the prospect of spending one’s entire career in the same company is becoming vanishingly small”. At the same time, technology is creating opportunities for disruptive innovation in sectors such as education and healthcare.

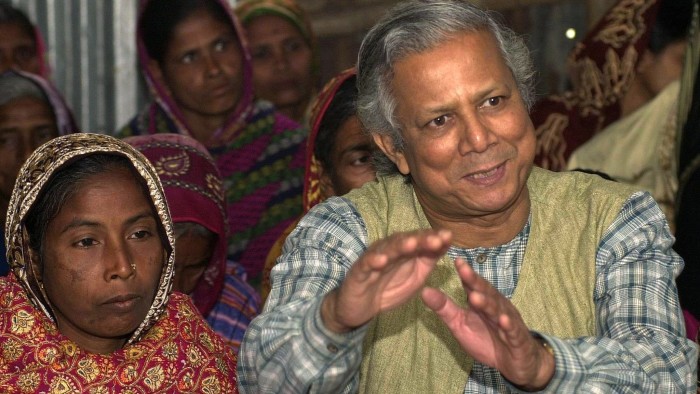

While research suggests the majority of social entrepreneurs worldwide are young, the movement has been inspired by figures such as Muhammad Yunus. The septuagenarian Bangladeshi founder of Grameen Bank won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for pioneering microcredit — loans for entrepreneurs too poor to get traditional bank loans, many of them women.

High-profile social entrepreneurs also include Blake Mycoskie, founder of Toms Shoes, which donates one pair to a poor child for every pair sold; John Bird, founder of The Big Issue, the UK magazine sold by homeless people; Bill Drayton, founder of Ashoka, an organisation that supports and develops social entrepreneurs worldwide; and Katie Martinez, founder of Elegantees, a fashion company that employs survivors of sex trafficking.

Social enterprises can be structured as for-profit, non-profit or hybrid. The GEM study calculated in 2016 that 3.2 per cent of the world’s population was engaged in starting a social venture (compared with 7.6 per cent starting commercial ventures) and 3.7 per cent running an established one.

Victor Adebowale, chief executive of Turning Point, a social care enterprise, and chairman of Social Enterprise UK, representing the sector, believes prospects are bright.

“Worldwide you are seeing pretty much exponential growth. Imagine what could happen if we had a more inclusive economy in which social enterprise was seen as a central pillar. I think we would be transforming the way the economy works,” he says.

Britain has 99,000 social enterprises employing 1.44m people, or almost 5 per cent of total employment, according to government data. Many are in areas such as health and education, though companies in any sector can be run as a social enterprise.

Lord Adebowale warns that despite the sector’s progress, “it’s really difficult to find capital for social enterprises”, a problem also seen in other countries.

One way of increasing funding would be through more use of social investment vehicles. These have been around for years and have generated interest in impact investing, which aims to deliver returns by placing a value on a measured social improvement. A UK government review last year found that younger savers are increasingly interested in social investment products but the industry is not keeping up with demand.

“Reasons for a lack of investable products include the fact that social impact investment opportunities can be difficult to identify and crystallise; many are early stage, implying material credit and liquidity risk,” the review said.

Stuart Parkinson, global head of product, investments and collaboration at HSBC Private Banking, is optimistic that the capital gap can be plugged. “We are seeing angel investors begin to target companies where they see not only commercial viability, but also contribution to a sustainability agenda,” he says.

Comments