Japan, land of the rising investment prospects

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

An easy quiz question to start. Put these equity markets in order of how they have performed over the past decade: US, UK, Europe, emerging markets and Japan. No prizes for calling the US top. The S&P 500 index is up nearly 14 per cent a year compound in sterling.

It might surprise you to find that Japan comes second, with the Nikkei growing at 9.8 per cent compound. That is well ahead of the UK FTSE All-Share, at 2.6 per cent, and the Europe Stoxx index at 3.3 per cent. You may also be surprised to learn that the MSCI Emerging Markets index managed only 2.9 per cent.

Many investors believe that the Japanese stock market had a huge boom in the 1980s, that it suffered a mammoth bust at the end of that period and that it has malingered ever since under the weight of deflation and a shrinking population.

Certainly, deflation and demographics have been a drag on the economy. Yet those returns of close to 10 per cent a year illustrate the maxim that a stock market does not always reflect what is happening economically.

One reason is that a country’s stock market can be dominated by multinational companies, much of whose earnings come from overseas. That is true of the Nikkei.

Even if an economy is growing slowly, if you buy the stocks cheaply they can perform. Ten years ago the Japanese equity market was deeply out of favour. Many companies traded on very low multiples, sometimes below the book value on their balance sheet.

Selecting companies with low price-to-book ratios is the key strategy recommended by the legendary investor Benjamin Graham in his first book, Security Analysis, which he co-authored in 1934 after the Wall Street Crash had cost him most of his savings.

Graham’s approach worked particularly well for investors in Japan after Shinzo Abe became prime minister in December 2012. Abe was intent on structural reforms to make Japanese companies more attractive to investors. In 2008, a vice-minister of economy, trade and industry had described shareholders as “stupid, greedy, adulterous, irresponsible and threatening”.

Abe had a different view. Japanese companies were often protected from shareholders’ intervention or takeover, encouraging moribund management. Some companies held large cash surpluses or valuable shareholdings in related companies. This may have allowed them to cope relatively well with the global financial crisis of 2008, but overseas investors often regarded such strong balance sheets as “lazy money” or a sign of a clubby mentality.

Abe encouraged companies to raise their profitability, even if it meant losing some of their dominant market share. He improved governance, accelerated the removal of poor managers and sought to find a better balance between the interests of shareholders and employees.

Return on equity for Japanese stocks increased from around 5 per cent in 2012 to nearer 10 per cent in the summer of 2018.

Nippon Telephone is a good example of a Japanese company that delivered improved returns for shareholders. Over the past decade its shares have returned more than 10 per cent a year. Despite seeing very little growth in revenue over the period, the company has trebled underlying earnings to over ¥300 from ¥107 by focusing on efficiency and by buying back shares regularly with excess cash.

Many say reforms have not gone far enough, but Abenomics has helped. What next?

The Japanese stock market continues to house a long list of companies that most of us know well. The largest, Toyota, is just launching its battery electric vehicle range and has plans for hydrogen-powered trucks. Sony is now better known for its games consoles than for making music centres. These companies are evolving and responding to the opportunities and threats they face.

Large Japanese companies may have shares listed in overseas markets, which means they can be easily bought here. But the most interesting Japanese companies are often not available on the main platforms used by retail investors. There are specialist Japan funds in the UK with expert managers looking for these opportunities who have the patient approach often needed.

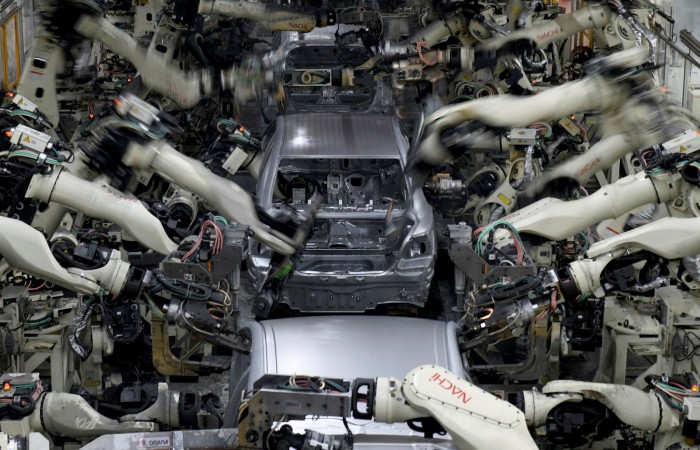

As a global manager, I have always found it invaluable to go out there twice a year. We are particularly keen on the Japanese automation sector. Industrial robots used to handle heavy lumps of metal to make cars. The technology and mechanics are now so advanced that robots can do delicate surgical procedures — and with better outcomes than the most experienced humans.

Automation is spreading from industrial, automotive and semiconductor sectors into clothing, food handling and retail distribution areas. Japanese companies manufacture components, the robots themselves and the software that co-ordinates them and makes them safe to work alongside humans.

Many of the managers are themselves skilled engineers, in the same way that many of the Silicon Valley unicorns are run by internet geeks. Confined to London, I had a call with the president of the leading automation company, Yaskawa, last month. He knew his products: it was clear that if you gave him a pot of spanners and a screwdriver, he could build a robot for you.

Equity markets are currently anticipating a sharp improvement in economies as lockdown ends. The rise in industrial investment and consumer spending should benefit a number of Japanese-quoted companies, even if their own economy remains subdued as measures to vaccinate the population appear late.

There are other reasons to invest. Japan gives you developed market access to China and the Asia growth story — it is a China proxy with better governance. Japan often performs better than other economies in downturns. And if the current boom turns inflationary, as some fear, this is one economy that might actually benefit from higher inflation. It seems ironic that for years investors used the Japanese government’s high debt levels as an excuse for avoiding its stock markets. Now most Western countries are following the Japanese model.

Nevertheless, there are risk factors to investing in Japan, and debt remains one of them. Some fear that the economy will at some point collapse under the weight of its government borrowing, which amounts to over 2.4 times GDP. For decades, this has caused bond investors to sell short Japanese government bonds (JGBs) – and lose money doing so. Indeed, even this year when US government bonds have fallen and made profits for bond short-sellers, JGBs have been stable yet again.

One explanation for this is that a large share of JGBs are held domestically and that the very low yields may not be a problem as an investment for pensioners when the cost of living keeps falling. However, rising inflationary pressures, like those we see currently in the prices of steel, copper and agricultural products, will affect Japan as much as other countries and this could make the bond pile less stable.

Another short-term concern is Covid levels in Japan and Asia. These have been rising and vaccination rates have been very slow. To put this in context, there have been 760,000 positive Covid tests in Japan so far, compared with 4.5m in the UK – that’s 6 per 1,000 population compared with 66 per 1,000. Perhaps this explains why the authorities are prepared to go ahead with the Tokyo Olympics, albeit with tight precautions.

Japanese equities were once a core part of every global portfolio. They seem to have been replaced somewhat by emerging market holdings. In my view you still get a lot more company for your money in Japan – more established technology, excellent product development and modest valuations. This is why we hold just under 10 per cent in Japan, compared with the MSCI All World index weighting of 7.6 per cent.

When I first travelled to Japan in 2001, I was surprised that this economy that I had heard so many bad things about was in such good shape. It had excellent airports, great railways and superb food. I thought the large number of people wearing masks while travelling on the subway were paranoid, disease-averse commuters. In fact, many had a cold and wore a mask to avoid others catching it.

Now we are all wearing masks, perhaps it is time to cast aside old prejudices. This is a country it can profit you to get to know more deeply.

Simon Edelsten is co-manager of the Mid Wynd International Investment Trust and the Artemis Global Select Fund.

Comments