In 2050, will gig economy workers answer to robo-bosses?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 2050, it is possible that up to 5bn of the 6bn workers worldwide will be employed in the gig economy and their boss could be a piece of software.

As freelancers, they are likely to be working from home on 20 projects with as many teams or companies. This will increase the importance of collaborative working and professional networks, flattening traditional hierarchies in organisations as most people no longer have a formal boss to help advance their careers.

At the same time, as technology develops, interaction between humans and machines will increase. More basic management tasks, such as checking project progress, will be completed by software, reducing the need for mid-level leaders.

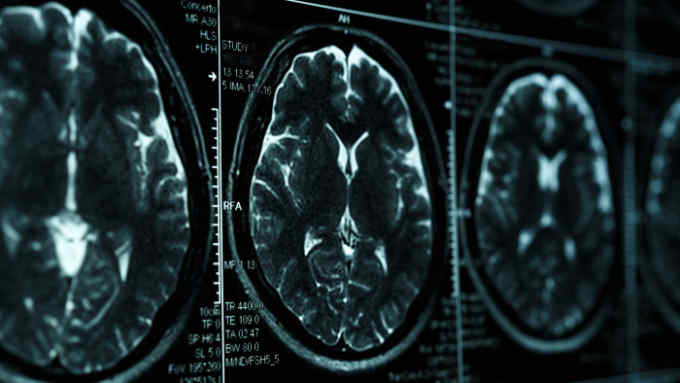

Of the 6bn working population, just 1bn will be in a job we recognise today — but they will complete it with supercharged brainpower, according to Jerome Glenn, executive director of the Millennium Project, a global think-tank of futurists, scientists, business partners and policymakers. He says an elite group of professionals will use a “genius app” to augment their intelligence so they can carry out knowledge-specific roles such as theoretical physics.

Until this enhanced intelligence spreads more widely, as Mr Glenn forecasts, everyone else will be left completing a range of activities with a machine manager. “Your boss could well be an interaction with software,” says Mr Glenn, who is lead author of Work/Technology 2050, a Millennium Project report published in September that presents scenarios on the impact of robotics and the future of work.

“Robo-bosses” will take over tedious management tasks, agrees Shivvy Jervis, a UK-based futurologist. Amy Fletcher, associate professor of political science and international relations at Canterbury university in Christchurch, New Zealand, cites the paralegal profession today as an example of the type of changes faced by managers. It is under threat from so-called lawbots that can “churn through cases faster than humans” — but only on low-level tasks.

Thanks to this, middle-management jobs will not disappear, Ms Fletcher says. “Tasks will be automated, with a lot more interaction between humans and machines, but people-oriented work will become valuable,” she says. Employees will still need human managers to discuss problems and career development.

Yet the move towards freelance working will change traditional hierarchies as workers will look to their professional networks rather than up the management chain to advance their careers. The emphasis will be on how “you influence the industry you are in”, Ms Jervis says.

Organisations will need to consider how talent, culture and skills are embedded in a world where companies are managed more as professional communities and less like static hierarchies. It is possible there will be fewer face-to-face meetings at work but human interaction, when it happens, will still be important as people will need to maximise their contacts to make progress.

“People will need to think about who their connections are and how they can scale and leverage the expertise around them,” says Rob Cross, the Edward A Madden professor of global business at Babson College, Massachusetts.

Even with this emphasis, he does not believe all managerial titles will be abolished. “It will be phenomenally overwhelming for people if layers are taken out to streamline decisions. Collaboration can then become unsustainable.”

The employees most likely to succeed will be those who are flexible, adaptable and creative, and who can work in a diverse organisation with a flatter structure, says Ms Fletcher.

This devolution of management will present social challenges, too. Ms Fletcher points to Amazon where a few people have done well out of the online retailer but there is “not a lot of middle management”.

A flatter organisation with less job hierarchy could create a world where the “middle class falls backwards” with fewer well-paid jobs. It may also leave a vacuum for employees in terms of support.

With the Uber model, for example, people can set their own schedules. Without regulation, however, the model “leads to a race to the bottom, with people working almost constantly”, says Ms Fletcher, especially since jobs are under stress from automation and there are fewer middle managers to monitor workloads.

“What happens in 2050 depends very much on the choices we start to make now. If we let it run its course, it could end up in a bad place. We need to ask ourselves what is the point of a job? What are corporations? These are the questions we will need to answer to get to a happy future rather than a dystopian version,” she says.

Among all this disruption, workers who succeed will need to look after their wellbeing, balancing the demands from clients, bosses and domestic life, says Prof Cross. But then perhaps they can leave all that to an AI assistant.

Comments