The bull case for investing in China

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is chief global investment strategist at Charles Schwab

For many investors, recent regulatory actions by China have been unnerving. It has sparked fears that the country has made a sudden and risky policy shift that is anti-business and anti-investor.

The slow slide in China’s stock market from its February peak sharply accelerated in the third quarter. Investors seemed to switch from calmly interpreting regulators’ actions as only focused on a few big tech firms to alarm that no industry is isolated from a sudden rush of regulatory reforms.

Fears spread that changes aimed at reining in the excess leverage of property developers, such as Evergrande, could bring the risk of a financial and consumer meltdown.

The truth is that the rapid and targeted regulatory changes shaking China’s stock market are not uncommon and often are followed by sharp rebounds in share prices driven by broadly favourable policy actions.

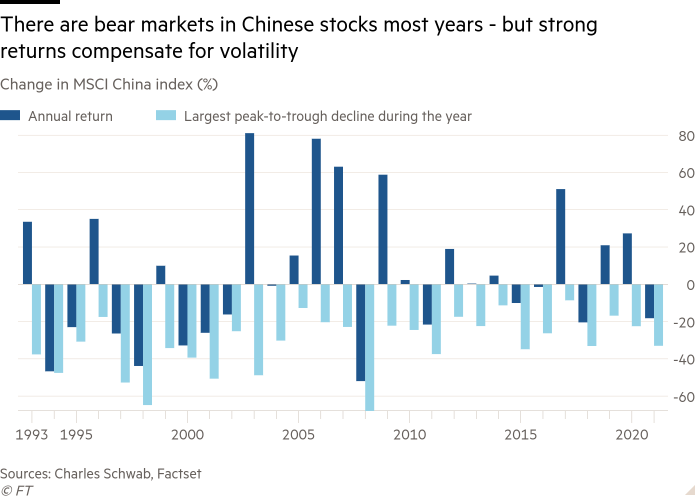

In fact, this year’s peak-to-trough retreat of 33 per cent in China’s stock market is close to the 28 per cent average annual drawdown over the past 20 years, measured by the MSCI China Index.

It can be easy to forget that there is a bear market nearly every year in Chinese stocks (17 of the past 20 years), usually driven by some policy issue.

Historically, investors have tended to be compensated for this heightened volatility with strong annualised total returns. From August 2001 to August 2021, the MSCI China Index produced an annualised total return of 12.3 per cent, outperforming the 9.3 per cent produced by the S&P 500.

Investors’ concerns have been focused on sectors that are being negatively affected by China’s new regulations — internet, education and gaming, for example. Many of the issues China is targeting are also in the crosshairs of policymakers in Washington or Brussels but changes are slower. In China’s one party state, things can seem to happen overnight and be temporarily jarring to markets.

But the regulatory tightening worrying the markets is only one side of the coin. There are also sectors that are being supported by the government — such as semiconductors, green technologies and consumer brands. In other words, the government is attempting to restructure the economy and not solely crack down on private business.

There is plenty of entrepreneurship in China driving growth outside the areas being targeted for reform by the government. In fact, China’s economy is now almost entirely driven by private businesses.

Almost 87 per cent of employment in China is in private companies and private firms also account for 88 per cent of China’s exports, according to data gathered by consultants McKinsey.

In China’s case, it has some unique characteristics that reduce the threat of a crisis: the Chinese government controls both sides of the banking system (lenders and borrowers).

The largest borrowers are state-owned enterprises, and China’s reliance on internal sources of funding makes it more resilient. China’s vast domestic capital means it is not very vulnerable to a sudden withdrawal of capital by foreigners that would shock the economy into a recession.

On the lender side, the government holds sizeable stakes in the large, systemically important banks and could recapitalise them in the event of a crisis. Additionally, Chinese banks do not appear to have used leverage and derivatives to the extent western banks did in the years leading up to the financial crisis in 2008.

Longer-term investors in emerging market stocks might draw some degree of comfort knowing that the bear market in China is tied to near-term policy uncertainty, rather than a broader economic downturn that could linger.

Other emerging markets have not followed along in the bear plunge, with emerging market stocks excluding China still up more than 10 per cent this year to September 27.

Timing moves in any market is difficult and China can be even more challenging. There is risk that the regulatory rollout may continue, property prices could fall and undermine consumer confidence, not to mention the potential for Covid-19 related concerns and the tense US-China relationship to weigh on the growth outlook.

Yet, the potential for the regulatory intensity to ease without leaving significant economic damage suggests the balance of risks could be tilted to the upside from current levels.

High volatility is one reason why having a long-term perspective is especially important for emerging market investors. Long-term investors in emerging markets such as China know that patience may be rewarded with strong gains.

Comments