Putin has ‘lost the energy war’, top trader claims as he ends bets on high gas price

Simply sign up to the Energy crisis myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Russian president Vladimir Putin has “lost the energy war” and the worst of the European gas and power crisis has passed, according to Pierre Andurand, one of the world’s top-performing traders in the sector.

Andurand, whose energy focused hedge funds have enjoyed three bumper years of returns during the coronavirus pandemic, said he had closed out all his positions in natural gas markets because last year’s price surge to record levels was unlikely to be repeated, with Europe learning rapidly to live without Russian gas.

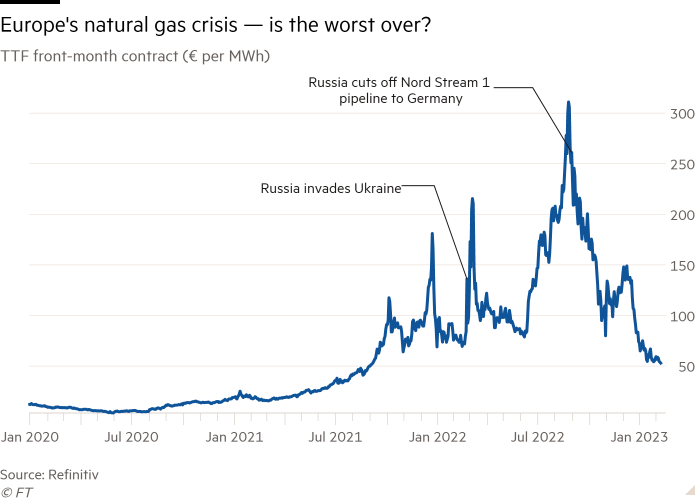

Deep cuts to Russian gas exports in retaliation for western support for Ukraine drove the European benchmark price above €300 a megawatt hour in August, more than 10 times its normal level. But in recent months it has tumbled back to about €50/MWh — still historically high but far more manageable for European economies mired in a cost of living crisis.

“I think Putin lost the energy war,” Andurand said in an interview with the Financial Times. “Very high natural gas and power prices in Europe were extremely bad for the world economy but now they have come back to a more reasonable level. If gas prices stay here there will be much less worry about inflation and interest rates rises. There’s no more fear of an energy crisis.

“Now that Europe is getting used to living without Russian gas why would they ever go back?” he added.

If correct, the French kick-boxing enthusiast’s call spells the end of one of the most lucrative hedge fund trades of recent years. Some managers made significant profits from rocketing European gas prices after Russia began squeezing supplies to Europe in 2021 before slashing exports after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine last February.

Andurand, whose firm Andurand Capital manages $1.4bn in assets, saw his Commodities Discretionary Enhanced fund gain some 650 per cent from the start of 2020 until the end of last year. The former Goldman Sachs and Vitol energy trader made his name by calling many of the big moves in oil and other energy commodities over the past two decades, including oil prices turning negative during the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic.

Andurand, whose fund is down 3 per cent so far in 2023, said Putin had erred in cutting gas exports to Europe last year, as although he succeeded in driving prices higher temporarily he had underestimated buyers’ ability to adapt.

“I think it was a massive miscalculation over who had the leverage by Putin, in the same way he miscalculated how Ukraine would fight back and the west would be united,” Andurand said.

“Russia has lost its biggest customer forever, and it will take at least a decade to bring enough pipelines [to redirect those gas sales] to Asia. Once Russia can only sell gas to China, Beijing will be in a position to decide the price.”

While Andurand argued the gas and power crisis was coming to an end, he still said there was the potential for big moves in the commodity for which he is best known. Oil prices, he said, had fallen too far in recent months and were set to rally as China’s economic rebound from the end of its zero-Covid policies accelerates.

Oil could hit $140 a barrel later in 2023, Andurand said, arguing that the market is taking too short-term a view, both because of losses suffered last year and also due to the growing dominance of multi-manager and quant hedge funds in it.

“The reopening of China is going to lead to a lot more oil demand growth than expected,” Andurand said, adding he had scaled back oil positions in the second half of last year as prices fell, but had upped his bets in mid-December.

“It might take a couple of months for the market to recognise the scale of the demand increase we’re seeing,” he added, arguing that Chinese-led global consumption could rise by as much as 4mn barrels a day this year compared with just over 1mn b/d average annual growth normally.

“That would mean really large inventory draws and the market will get very tight,” Andurand said, adding that $140 was “not a crazy high price” once adjusted for inflation as oil’s all-time peak of $147 a barrel was 15 years ago.

Oil briefly surged to $139 a barrel last year shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but has fallen back to $83 a barrel after it became clear the effect of western sanctions on the volume of Moscow’s oil exports had been limited.

Andurand said he was not counting on the recent tightening of western sanctions on Russia to boost the price as he predicted the measures were unlikely to remove too many barrels from the market, with Moscow choosing to sell its oil at a discount to attract new customers in Asia.

“I don’t want to bet on a large supply disruption from Russia as they have shown a willingness to move the barrels even if at very low prices,” Andurand said.

“My base case is we won’t have a major supply disruption from Russia and I’m focusing more on what China and Asia’s reopening means overall.”

Comments