How the world deals with Alzheimer’s and dementia — in charts

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The small, well-tended village of Hogeweyk, 15km south of Amsterdam, would be unremarkable were it not for the fact that its entire population has late-stage dementia.

Residents go about their business as in any run-of-the-mill Dutch neighbourhood: they might grab a pastry from a baker, go to the barber and shop for groceries at the supermarket.

Except here, the baker and the butcher are geriatric nurses and specialists trained to deal with the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, which can manifest themselves as disorientation and occasionally aggressive behaviour.

There are a handful of such places scattered round the world, though they represent a drop in the ocean — Hogeweyk is home to a mere 152 residents among the 50m sufferers worldwide.

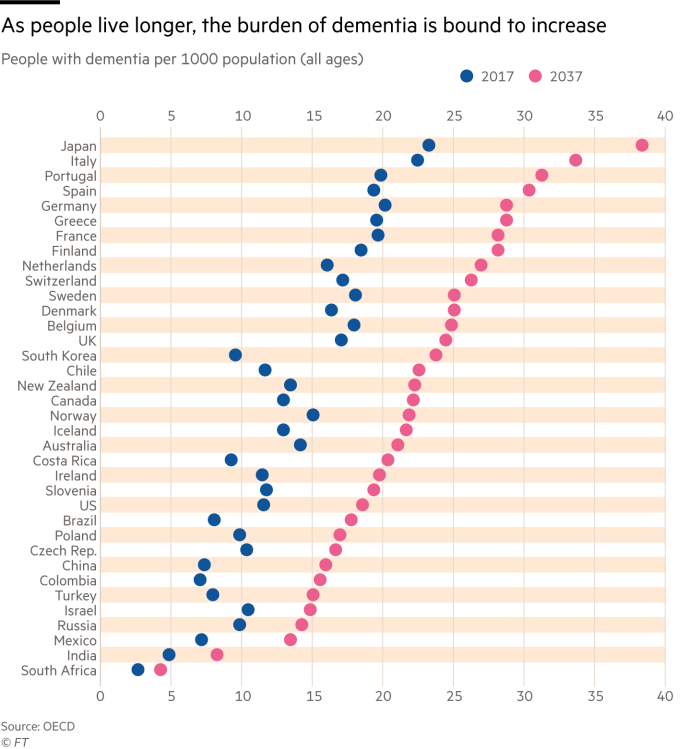

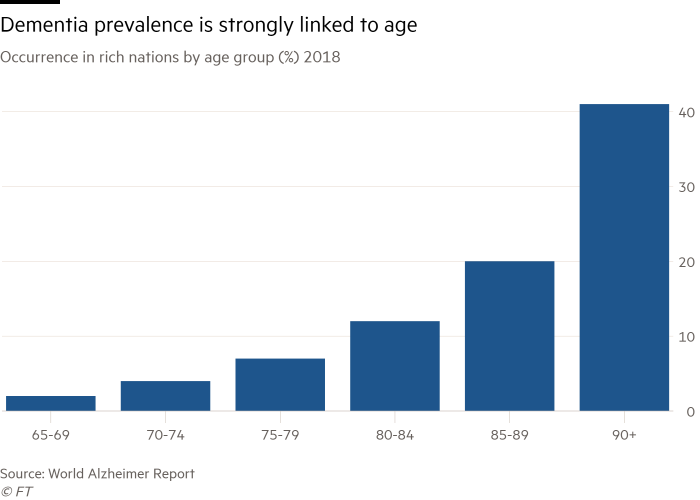

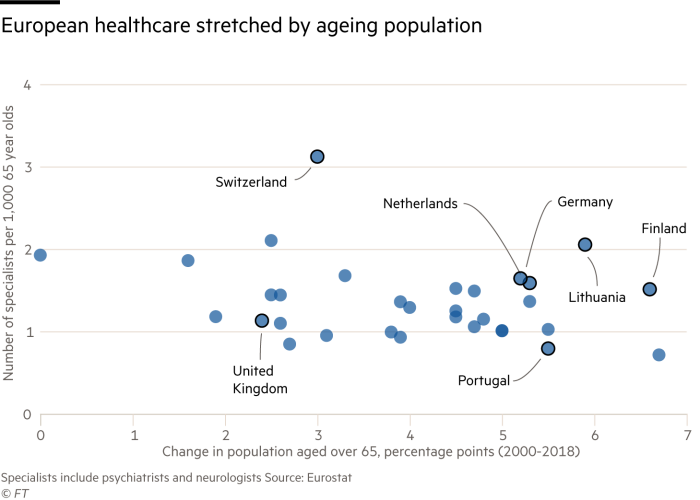

Rapidly ageing populations pose a huge challenge to society, governments and public services. Older populations put an immense strain on healthcare expenditure, and the financial costs of dementia are large and growing.

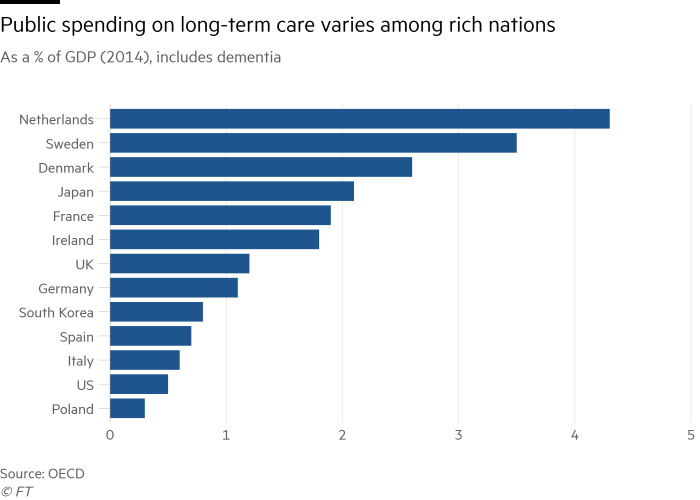

According to the most recent statistics, spending on long-term conditions such as Alzheimer’s varies widely between rich nations, from 4.3 per cent of national income in the Netherlands to 0.3 per cent in Poland.

The variation is much greater than in health spending in general and reflects large differences in the provision of care, from formal to informal — the kind provided by family, friends and the wider community. The costs attached to informal care represent about 40 per cent of the total worldwide cost of dementia.

On top of the financial cost — which those unable to find full-time work because of their caring duties feel markedly — looking after a person with dementia is mentally and physically taxing. Informal carers have a 20 per cent higher prevalence of mental health problems than non-carers, according to the OECD.

Health ministers from G7 countries have identified this group as a priority. Austria, for example, now offers respite holiday care programmes, which allow carers to relax with the assurance that someone else is looking after their loved ones.

Yet only 19 of the OECD’s 36 member countries offer some form of paid leave for informal carers.

Although many people with dementia prefer to live at home, when this is not possible they are placed in care facilities: about 70 per cent of nursing home residents have a cognitive impairment.

The OECD has pointed out that “the vast majority of long-term care facilities remain poorly designed for people with dementia”. According to the Paris-based group, staff are severely undertrained: on average, only 12 hours of tuition at medical school are dedicated to dementia care.

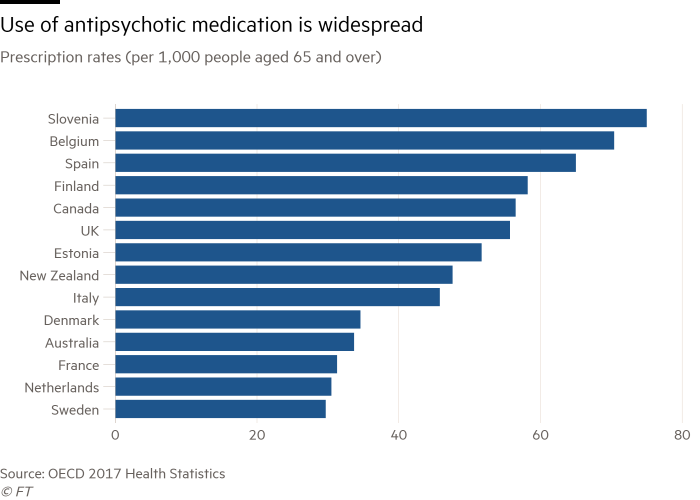

This can result in an over-reliance on antipsychotic medications to treat behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Antipsychotic usage increased by a third between 2011 and 2015, despite “widespread clinical agreement that antipsychotic medications should not be used to manage most difficult behaviour in dementia”, says Elina Suzuki, author of the OECD report.

“They can increase health risks, restrict autonomy and do not reflect a person-centred care approach,” she adds.

Meanwhile, a shortage of qualified medical specialists is forcing governments to relax restrictive immigration policies and change public health recruitment models.

As part of Japan’s “Orange plan” — a package of measures to tackle dementia — by 2020 the country plans to recruit 10,000 foreign interns in its nursing care sector. The first group of 300 trainees arrived from Vietnam just over two years ago.

Germany is having to look beyond the EU to recruit geriatric nurses and has recently signed agreements with the Philippines and Sri Lanka to plug the gap.

As countries grope for new ways to deal with the rise of dementia, many remain ill-prepared for the consequences of ageing. In the few small-scale villages like Hogeweyk, a vacancy only becomes available when a resident passes away.

Comments