Investors pump trillions of dollars a day into ultra-safe Fed facility

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Trillions of dollars each day are gushing into a Federal Reserve facility designed to mop up excess cash in the financial system, showing how many ultra-safe investment funds are avoiding volatile US government debt markets even as interest rates rise.

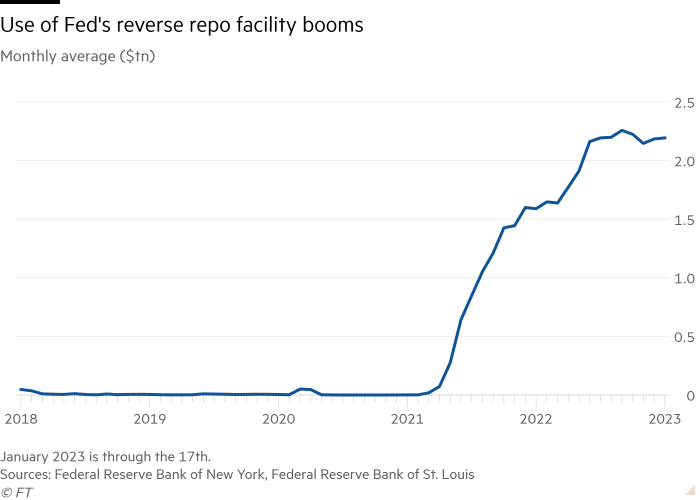

Investors this month are stashing an average $2.2tn a day in the Fed’s reverse repo facility, where investors can earn a set interest rate for parking funds overnight. That is down from a record $2.6tn on the last trading day of 2022, but above last year’s average of $2tn. Before March 2021, usage was typically just a few billion dollars a day.

The heavy use of the Fed’s reverse repo facility in recent months has confounded central bank officials and private analysts, who expected money market funds to deploy cash to buy up short-term US government debt now that it offers higher yields and because the central bank is leaving more government bonds on the market for investors to purchase as it winds down its balance sheet.

US government money market funds, which manage almost $4tn in assets, seek to maintain a fixed price by holding short-term Treasuries known as “bills” or by stashing cash in other ultra-safe vehicles such as the Fed facility. Higher levels of volatility in the Treasury bill market, prompted by regular swings in expectations for the Fed’s monetary policy, have boosted the allure of parking cash with the central bank, which in addition to being a risk-free investment provides a predictable level of returns.

“[Reverse repo] continues to be a no-brainer for money market funds,” said Peter Crane, president of Crane Data, which focuses on money market funds. “No one wants to buy anything longer than a day in case they’re wrong, in case the Fed changes directions.”

Fed officials thought the unwinding of the central bank’s balance sheet, which began last summer, would cause reverse repo usage to fall, a view expressed in minutes from six of its eight Federal Open Market Committee meetings last year. The idea is that with more Treasuries in the market offering better yields, investors would deploy their cash to purchase them, ultimately causing the amount parked at the facility to fall. However, that trend has yet to materialise.

“I would have expected the balance sheet runoff to have had a larger effect, that the market would have needed the cash that was in the [reverse repo] to fund the securities coming in the market from balance sheet runoff. But the market hasn’t really needed that much cash,” said Scott Skyrm, a repo market specialist at Curvature Securities.

The Treasury department too has played a role in promoting reverse repo by cutting its use of short-term borrowing through bills, which can have maturities as short as a few days or as long as a year.

While Washington’s aim was to lower its interest bill by extending its average repayment schedule, the shift has left money market funds and others with fewer short-term safe assets to buy — and in the process helped push yields on some super-short dated debt below the 4.3 per cent on offer from the RRP.

“Maybe if we had just maintained assets last year it wouldn’t have been as big of a deal, but because there was a lot of excess allocation into cash to avoid what was going on in the equity and fixed income markets, you had short-term Treasury rates well under the reverse repo rate, which is supposed to be the floor in the market,” said Deborah Cunningham, chief investment officer for global liquidity markets at Federated Hermes, a large money market fund manager.

Another reason for the increased use of reverse repo, analysts say, is that many investors, who cannot directly access the reverse repo facility, are still preferring to place excess cash in money market funds rather than in savings accounts offered by banks.

Usage of reverse repo could actually come down this year, if banks begin offering higher interest rates on savings accounts. While JPMorgan recently warned it might soon raise deposit rates, still-low bank rates are not yet tempting savers out of the better-yielding, low-risk money market offerings.

“I think at some point, we’re going to see banks probably start to offer more for deposits. But we’re not there yet,” said Tom Simons, money market economist at Jefferies.

Comments