Ahead of the Olympics, how sport and watches became indivisible

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Beijing Olympics, 2008. The 100-metre men’s butterfly final. US swimmer Michael Phelps is chasing his seventh gold medal of the games. Victory will put him level with fellow American Mark Spitz as the joint record-holder for winning the most gold medals in a single Olympics. Spitz had set the bar 36 years previously, in Munich in 1972, and Phelps’ effort to surpass him is one of the defining narratives of the games.

He is up against Milorad Cavic, an old rival. The Serbian swimmer has said ahead of the event that it will be good for their sport and the Olympics for the American not to break the record — provocative trash-talking to rile Phelps. Cavic also has time on his side: he won his semi-final in 50.92s; Phelps won his in 50.97s.

The crowd cheers for Cavic when they emerge from the locker room, but it roars for Phelps as the swimmers take to the blocks. Cavic starts well, leads for the first 50 metres. At the turn, Cavic is clearly ahead, Phelps behind by nearly half a second.

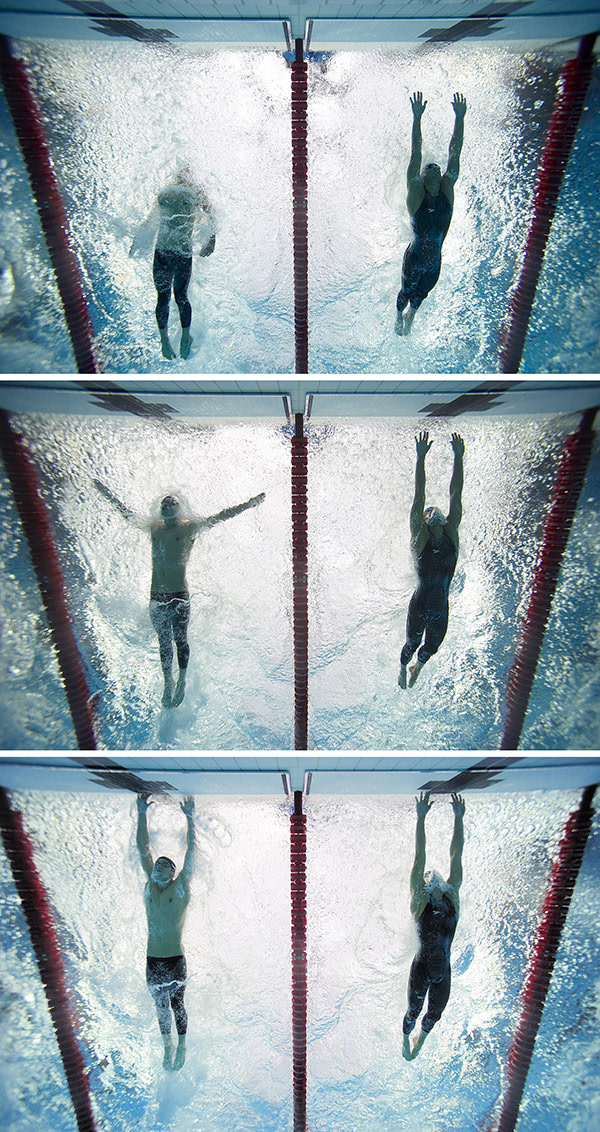

The swimmers approach the finish and the shouts and whistles from the crowd roar louder. Phelps has made up the gap but it is impossible to see who is ahead. Cavic looks like he is about to ruin Phelps’ dream.

As they push to the wall, it seems Cavic has pipped the American to the gold medal and blocked him from matching the record. But the electronic pads that the swimmers must touch to finish a race tell a different story. Within seconds, the result flashes up on the screen: Phelps wins in 50.58s, a new Olympic record — ahead of Cavic by 0.01s.

Omega, the Swiss watchmaker and official timekeeper of the Olympics, developed those touchpads. The full results beamed to televisions around the world — alongside Omega’s logo — were supplied by the company, too. Watchmaking and sports are, today, inseparable — and in ways few realise.

The association of sports and watches has an unimpeachable logic: the winner of a race depends on the time taken, and time is the very purpose of watches. But beyond that, sports have become an essential showcase for the watch industry, from demonstrating the technical prowess of a brand to ensuring it is associated in the public’s mind with a marquee event and its star athletes.

Omega became the first official timekeeper to the Olympics in 1932, when the games were held in Los Angeles. Until they became involved, every official would use their own stopwatch, says Alain Zobrist, chief executive of Swiss Timing, the unit which oversees sports timing and data handling technologies at the Swatch Group.

For their first games, Omega sent 30 high-precision chronographs able to capture results within a 10th of a second — and a watchmaker for repairs.

Technology has evolved beyond watches, and indeed the needs of sport have pushed the development of new ideas and machines. “Magic Eye”, the first photo-finish camera, was introduced at the 1948 games in London. It was developed by the British Race Finish Recording Company which worked with Omega’s timing devices. In the final of the men’s 100m that year, when Americans Harrison Dillard and Barney Ewell both clocked 10.3 seconds, the camera revealed that Dillard had won.

In 1968 in Mexico City, the first generation of touchpads were used, and at the Los Angeles games in 1984, Omega launched the first false-start detection devices in athletics. Today, Omega’s role has changed beyond recognition. Mr Zobrist neatly sums it up: “It’s the start and the stop of a race — and everything in between.” To fulfil its function at the Rio games in August, the company will send 480 timekeepers, deploy 450 tonnes of material and roll out a little more than 200km of cable and optical fibre.

Omega and the International Olympic Committee do not disclose the value of their deal.

Record keeping in its broadest sense now involves every measurement tool, from tracking scores and relaying data such as stroke speed and distance on the golf course — a new Olympic sport this year — to gauging the accuracy of an archer’s shot at the target. Mr Zobrist says the company designs and produces all of the products it uses, from the photo-finish cameras to the electronic starting pistols. “We have a lot more software engineers,” he says.

The touchpads used in swimming spew out the results within milliseconds. Mr Zobrist says the devices are designed to respond only when hit by sufficient pressure so that it is clear the impact is from a swimmer pushing through rather than by a wave caused by the athletes in the water. This, he says, is why he is sure that Phelps beat Cavic in Beijing.

. . .

Another watch brand with a long pedigree in sports, TAG Heuer, is also on the cusp of a new era. At a glitzy launch event in late April, the company revealed its latest big bet: it has now signed on to be the first official timekeeper and watch of the Premier League.

The company, part of the LVMH group, has been involved in sporting events ranging from Formula One to the London Marathon. This time it has enlisted the help of Leicester City Football Club manager Claudio Ranieri. He was just about to lead his team to the most unlikely win in sporting history, victory in the English Premier League. Leicester had started the season with odds of 5,000/1.

The absence of a watch sponsor would seem strange for such a global business whose clubs had a record revenue of £3.4bn in the 2014-15 season, according to the annual Football Money League study by Deloitte, the professional services firm. Football is currently rather low-tech in its refereeing. There is no standardisation of devices; officials use their own watches — some are analogue, some are digital — and a pencil and notebook to keep track.

Mike Riley, a former Premier League referee who now heads the body that represents officials, says he has worked with the company to develop a bespoke version of its Connected smartwatch all referees will find easy to use from next season. Among the innovations are a heart-rate monitor and a system that will mean officials can refer to standardised data when challenged by players or team managers over how much extra time must be added to a match because of substitutions, injuries and yellow or red cards.

“In Premier League football, there are probably more incidents that appear from 90 minutes to the end than occur in any 15-minute period of the game,” he says. He hopes that this new device will help limit controversy.

TAG Heuer’s move into football — it is also official timekeeper of this summer’s Copa América — is being driven from the top of the company by Jean-Claude Biver, head of LVMH’s watch group and TAG’s chief executive.

Before joining LVMH, Mr Biver was best known in the watch world for having turned round Hublot. The brand was in the doldrums when he took it over in 2004 but after increasing turnover tenfold in four years, he sold it to LVMH in 2008. One tactic that was essential to reviving Hublot was associating it with sports, including Formula One and especially football. At the time, Mr Biver says, no one was bothering with football because they saw it as too “popular” and not exclusive enough for luxury business.

However, he says, “We saw the money going into football — and the money watching football,” referring to a new class of wealthy fan. In 2006, according to Deloitte, the top 20 clubs in the world had combined revenues of €3bn; this year they were €6.6bn.

He says the company started small, aligning with the Swiss national football team. Then it built further, working with the European Championship, then the World Cup, Manchester United and Chelsea. They also partnered with individuals including Pelé, Diego Maradona and José Mourinho, the former Chelsea manager who took over at Manchester United last month.

The day after Leicester City were crowned Premier League champions, Mr Ranieri joined TAG’s ranks as a brand ambassador.

. . .

Watch companies and sports bodies do not disclose the value of these deals, so calculating a precise return on investment is not easy. But in terms of brand awareness, it is hard to find a more useful tool.

Research by Digital Luxury Group, a consultancy, showed the gap in “global interest”, measured by the number of online searches, between Rolex and nearest rival Omega had shortened by 2012: Rolex was ahead by 8.4 percentage points in 2009 but only 2.9 points in 2012. Omega was enjoying the brand enhancement from its deals with the London 2012 Olympics and the James Bond film Skyfall.

That December, Rolex signed a 10-year contract with Formula One to be its official timepiece. Some observers believe the company’s swoop on F1 was to counter Omega’s surge. “My guess is that they knew Formula One would have a major impact if, say, TAG Heuer or Omega or one of the other competitors had been able to grab the spot,” says David Sadigh, DLG’s chief executive. “Most of these moves are made in a defensive way and to prevent the competition from becoming too popular.”

Three years on, DLG’s research indicates Rolex has stretched the gap in global interest to double digits over Omega. Its most recent World Watch Report, published last year, showed Rolex taking 22 per cent of global interest, with Omega trailing in second on 12 per cent, a wider gap than in 2009. Mr Sadigh says it is impossible, however, to credit that entire shift to the Formula One relationship, particularly given the multiple sports relationships that watch brands have.

After 30 years with the McLaren team, TAG Heuer signed a deal with Red Bull Racing at the beginning of this season. Hublot works with Ferrari; Richard Mille signed deals with McLaren and Haas at the beginning of this season; Oris has worked with Williams since 2003. A number of drivers have their own watch deals.

The challenge for brands is to secure what Mr Sadigh calls the “worldwide channel”. In F1, with Rolex in pole position, others are left to form individual partnerships to gain traction. The danger for the companies behind these individual partnerships is that they feed the principal sponsor, he says. “The brand that gets control of the worldwide channel has a big competitive advantage over the others because the others risk cannibalisation.”

When Red Bull driver Max Verstappen won his first Grand Prix on May 15 this year, making the 18-year-old the youngest race winner, TAG made sure its ads with him appeared worldwide, and it will use him at events. It now has a new star around which to work.

. . .

There are always risks, however, when brands associate themselves with athletes or a sporting competition: a star may be caught doping or the sport itself might fall into disrepute, as witnessed by the corruption scandal which has descended on Fifa, football’s governing body. These are, of course, bad for the brand in the short term, but companies have tended to move fast to disassociate themselves from the controversy. Nike has not felt lasting damage from its relationship with disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong.

The real danger for the companies is if their technology goes wrong. Watch brands are staking their essential credibility when a swimmer dives into the pool or a sprinter breaks out of the blocks: they need to be right, to the millisecond, every single time. When an athlete competes, it is not just themselves they are testing.

Comments