Pension schemes’ rush for cash shakes UK corporate debt

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

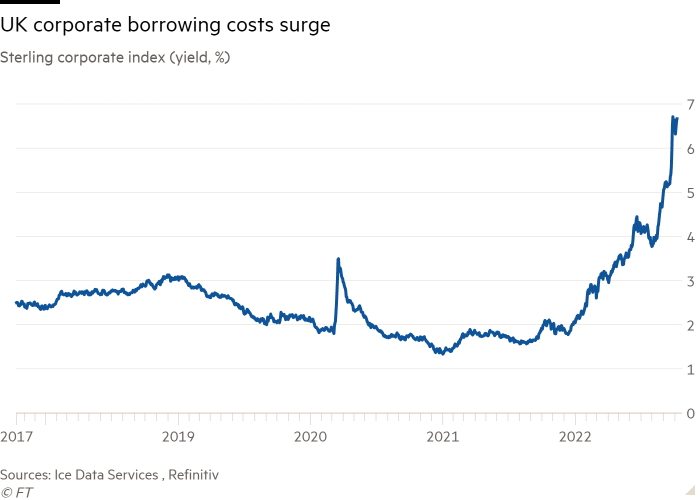

A rush for cash by UK pension funds has weakened the already shaky sterling-denominated corporate debt market and pushed up borrowing costs for companies across the country.

UK government bonds fell sharply in price last month as investors recoiled at chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s plans for unfunded tax cuts, with the debt remaining under pressure in the early days of October. Pension funds have been forced to sell more gilts to maintain their hedged positions, forming a spiral that the Bank of England intervened to halt.

But pension schemes also offloaded corporate debt in sterling during this volatile episode. Fund managers say this knocked assets including bonds for companies such as Virgin Media and Rolls-Royce.

“What you’re seeing in the corporate bond market is a fire sale,” said Paola Binns, a sterling corporate bond portfolio manager at Royal London Asset Management.

This means investors demand a higher return for holding British companies’ debt. “You had this before, with Brexit — UK borrowers were having to pay a premium to access corporate bond markets. It’s coming back now,” said Binns. “The government will say that interest rates are going up everywhere but they are going up much more aggressively in the UK than anywhere else.”

To ease the pressure, the BoE stepped up its support for pension schemes on Monday by expanding the range of collateral that could be pledged at its new short-term funding facility. Among the assets that will be accepted are UK corporate bonds.

“This should reduce the amount of forced sales in these markets and so reduce contagion,” said Antoine Bouvet, a rates strategist at ING.

By expanding the type of collateral to some sterling corporate bonds, the measure could support pension schemes still in need of cash, having a “nice trickle down effect”, said Simon Matthews, a senior portfolio manager at Neuberger Berman.

Binns added that prices in sterling-denominated bonds improved at the open on Monday but that it was unclear how the measure would play out. As of Friday’s close, the average yield on an Ice Data Services index of high-grade corporate bonds denominated in sterling had risen to 6.7 per cent from 5.6 per cent before the “mini” Budget.

Supermarket group Iceland, restaurant owner Boparan and Bracken, the owner of specialist mortgage provider Together, are among the businesses whose already high debt yields have shot higher since the “mini” Budget. Iceland’s bonds maturing in 2025 are now trading with a yield of 16.8 per cent, up from 15.8 per cent before Kwarteng’s September 23 speech. Yields rise when prices fall.

The yield on a sterling-denominated Rolls-Royce bond maturing in 2026 shot 2 percentage points higher after the “mini” Budget to over 10 per cent, and has stayed higher. Dollar debt has fared better; a Rolls-Royce dollar bond is trading at a similar level to before Kwarteng’s intervention.

In future, international businesses like engineering company Rolls-Royce could seek to plug funding gaps by borrowing in other markets, said Matthews, which would weaken trading in the sterling market further.

The UK corporate debt market is already small compared with Europe’s, and few banks have dedicated sterling trading desks, making this a tricky market for investors to navigate. Some had trimmed exposure well before the government released its new fiscal plans.

“Lots of investors have turned their backs on the sterling market,” said Tatjana Greil Castro, co-head of public markets at Muzinich & Co, a fixed-income asset manager. “Our exposure is naturally dwindling and we’re happy to run it down to zero”.

Lack of demand means it is “trading by appointment only on vast swaths of sterling high-yield”, said Matthews. “[Demand] is bordering on pathetic. It was bad before the Budget but this has made it even worse.”

This will push borrowing costs higher and will hit mid-cap companies that do much of their business in the UK harder than international companies, which can seek funding in euro or dollar-denominated debt, investors say. “It’s a real issue for companies with revenues in sterling not being able to come to market in euros and dollars,” added Greil Castro.

One consolation is that few businesses have immediate borrowing needs, after they secured capital in recent years when interest rates were low. That allows time for the UK economy to grow before many businesses seek to refinance debt.

But the prospect of a longer, more protracted recession in the UK than elsewhere in Europe will probably mean investors keep demanding higher returns, hurting business investment and Prime Minister Liz Truss’s plans to grow the UK economy, said Binns.

“For businesses, your margins are getting squeezed while your borrowing costs go up. So any liquidity that you have, you’re just going to hold back and manage in a more efficient way. You’re not going to be expanding your business,” she added.

Additional reporting by Robert Smith

Comments