Emi Eu of STPI is a hometown hero in Singapore

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Richard Deacon constructed paper towers inspired by Singapore’s public housing. Rirkrit Tiravanija mashed metal foil on to large paper sheets to make circular “time portals”. Haegue Yang sprayed rice and spices on to pulp to create textured landscapes.

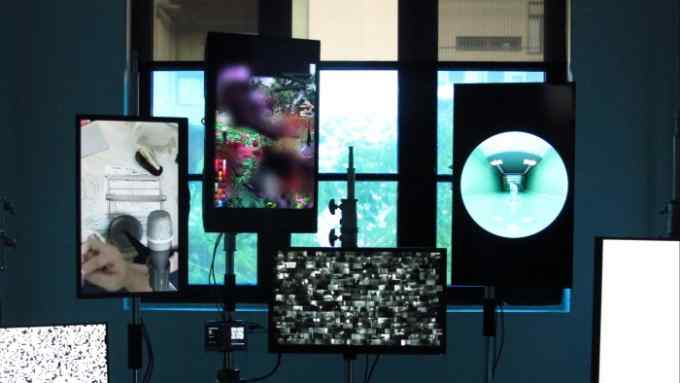

The artists created these works during their residencies at STPI Creative Workshop & Gallery in Singapore, a contemporary art gallery that specialises in experimentation in the mediums of print and paper. At STPI, they were supported by an in-house team of master printers and also had access to a state of the art printmaking facility and paper mill.

STPI has hosted 125 artists since 2002. “Spice paper, cement paper, copper paper . . . We’ve had all kinds,” says Emi Eu, STPI’s Korea-born executive director, who has been at the organisation since 2001. She is credited with building STPI’s critical reputation at home and abroad.

STPI began as a state-led initiative to kick-start the local arts ecosystem, with training up local master printers as its primary goal. Now it champions innovations in the field of printmaking; owns a commercial gallery that participates in top global art fairs; and runs its own boutique fair. Called SEA Focus, it features contemporary art from south-east Asia and its fifth edition (January 6-15) takes place at portside art cluster Tanjong Pagar Distripark, with offerings from 25 galleries in a flowing, boothless format.

Eu had a cosmopolitan upbringing. She lived with her father’s family in Seoul as a child. When she was 13, she moved to New York to live with her mother, a prominent textile historian and embroiderer. After college, through the connection of a family friend, she worked in Venice at the Galleria d’Arte Contini for four years, then studied for a masters degree at New York University in visual arts administration, during which she did an internship in the department of prints and illustrated books at MoMA.

After she met her husband, a freelance journalist and restaurant investor, she lived between New York and Singapore, and eventually settled in the city-state in 2000. A year later, she joined STPI as one of three staff in the gallery. What’s the headcount now? “Forty-eight. Can you believe it? When I first joined, I was the youngest. Now I look around and I’m the oldest!” She effectively took the reins of STPI when its founder, American printmaker Kenneth Tyler, left a few months after the opening because of operational disagreements. (STPI was formerly known as the Singapore Tyler Print Institute.)

There is no hard and fast rule by which she selects the artists for the residency, which offers up to five weeks’ stay. First, she gets to know their practice and has to feel confident that they can manage a project with 15 people waiting to receive their instructions. This is why STPI started inviting mid-career artists.

She is candid about the unevenness of the outcomes in the residency programme, but technical innovation isn’t STPI’s only aim. “Maybe for the south-east Asian artists, some didn’t produce visually groundbreaking work. But for many of them, it was an important starting point. When we began the residency programme in 2002, in Singapore, let alone the region, there were no other residencies,” she says. “So every project has a meaning.” Besides opening up possibilities for south-east Asian artists, she adds that STPI has helped to create a regional market for mid-range works on paper.

STPI’s reputation has grown organically. Artists who attended the residency introduced other artists, and collectors and museums took notice. MoMA came to acquire works. In 2013, after seven years of applying for a spot, STPI became the first Singapore gallery to participate in Art Basel; now it is the only one to exhibit in all three of the fair’s locations.

STPI is able to be ambitious in its programming and where it shows because of hefty government support. Part of the trifecta of flagship visual arts institutions in Singapore, which also includes the Singapore Art Museum and National Gallery Singapore, STPI received S$5.1mn (US$3.8mn) in government grants in the financial year ending March 2022. (Its operating budget for the year was S$8.4mn.)

While SEA Focus has been the only art fair in the city during Singapore Art Week for the past four years, after Art Stage Singapore was suddenly cancelled in 2019, this January a new juggernaut is in town: Art SG, with more than 150 galleries, intended to be south-east Asia’s largest fair. Eu thinks they are complementary: “SEA Focus is not a protagonist, we are more behind the scenes, a conduit for the region’s galleries and non-profits. We offer them a platform. Art SG is about connecting galleries to buyers, which is an integral part of any ecosystem.”

This year, SEA Focus is launching a projects section called Collaborations. One of the presenting artists is Danh Vo, who will be supported by Vitamin Creative Space and M Art Foundation, both from China. The Berlin-based artist will realise a work that explores his passion for gardening.

Eu, who has overseen STPI’s transformation, hopes that it continues to grow with the times. “I want it to evolve and not be put in any box,” she says. “I feel like I’ve done my job to bring STPI to where it is now; the next thing to do is to pave the way for a new chapter.”

Comments