Collector Harry David — dreaming of Africa

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Harry David’s sleek, modern house in a leafy suburb of Athens is full of art. For nearly 10 years, the Greek Cypriot businessman has been quietly building an important collection of contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora.

“I have the bug that collectors have; I don’t think it ever eases,” says David when I visit the home he shares with his South African wife Lana de Beer in March, just before the Covid-19 lockdown shuts down most of Europe.

David, 54, is a managing partner of the international conglomerate Leventis Group founded by his great uncle, the Greek Cypriot Anastasios George Leventis, in Ghana and Nigeria in 1936. The family has long supported the arts: a foundation set up to promote the cultural heritage of Greece and Cyprus, following the death of Leventis in 1978, has provided funding to the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the British Museum in London for the display of Cypriot antiquities, among many other gifts.

But David’s personal focus is on contemporary art. “I very much want to support living African artists. I’ve spent a third of my life in Nigeria; I grew up and went to school there and I travel there every five or six weeks,” he tells me.

I have come to talk to the couple about the upcoming display of their collection at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens. Originally scheduled to start in May, the show will finally welcome visitors from September 19 following the museum’s reopening post-lockdown. Five curators, including the African-American artist Rashid Johnson and Tate curator Osei Bonsu, have selected from David’s collection, which now includes around 400 pieces. “I’m very picky when I buy. For me, it’s not about the numbers,” says David.

The idea for the show came from the centre-right government of prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, elected in July 2019. “The museum is in an old brewery which was converted to display art but it’s been sitting empty for years. When this government took office they decided that they wanted to open it to the public no matter what and they found the money to do it,” he says. “They wanted to show something out of the box and knew I was collecting works which deal with the developing world, immigration and crisis,” all themes which resonate strongly in Greece. “It was a very easy ‘yes’ from me.”

Although the couple are generous lenders to museums and exhibitions, they have never shown their collection publicly until now. Instead they live surrounded by their sculptures and paintings and welcome a steady stream of guests — fellow collectors, museum curators, artists, and other interested parties — to see it. “We host a substantial number of lunches here,” says De Beer, and “we change the installation every year.”

The current domestic display includes a massive ball of jumbled petrol tubes by Pascale Marthine Tayou, which was included in a show devoted to the Cameroonian artist at the Serpentine Sackler gallery in London in 2015.

On a wall nearby, seven masks fashioned from used oil canisters and other discarded materials by the Beninese artist Romualde Hazoumè are displayed in a vertical sequence like an African totem pole.

“Oil is a big driver of economies in Africa but it can also destroy environments; it can make lives better and it can make lives worse. So it’s a complicated conversation,” says David.

“Hazoumè always says ‘what the West has dumped in Africa, I return to the West as art’,” he adds, noting that African artists’ use of recycled materials, often born out of necessity because of a lack of art supplies, is a “common thread” running through his collection, as are works that deal with poverty, racism and social injustice.

An example is upstairs: an installation of 13 wall clocks by the Beninese artist Meschac Gaba is a study in African governance. Each clock face features a photograph of a different leader, ranging from Nelson Mandela and the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba to the Libyan despot Muammar Ghaddafi. Near the clocks, a cast-bronze sculpture of an African mermaid by the Kenya-born artist Wangechi Mutu sits regally atop an enormous plinth. “She is going to a show in Johannesburg; she leaves in two days,” says David.

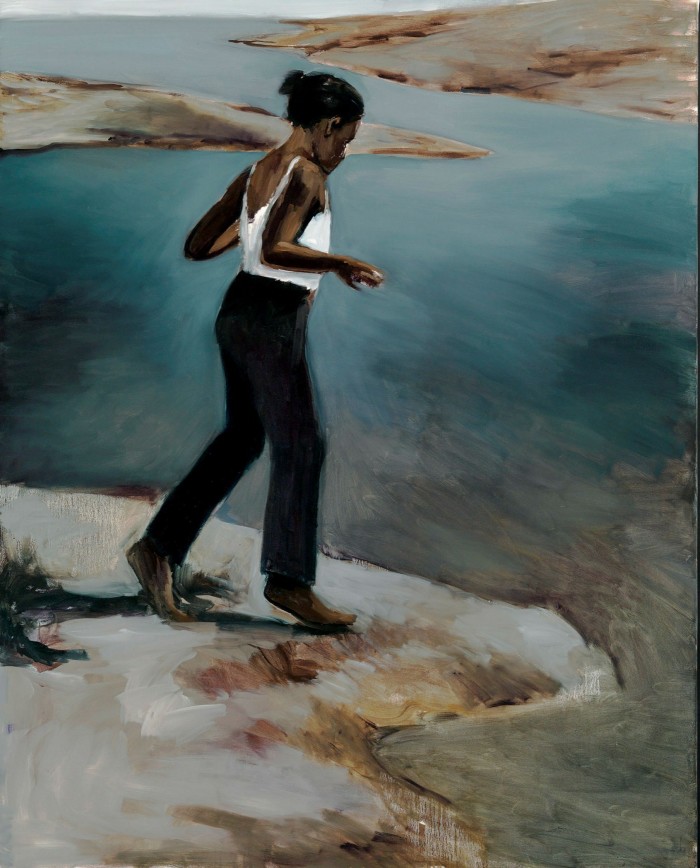

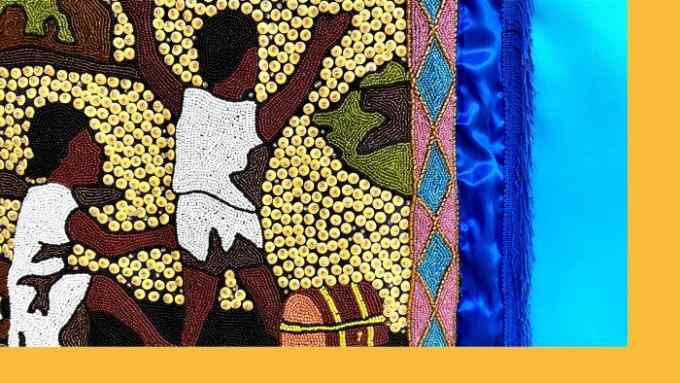

Mutu is one of the artists David and De Beer collect in depth. “I’ve been buying her work for around 15 years,” says David. Others include the South African/Malawian artist Billie Zangewa, who makes sumptuous silk wall hangings; one showing her naked lover sprawled on a bed holding a bottle of wine hangs above the Davids’ own bed. Other artists collected by the couple in depth are the Nigerian Taiye Idahor, the African-Americans Hank Willis Thomas, Mickalene Thomas and Rashid Johnson as well as the British artists Chris Ofili and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

Although interest in contemporary art from Africa has surged in recent years, there are still relatively few collectors who have amassed significant holdings in the field. One is Jochen Zeitz, former chairman of the sportswear company Puma, who has given his art on long-term loan to the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art in Cape Town which opened in 2017. Another is Jean Pigozzi, a tech investor and heir to a French motor fortune, who assembled his collection without once visiting Africa himself.

David and De Beer take a different approach, visiting artist studios, private collectors and galleries in Africa, sometimes with Tate’s Africa Acquisitions Committee, which David joined in 2013 and De Beer in 2019. “With Tate, we’ve been to South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria and the Netherlands where many African artists now live. We’re all learning together because there’s still remarkably little research on contemporary African art.”

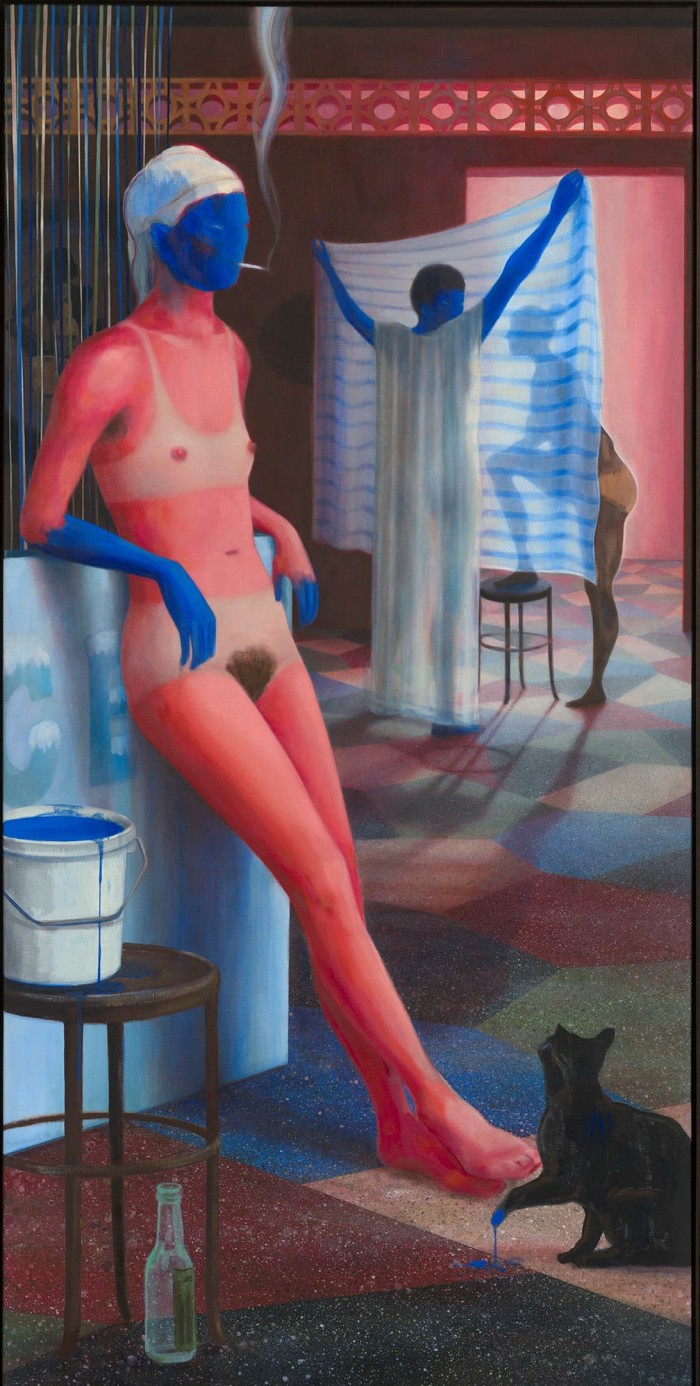

Because of their association with Tate, the couple have donated a silk wall-hanging by Billie Zangewa to the gallery as well as a painting by the South African Lisa Brice and one by the Kenyan artist Michael Armitage. Another painting by Armitage has gone to the National Galleries of Scotland “because they asked for it”, says David.

He welcomes museums’ rising interest in African art, but is wary of market hype. “Of course, it can be good for African artists; many of them want to break into the mainstream but sometimes it’s done at the wrong pace. I try not to get carried away by it. That is a big trap.”

A case in point is the Ghanian painter Amoako Boafo, who exploded on to the art scene last December with a small show at the Rubell Museum in Miami and a presentation on the stand of Chicago dealer Mariane Ibrahim at Art Basel Miami Beach where the works were on sale for up to $45,000. Just two months later, a 2019 painting by Boafo was offered at auction by Phillips London with an estimate of £30,000 to £50,000. It sold for £675,000 with fees, an astounding price for an artist with no prior auction history.

This suggests that market speculators are buying and rapidly reselling the artist’s work. The danger is that speculators can dump an artist’s work en masse as quickly as they embrace him, sending prices for the work crashing, a catastrophe for any young artist. “Boafo is an interesting painter but I’m not convinced that what is happening to his market is either correct or healthy and I’m not sure I necessarily want his work. Nobody knew Boafo a year ago. Why is his work suddenly worth several hundred thousand dollars? It’s insane,” says David.

So what does the couple intend to do with their collection in the future? Perhaps open a private museum for it? “I don’t think we need to do that to share the collection. I would rather do something else like help curators or artist-run spaces in Africa. We would like to support people who go and document artistic scenes on the continent; our dream is to do something substantial in Africa.”

‘Ubuntu: Five Rooms from the Harry David Art Collection’ is at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, September 19-March 18 2021, emst.gr

Comments