The big WEF question: economists v markets, who’s right on growth?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

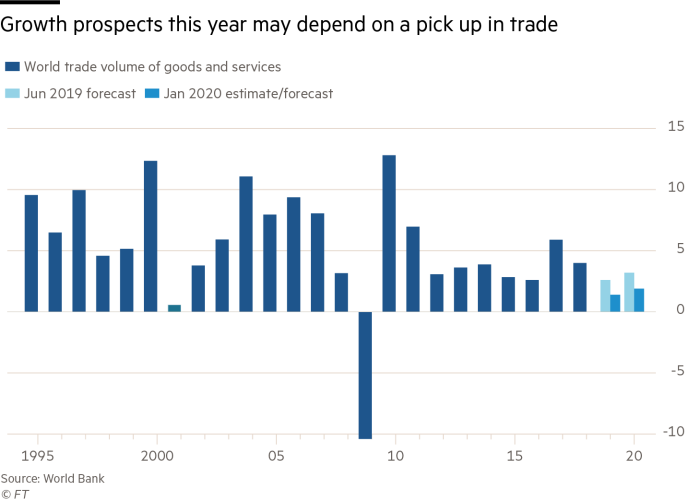

The world economy started 2020 on a positive note, fresh from a Donald Trump tweet at the end of last year signalling the US president was about to sign a limited “phase one” trade deal with China.

The agreement suggested that the year might escape 2019’s curse of ever rising trade tensions. If so, 2020 would be spared increasing political risks and uncertainty, with knock-on benefits for investment and trade in all continents.

This view has buoyed financial markets so far this year. The MSCI index of global equities was up more than 3 per cent in the month to the end of the first week in January.

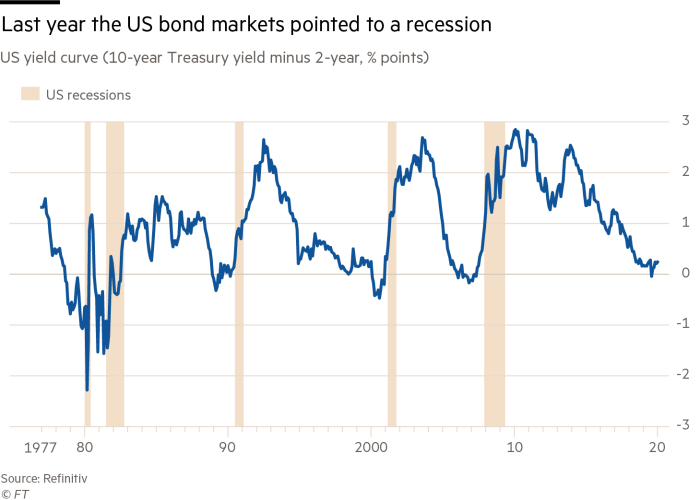

Bond prices have reflected even more optimistic thinking. Compared with last autumn, US risk-free interest rates on government bonds no longer signal a recession looming ahead.

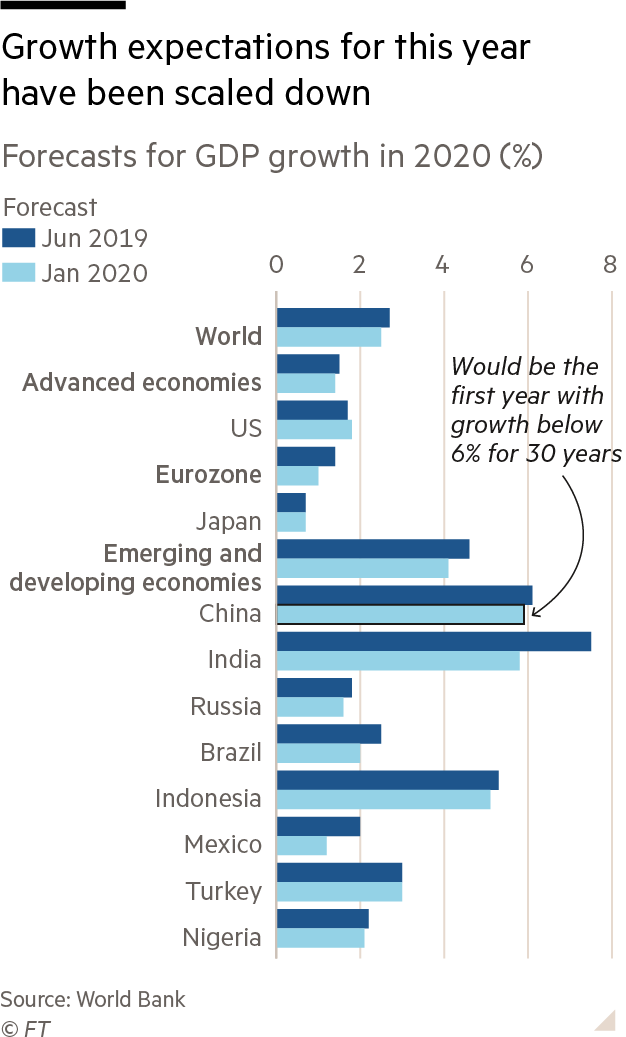

Yet this market optimism has not yet convinced economists who specialise in looking at the underlying data: they neither expected a global recession this year, nor are they now much more positive about the outlook. Economic forecasts for 2020 suggest another weak year ahead with little to no improvement from that foreseen in the autumn.

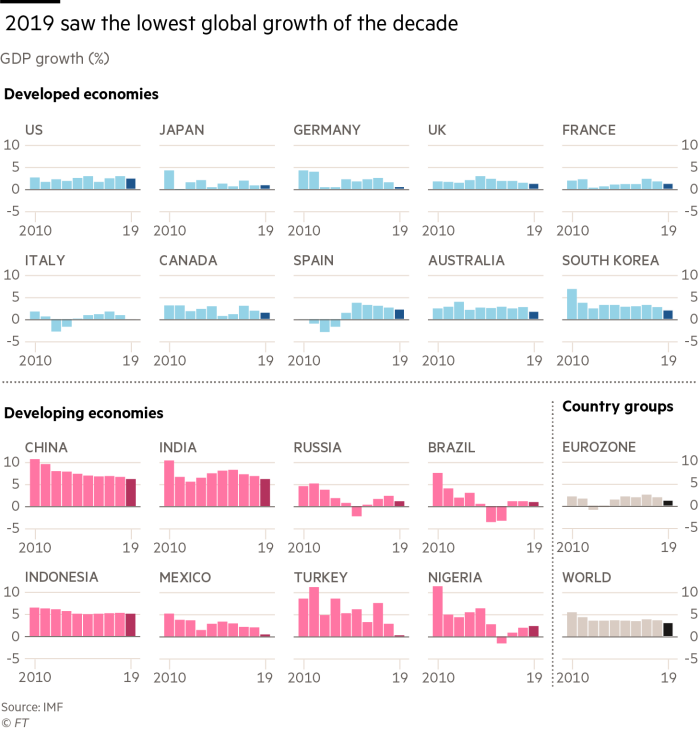

The World Bank expects, using prevailing exchange rates, global output to rise from a decade low of 2.4 per cent in 2019 to 2.5 per cent in 2020.

Something better would require, “a sustained reduction in policy uncertainty”, according to Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, the vice-president in charge of equitable growth at the World Bank.

Likewise at the consultancy Oxford Economics, the global view for 2020 is for a “steady and unspectacular” improvement.

“Limited spare capacity, the rising stock of global debt, and elevated asset prices are all likely to reduce the positive impulse from actions by policymakers,” according to Ben May, director of global macro research.

Janet Henry, global chief economist of HSBC, says: “Even though the US and China have agreed a ‘phase-one’ trade deal . . . uncertainty regarding the relationship and rising tensions in the Middle East mean that global investment is unlikely to rebound meaningfully.”

Another awkward fact is that most of the headlines for the global economy and its major players are likely to be pessimistic this year.

China, for example, is expected to post its first sub 6 per cent growth rate for 30 years with the economy gradually slowing, the US economy is slowing as the boost from the 2017 tax cuts fades, and the eurozone will struggle to expand more than 1 per cent in part caused by its exposure to global trade tensions.

In large emerging economies, the recent trends have been even more concerning. While India was the fastest-growing large economy in 2018, expanding 6.8 per cent, the World Bank marked down its estimate for 2019 to only 5 per cent and sliced almost as much off the forecast for 2020 on the back of restricted credit growth and consumer spending amid political uncertainty.

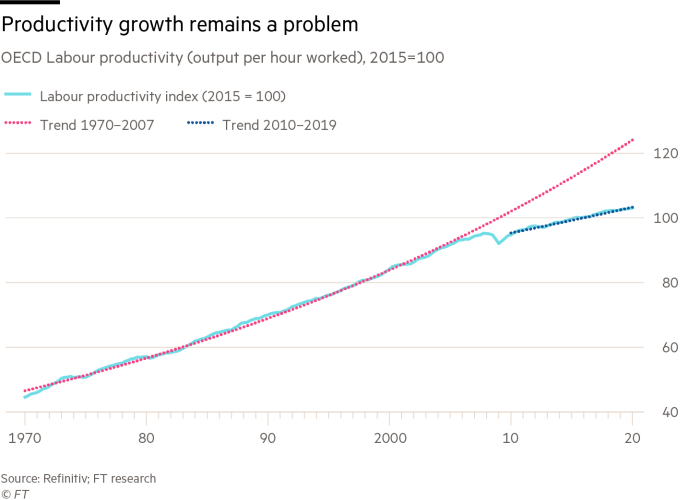

The biggest problem globally is that productivity growth is stalling almost everywhere. This implies that present-day technological advances are not enabling companies and countries to improve living standards without adding to employment or hours worked.

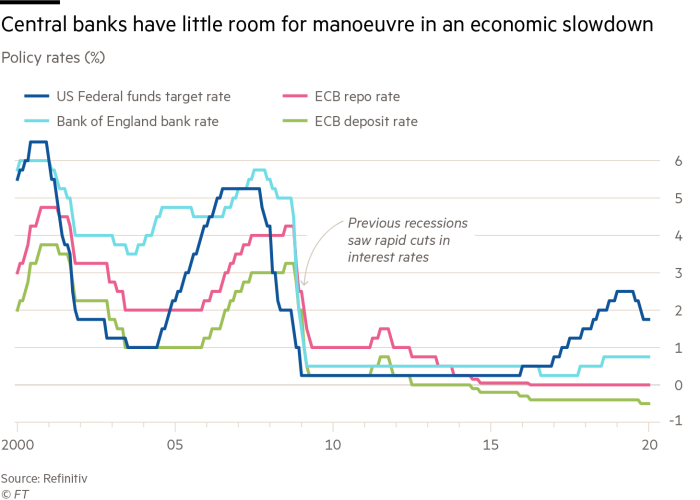

Beyond the stimulus already imparted by monetary policy easing in both the US and eurozone, central bankers past and present are now fretting that they are running out of ammunition. With interest rates still close to rock bottom more than a decade after the global financial crisis, there is a limit to what conventional and unconventional policy can do.

Eyes generally then turn to fiscal policy as the anchor of global activity, but this is stable in most economies, with the notable exceptions of the UK and the Netherlands, which are pursuing more aggressive public spending increases.

To address the deep-seated problems militating against the chances for improved growth during the rest of this decade, the World Bank has called on countries to take a number of steps to improve the way their economies are functioning.

It has recommended, for example, that they “pursue decisive reforms to bolster governance and business climate, improve tax policy, promote trade integration, and rekindle productivity growth, all while protecting vulnerable groups”.

While a period of global trade and political stability would allow countries to focus again on such bread-and-butter matters, still serious risks remain. Trade tensions might be easing with China, but a transatlantic dispute over taxation of digital companies is escalating. Efforts to find a global solution look to be in some trouble. There is no guarantee that geopolitical tensions will confine themselves to politics.

The economic year ahead looks more difficult than markets expect without the sufficient resolution of global problems to stimulate an investment-led recovery. For 2020, economists appear predictably dismal, but a year of stability could provide the foundation for better times ahead.

Comments