How Covid has raised the profiles and fortunes of India’s pharma entrepreneurs

Simply sign up to the Pharmaceuticals sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Cyrus Poonawalla was an accidental entrant to the pharmaceutical industry. The 80-year-old comes from a renowned horse-breeding family that supplied thoroughbreds for polo and racing. In the 1960s, the family also provided horses for the Indian government’s Haffkine Institute in Mumbai, which used them to make life-saving antivenoms for snake bites.

By injecting live horses with small, non-harmful quantities of snake venom, scientists could generate antibodies to be drawn and used as antidotes for people bitten by dangerous snakes, which kill tens of thousands of Indians, mostly in rural areas, each year.

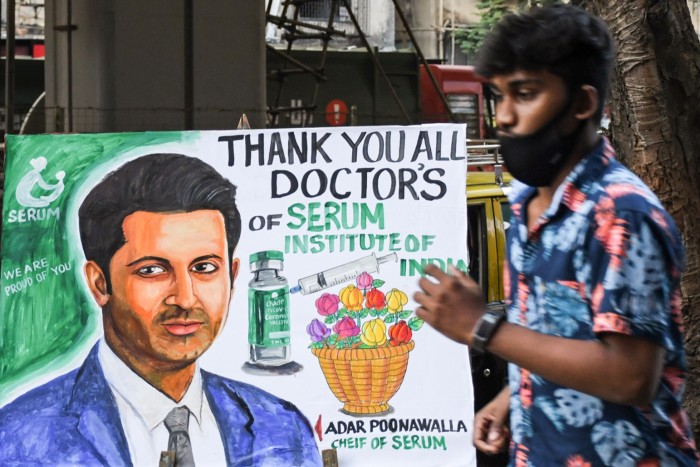

Eventually, Poonawalla started producing the anti-snake bite serum himself. “Instead of just supplying and selling the horses, my father said, ‘Why don’t we go up the value chain?’” his 40-year-old son Adar recalls. A few years later, in 1974, the newly established Serum Institute of India (SII) began local production of tetanus vaccines, which, until then, had only been available as costly and scarce imports.

“There was a national shortage and a dependence on imported vaccines,” says Adar, who is now SII’s chief executive. “My father wanted to do something for the masses, to support the government of India and their requirements at that time.”

Now the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer by volume, SII produces 1.5bn World Health Organization (WHO) approved jabs a year for diseases such as polio, diphtheria, measles, mumps and rubella for use by the public immunisation programmes of some 170 countries.

The Covid-19 pandemic, however, brought new opportunities and challenges to the company, still privately owned by the Poonawallas. Known for providing affordable paediatric vaccines to emerging markets, SII was granted the rights to make the Oxford-AstraZeneca Covid vaccine for developing countries, with the sale price capped at $3 a shot. It was a struggle to scale up production fast enough to meet demand from India and foreign buyers, such as the Covax facility backed by the WHO.

In March, as the highly contagious Delta variant fuelled a devastating wave of Covid-19 in India, prime minister Narendra Modi’s government banned Covid vaccine exports and diverted SII’s entire production to domestic use, leaving SII to explain to overseas customers why it could not deliver on its pledges.

“Everybody wanted it first — they couldn’t understand why there was such short supply,” says Adar, though he says New Delhi “had no choice”, given the ferocity of the wave of infections at the time. “The world didn’t see the horror that was happening. If they did, they would have understood sooner.”

Today, SII is producing more than 220m doses a month of Covishield — its brand of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. More than 974m Covishield jabs have been administered in India, and New Delhi is gradually allowing overseas shipments to resume. “We are going back to our commitments to export,” Adar says.

Overall, SII, which employs more than 6,000 people, sold vaccines worth $1bn in the year to March. And, although Cyrus Poonawalla was motivated originally by ideals of service to a young, impoverished nation, his entrepreneurship has generated tremendous personal wealth. According to Hurun, a Shanghai-based research company, the Poonawallas are India’s sixth-richest family, with assets of $21bn, a 74 per cent increase over last year.

The Poonawallas who come from India’s tiny Parsee community — descendants of Persian Zoroastrians who migrated to the subcontinent between the eighth and 10th centuries — are based in the western city of Pune and make little effort to hide their fortune.

They remain keen horse racers, with extensive stables, and enjoy a jet-set lifestyle, with collections of art and sports cars. In 2015, Cyrus Poonawalla bid $113m to buy a seaside mansion in Mumbai that previously housed the US consulate, in the most expensive residential property deal recorded in India. He also once tried to acquire London’s luxury Grosvenor House hotel.

But while the Poonawallas may be conspicuous in the enjoyment of their riches, they are not unique in their success. Rather, they are the most visible of a growing coterie of successful Indian pharmaceutical entrepreneurs, whose businesses — initially set up to meet India’s pressing domestic need for affordable drugs — have come of age and emerged as globally competitive medicine suppliers.

For decades, Indian drugmakers had engaged in bitter conflicts with western pharmaceutical companies over intellectual property rights and drug patents — a competition epitomised in the 1990s by Yusuf Hamied and his company Cipla’s defiant production of generic HIV/Aids drugs for Africa, much to the fury of the original producers.

But India’s 1995 adoption of more stringent patent laws to comply with World Trade Organization requirements has led to the formation of new forms of mutually beneficial partnerships between western and Indian pharmaceutical groups.

These tie-ups have come under the spotlight during the Covid-19 pandemic, as Indian entrepreneurs have struck deals with innovative western drugs companies to scale up production of sought-after vaccines and Covid drugs for many parts of the global market.

“This pandemic taught us that the Indian pharmaceutical industry is fantastically responsive,” says Murali Neelakantan, formerly general counsel at Cipla. “We can make stuff that the world needs, very quickly, at short notice. No other country in the world can do it at the scale we can.”

According to Indian government figures, the country exported more than $24bn worth of pharmaceutical products between April 2020 and March 2021, 18 per cent more than in the previous year, as global demand for drugs soared in the pandemic. Growth is expected to remain buoyant as the production and export of jabs and medicines accelerates.

“It’s very evident, with the growth we’ve been seeing over the last few years, that India will continue to be the global source for manufacturing drugs and vaccines at scale,” says Anas Rahman Junaid, managing director of Hurun India. “I haven’t seen anything that is going to put a brake to that.”

Much as India’s groundbreaking IT services industry came to symbolise the aspirations and tech prowess of a newly globalising nation in the 1990s and early 2000s, so the nation’s pharmaceutical industry shows its potential as a hub for high-tech manufacturing of sensitive products. It has also emerged as one of the country’s most significant generators of wealth.

Of India’s estimated 237 billionaires, 40 have made their fortunes from pharmaceutical companies, according to the latest Hurun India Rich List, released in September. Of the 1,000 or so Indians on Hurun’s list — for which the cut-off is assets of about $140m — 130 are in pharmaceuticals, highlighting the depth of the sector.

Other Indian healthcare entrepreneurs have prospered in the pandemic, as demand for their services surged. According to Hurun, India has seven billionaires who founded hospital chains, diagnostics labs or other healthcare services. These include Pratap Reddy, founder of Apollo Hospitals, whose family’s wealth is estimated at $2.8bn, up 169 per cent in a year, and Arvind Lal, the chair and owner of Dr Lal Pathlabs, whose family wealth is now some $2.6bn, 126 per cent higher than last year.

Lal, a pathologist by training, transformed a single pathology clinic inherited from his father in 1977 into a Bombay Stock Exchange-listed company with a network of 270 labs and 4,000 collection centres that tested about 20m patients last year.

His initial expansion came in response to high demand for his lab services, as he received samples from across Delhi and further afield. “It dawned on me that if people could send samples from other hospitals, why not set up small centres of my own where I could invite people to come and give their blood?” he recalls.

As landlords were reluctant to provide him with spaces to rent, his first collection centres were revenue-sharing arrangements — a model that proved successful. “I’d never heard the word ‘franchising’, but it was the only way of establishing a small collection centre,” he says.

Even after decades of growth, Lal believes the diagnostics industry has plenty of room to expand, as rising household incomes drive demand for quality healthcare services. “The [gross domestic product] of India will keep rising. People below the poverty line will come up, and when they have disposable income they will be able to go to a private sector [practitioner] who is adequately trained,” he says.

While previous generations of doctors relied mainly on clinical observations for diagnoses — in part because of a lack of labs — Lal says physicians now rely much more on diagnostic tests. “Medicine has become more evidence-based. A good doctor is not likely to give medicines without a test,” he says.

Covid brought challenges as demand for tests surged, but Lal says it also helped his company appreciate the potential of the diagnostics market beyond big cities and towns. “Covid has taught us how to go into the interiors of India,” he says. “We may not be able to do tests there, but we can get there, get the sample and bring it to the district [centre] to process.”

The Modi government is also trying to improve Indians’ access to healthcare, with an overhaul of long-neglected government primary healthcare centres and a three-year-old health insurance scheme that is intended to help Indians obtain tertiary care for accidents or severe illness.

While New Delhi spends only about 1 per cent of GDP on healthcare, that is expected to rise eventually to 3 per cent, moving the country closer to the 10 per cent mark in the developed world. “The Modi government has done unprecedented work in the field of healthcare,” Lal says.

India’s pioneering pharma entrepreneurs mostly began setting up their businesses in the 1970s, aided by what were notoriously weak patent laws, which allowed researchers to reverse-engineer globally patented drugs to sell at low prices to the vast domestic market. This, of course, infuriated western companies that had originally developed the medicines. “Indian pharma companies were seen as ‘pirates’ — western companies had all the intellectual property and patents, and we were stealing it from them,” says Neelakantan.

As Indian drugmakers expanded their research and production capacities further, they began competing directly with western groups to make generic versions of off-patent drugs for developed markets. But India’s adoption of product patent laws in 1995 opened a new chapter for the industry, as western companies came to see Indian companies not just as rivals, but as partners able to help them tap more price-sensitive emerging markets.

“Big Pharma — the innovator companies with new products — started to find Indian companies could be good partners,” says Neelakantan. “They are able to do good R&D, be effective on cost and deliver on quality.”

Partnerships between innovative foreign drug companies with cutting-edge medicines and Indian groups with large, low-cost manufacturing facilities have been crucial for Big Pharma to fend off criticism that it puts profits before patients and holds back life-saving medications from people in poor countries.

“At least in the lower-income countries, Big Pharma wants to be seen as doing good,” says Neelakantan. “But they can’t sell in these markets without Indian companies helping them. They are using Indian pharmaceuticals as an instrument, to be seen as providing affordable healthcare to the world.”

Among the emerging markets being served by such relationships are India itself, where the estimated 1.3bn population consumes some $42bn worth of medicines each year — a figure officials expect to at least triple over the next decade as incomes rise.

During the pandemic, a clutch of Indian companies — including Cipla, Pankaj Patel’s Zydus Cadila, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw’s Biocon and B Partha Saradhi Reddy’s Hetero — tied up with US pharma group Gilead Sciences to produce its antiviral drug remdesivir. This medicine was hailed early on in the Covid-19 pandemic as an important weapon against severe cases of the disease, although its efficacy has since been questioned by the WHO.

Other Indian drugmakers — such as Dilip Shanghvi’s Sun Pharma, the Murali Divi-owned Divi’s Laboratories, Manju Gupta’s Lupin and Basudeo Narain Singh’s Alkem, as well as Cipla again — began producing the antiviral favipiravir. This was developed by Japan’s Fujifilm Holdings and was granted approval in India for restricted emergency use in cases of mild to moderate Covid-19.

And, this year, US pharma giant Merck has signed voluntary licensing agreements with eight Indian companies, including Cipla, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Hetero and Sun Pharma, to make molnupiravir, an antiviral that studies suggest could cut the risk of hospitalisation and death by half if taken within five days of Covid-19 infection. As research continues, more deals are likely.

Yet, even as they prosper by manufacturing drugs developed elsewhere, some Indian entrepreneurs are trying to undertake original drug research. Family-owned Zydus Cadila, whose chair Pankaj Patel’s net worth is estimated at $6.5bn, has developed a three-dose Covid-19 vaccine for children aged 12 to 18. Though Indian drug regulators have approved the vaccine, New Delhi has yet to make the political call of whether to begin inoculations of children against Covid as part of the public jabs programme. Meanwhile, Hyderabad-based vaccine-maker Bharat Biotech has developed Covaxin, a Covid-19 vaccine that has been listed by the WHO for emergency use.

Adar Poonawalla expects drug R&D to increase steadily in India. “With wealth creation, there will be more research and you will see new molecules coming out of India,” he says. “As these companies start selling into the US and Europe, revenues are growing and they will use that to plough funds back into research and development.”

Recently, SII has been focusing on backward integration: acquiring a stake in a maker of glass vials and other materials for dispensing vaccines, as a means of avoiding future production bottlenecks for jabs that are in high demand.

Beyond improving logistics, Adar says he is looking forward to working with researchers from around the world to roll out vaccines to combat established deadly diseases for which there are still no widespread inoculation programmes. Among other projects, his company is working with the UK’s Jenner Institute — developer of the Oxford-AstraZeneca Covid vaccine — and US drugs group Novavax on a potential new malaria vaccine.

“My goal would be to be present in almost every country — including western countries — providing low-cost, high-quality products to them,” he says. “I’m obsessed with eradicating so many of these diseases, [such as] malaria, HIV and tuberculosis.”

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments