Virgil Abloh blossoms at Louis Vuitton and Rick Owens blurs boundaries. And everyone is upstaged by Karl Lagerfeld

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Virgil Abloh is thinking about organic progression at Louis Vuitton. “I want to go upwards in trajectory, not flat. I don’t want to rest on my laurels,” he said, a day before his Spring/Summer 2020 show. A boy walked past, toting a macramé bag spewing out blossoms. Abloh wasn’t wilfully punning, but did pun nonetheless — his Louis Vuitton collection was about gardening.

Which is strange, because Fendi’s on Monday was, too. It was coincidental, nothing copycat about it — those Vuitton macramé bags, patterned with some of the quatrefoil flowers that space out the LV monogram, aren’t whipped up in days. Neither is an entire square of Paris commandeered to stage an outdoor show, as Abloh did around the Place Dauphine in the historic centre of Paris, a few hundred feet from Vuitton’s studios. And Abloh’s use of gardening — or rather nature — as a metaphor was interesting. For him, it stands for diversity. “In nature, you never just see strictly one species of flower together,” he said, “except in a cornfield or something — where man has intervened.”

The theme was a neat mirror of the show he staged on Wednesday morning for Off-White, where models wandered through fields of flowers towards photographers. Abloh founded Off-White in 2012; it was named Hottest Brand of Quarter 1 of 2019 by Lyst Index, who analyse the behaviour of over 5 million online shoppers each month, to see, essentially, what they are actually searching out. At the moment, it’s Off-White — directly ahead of Gucci, Balenciaga, Valentino and Fendi. Which also touches his rabidly popular reinterpretation Vuitton where he has been men’s artistic director since spring last year.

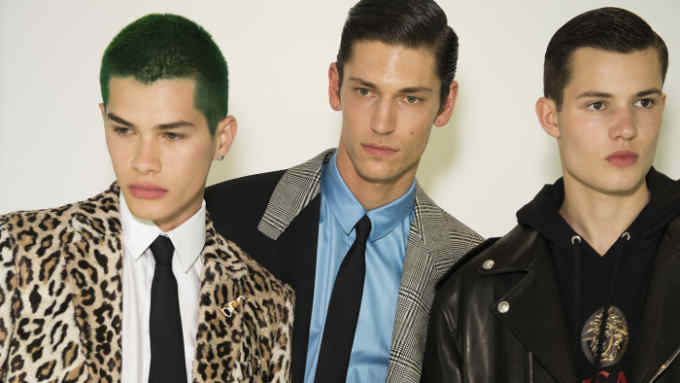

Popular and populist — Abloh’s references are easy to read and consume, as are casting choices like using as models public figures such as the musician Dev Hynes, the actor Keiynan Lonsdale and the Arsenal player Héctor Bellerín, in a rhododendron-pink crocodile hoodie. Elsewhere, there was a Louis Vuitton branded inflatable castle, and models in the finale toted logo-ed red balloons. Which made me think of Nena’s “Luftballons”, and of the movie It. It — the balloon, not the movie — links with Abloh’s continuing exploration of themes of boyhood and maturity. “Childlike creativity, curiosity — that sparks a tension for me to think about menswear,” said he.

It also links with It bags, which is what Vuitton is about. Abloh’s this time were decorated with tuffetage — an embroidery technique based on carpet tufting, it expressed the idea of something growing out of them. It was clever — especially given that the method was applied to Vuitton’s monogram and also checkered Damier patterns, in a dizzying array of shapes and sizes. Other bags, liberally blooming with flowers, were more literal. Which was mostly free from the clothes. These were some of Abloh’s most assured, least tricksy — bar the strange, kite-like bag pile-ups at the end, which seemed out-of-place and jarring next to this mostly harmonious offering.

The floral theme surrendered prints, sure, but also a delicate bouquet of colours, violet and cornflower blue and sage-green, while the use of Vuitton’s monogram flowers as floral designs in quilting patterns and those macramé totes also didn’t just link the collection to the house: it literally copyrighted it. Abloh has an idea that you can amend a design by 3 per cent to make it new — a tweak to make it fresh enough to interest, entice and sell. It’s a design philosophy but it must be music to a fashion executive’s ears. Because the bags here — which are what really sells — were barely tweaked Vuitton classics which will shift again.

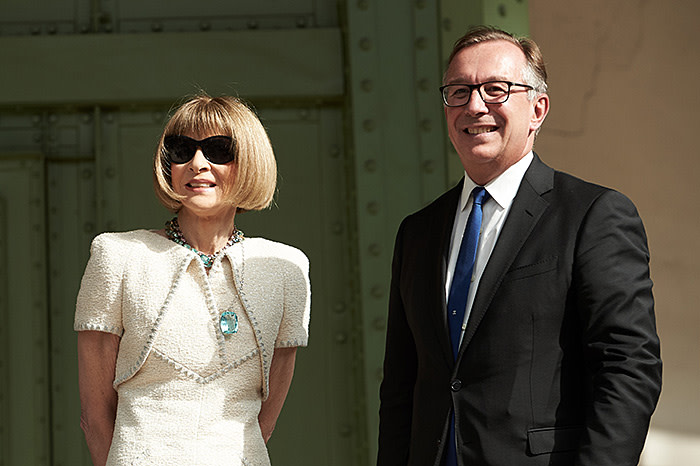

Garden shows are kind of an established industry trope, especially for spring as they spell out clear notions of renewal, growth, new beginnings. Karl Lagerfeld, the former artistic director of both Chanel and Fendi’s womenswear, staged at least half a dozen: one based on the parterre of Last Year In Marienbad; another with paper blooms that opened mechanically when “watered”. Both of those were held in the vast enclaves of the Grand Palais, where a memorial to Lagerfeld took place on Thursday evening, art directed by the opera impresario Robert Carsen in front of 3,000 guests. It was the spot where Lagerfeld’s imagination (and Chanel’s multiple millions) also recreated the Eiffel Tower and a rocket that actually blasted off.

Around the corner and along the Champs-Élysées, the design collective Vetements showed their SS20 collection of twisted and tortured streetwear in a branch of McDonald’s, barely cleaned for the occasion. Most designer’s ambitions for the scale of their shows sit someplace between the two: it’s unlikely we’ll ever see a fashion house quite as indulgent of a designer as Chanel was of Lagerfeld during his 37-year tenure. Then again, Chanel only had 18 outlets for ready-to-wear in North America when Lagerfeld joined. In his final year of designing, the turnover was reported as £8.7bn. Who doesn’t deserve a bit of song and dance after that?

Abloh’s Vuitton was indicative of a general urge this season towards either flights of fantasy, or dystopia — heaven or hell. Obviously, the former is far more commercial, but personally I like fashion as a form of rumination about the state of the world. And it’s not looking so rosy. After Raf Simons’ powerful, personal, even painful statement, Rick Owens added his voice to the mix. He named his collection Tecuatl, his grandmother’s maiden name, and used it to explore his Mexican heritage in response to Trump. So the collection combined Aztec hieroglyphs and the United Farm Workers’ logo (Owens is donating the proceeds to them) and was shown on a slippery slab of raw clay from the Los Angeles studio of artist Thomas Houseago.

The progression of Owens’ clothes themselves, to the insistent beat of drums and chanted music, resembled a pageant from another universe; the garments, the costumes of a glam-rock Estonian Eurovision Song Contest entrant. Which I mean as a compliment — and is largely down to the perspex-soled hooker heels for him. The clothes above them, however, were, as always, some of the most interesting and progressive shown in Paris, lashed with laces, sequinned, pointed-shouldered, with sportswear oddly mixed in until the lines were blurred entirely between casual formal, up and down.

Owens’ approach to fashion is fascinating, and strange in that, for all its extremity — and those heels are extreme — it has an incredibly loyal customer-base and a sturdy commercial bedrock. His business turnover exceeds €100m annually. And yet Owens’ aesthetic is utterly uncompromising, as often is his message. Which generally is that life may not be a bed of roses, but you can make hay while playing in the mud.

Follow @FTStyle on Twitter and @financialtimesfashion on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments