Fears rise that US-China economic ‘decoupling’ is irreversible

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Last month, Robert Zoellick, former president of the World Bank and US trade representative, addressed a group of top US executives with business in China with a warning and a challenge. At Washington’s Ritz-Carlton hotel, with Cui Tiankai, China’s ambassador to the US, in the audience, Mr Zoellick asked if the gathering was “ready” for a slide into US-China conflict.

“The 20th century painted a shocking picture of industrial-age destruction; do not assume that the cyber era of the 21st century is immune to crack-ups or catastrophes of equal or even greater scale,” Mr Zoellick said. “You need to decide whether you think the United States can still co-operate with China to mutual benefit while managing differences, and if so, how.”

His words captured the fears — particularly within parts of Washington’s economic and foreign policy establishment — that US President Donald Trump’s trade war against Beijing has paved the way for an irreversible “decoupling” of the world’s two largest economies.

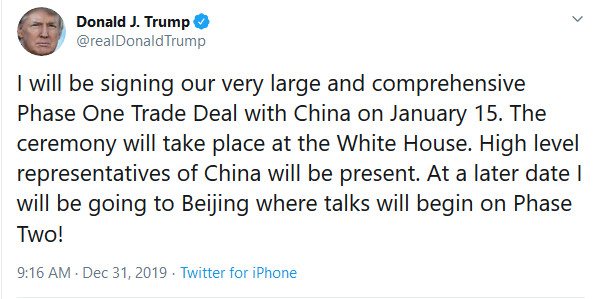

Later in December, Mr Trump and Xi Jinping, China’s president, agreed a truce and “phase one” deal that paused commercial hostilities and even rolled back some recent tariffs imposed by Washington on $360bn of Chinese imports. But many experts involved in US-China relations say the unravelling of more than two decades of increased economic integration between the two powers is likely to continue.

Many US companies are shifting supply chains, both in terms of production and sourcing, to other Asian countries, in an effort to avoid the hit from existing levies and the threat of new ones.

The drive towards a growing separation between the economic universes of Washington and Beijing, creating two distinct spheres of influence in the world economy, extends beyond traditional goods and services. It is most acute in advanced technologies, as the US aims to shield innovations in artificial intelligence, robotics and genomics from Chinese hands. Some US universities are nervous about hiring and keeping Chinese researchers, for fear they could be targeted by US authorities as agents of Beijing espionage.

The Trump administration has slapped on export controls that prevent US sales to companies including Huawei, the Chinese telecommunications equipment manufacturer, on national security grounds. This month, Washington proposed banning foreign sales of satellite imagery software without a licence — the first in a series of goods targeted for commercial restrictions based on a 2018 law enacted by Mr Trump.

Close observers of the US-China tech relationship warn that Beijing will attempt to respond in its own way. “Faced with US export bans on key technological inputs, Beijing’s goal is now no less than to create national champions in every segment of its tech supply chains — from electronics assembly, to chipmaking and to chip design as well,” says Paul Triolo, head of geotechnology at the Eurasia Group in Washington.

“We are already in the age of the splinternet. I expect to see decoupling in telecom, internet and ICT services, and 5G systems. We will all be worse off, however, if blanket bans and barriers supplant risk assessments,” Mr Zoellick has said. “The best US response to China’s innovation agenda is to strengthen our own capabilities and to draw the world’s talent, ideas, entrepreneurs and venture capital to our shores. We will succeed by facing up to our own flaws, not by blaming others,” he added.

In mid-2019, as trade tensions between the US and China reached a high pitch, worries grew that the decoupling would extend to capital markets. This, as the Trump administration floated proposals to limit Chinese listing on US stock markets and limit US investment in Chinese companies.

Those ideas, as well as notions that Beijing could decide to sell off its massive holdings of US Treasury debt, never appeared to move past the embryonic stage. This suggested that there are still limits to the evolving separation.

Senior Trump administration trade officials have not embraced the term “decoupling” and deny that they are trying to wrench the economies of the US and China apart, even if the most hawkish members of Mr Trump’s team believe this could be healthy. Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative, said the “phase one” deal agreed with China was “a first step in trying to integrate two very different systems to the benefit of both of us”.

Kevin Rudd, the former Australian prime minister, and president of the Asia Society Policy Institute, has said the “present and prospective economic relationship is much more interconnected than the increasingly wild use of the term decoupling might suggest”. In a lecture in California in November, he also warned officials that “loose or inflammatory language” could become a “self-fulfilling prophecy”.

Mr Rudd added: “A fully decoupled world would be a deeply destabilising place.” It would undermine the “global economic growth assumptions of the last 40 years, heralding the return of an Iron Curtain between east and west and the beginning of a new conventional and nuclear arms race, with all its attendant strategic instability and risk”.

Comments