‘Draghi put’ holds Italy’s bond markets in thrall

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

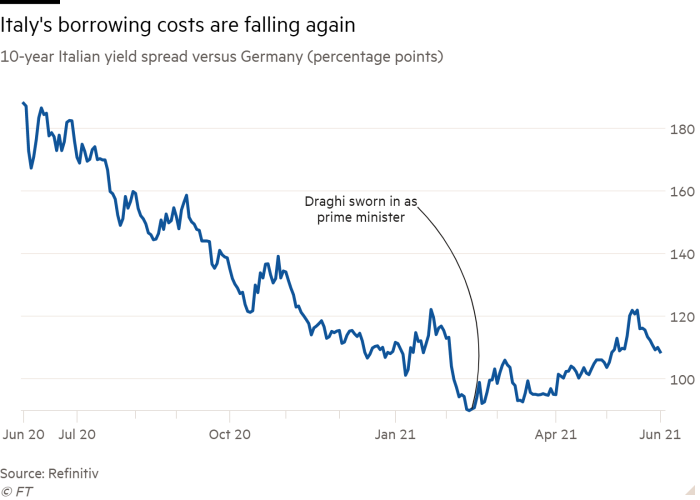

In his eight years as president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi developed an almost legendary ability to rein in borrowing costs for eurozone governments. Investors appear to be crediting him with similar powers as Italy’s prime minister, judging from the calm that has descended on the region’s bond markets since he took office in February.

Italian bond prices pushed higher, cramming down borrowing costs, when Draghi switched from former central banker widely credited with taming the eurozone debt crisis a decade ago into a politician. Following a brief wobble in recent weeks, as investors grew anxious that the ECB might soon begin to withdraw its emergency stimulus, Rome’s borrowing costs are back at their lowest in a month.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs have dubbed the former ECB chief’s power over bond markets the “Draghi put”. “The pricing of Italian sovereign risk points to confidence in Draghi’s ability to contain political risk,” the bank wrote in a note to clients last week.

Investors have signalled their support for the prime minister’s plans to overhaul Italy’s bureaucracy while spending €205bn of EU recovery money. The all-important spread that Italy pays on its debt relative to interest costs on ultra-safe German 10-year bonds stands at just above one percentage point, not far above February’s five-year trough.

“There’s definitely a view in the market that Draghi can do no wrong, that everything he touches turns to gold,” said James Athey, a bond portfolio manager at Aberdeen Standard Investments.

Some fund managers sense an opportunity to shake Italy out of decades of low-growth torpor. They are betting the stability provided by Draghi’s national unity coalition provides an ideal backdrop for the reform programme as Italy deploys one of the largest shares of the EU’s €750bn pandemic recovery fund. The government has established a watchdog to oversee disbursement of the cash, and introduced measures to streamline bureaucracy and speed up infrastructure development.

“This is exactly what Italy needs to tackle its longer-term issues. It is targeted fiscal spending aimed at the right reforms,” said Gareth Colesmith, head of global rates at Insight Investment. “That’s why we’re positive on Italy.”

The direction of Italian spreads has repercussions beyond its borders. As the eurozone’s largest government bond market — and one of its riskiest — Italy sets the tone for high risk assets across the bloc. For now, the “Draghi effect” has helped to paper over worries about Italy’s substantial public debt of over 160 per cent of GDP, according to Andrea Iannelli, investment director at Fidelity International.

That may be overly optimistic, Iannelli argues. Plans are one thing, but deploying billions in investment could reignite old political conflicts. There are some signs of discontent among voters, with the anti-EU Brothers of Italy — the only major party not to support Draghi’s coalition — currently in second place nationally after gaining steadily in the polls.

“It’s not going to be plain sailing,” Iannelli said. “And plain sailing is something the market has priced in.”

As a technocratic appointment, Draghi is not expected to continue as prime minister beyond the next election. The coalition’s term must end by 2023, although a vote could come as soon as next year if Draghi decides to run for Italy’s presidency.

Chiara Cremonesi, fixed-income strategist at UniCredit, said markets may soon begin to worry about what may follow the unity coalition. “Investors are positive on Draghi, so they are obviously concerned about how long his government is going to last,” she said. UniCredit isn’t expecting an election in 2022, but an “increase in political noise” could push spreads back up to the level of around 1.2 percentage points reached before Draghi arrived, she added.

Even without a political flare-up, the relative calm in markets depends on the ECB and its continued support for markets through the €1.85tn pandemic bond-buying programme introduced by Draghi’s successor at the central bank, Christine Lagarde. A eurozone bond sell-off in May, which widened Italian spreads while also lifting German yields, shows just how sensitive markets have become to any suggestion of an early “tapering” of net purchases from the current rate of €80bn per month.

Since then, a succession of ECB officials, including Lagarde, have reassured investors that it will maintain its efforts at this month’s policy meeting. Investors think the ECB will be very sensitive to any rise in Italian yields in particular. As long as the former ECB boss remains in office, some are betting the central bank will be more likely to keep the stimulus taps running.

“As long as they think Italy is doing sensible reforms they will keep providing support,” said Colesmith.

Comments