Why the UK is an attractive destination for economically valuable migrants

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

UK migration policies have rarely won much praise in recent times. The dramatic arrivals of migrants in small boats have generated plenty of headlines but little support for the government, with critics on both sides of the migration argument launching attacks.

Meanwhile, Brexit opponents complain how restrictions on movement to and from the EU have burdened people and businesses — and even Brexit supporters struggle to identify the benefits of the new controls.

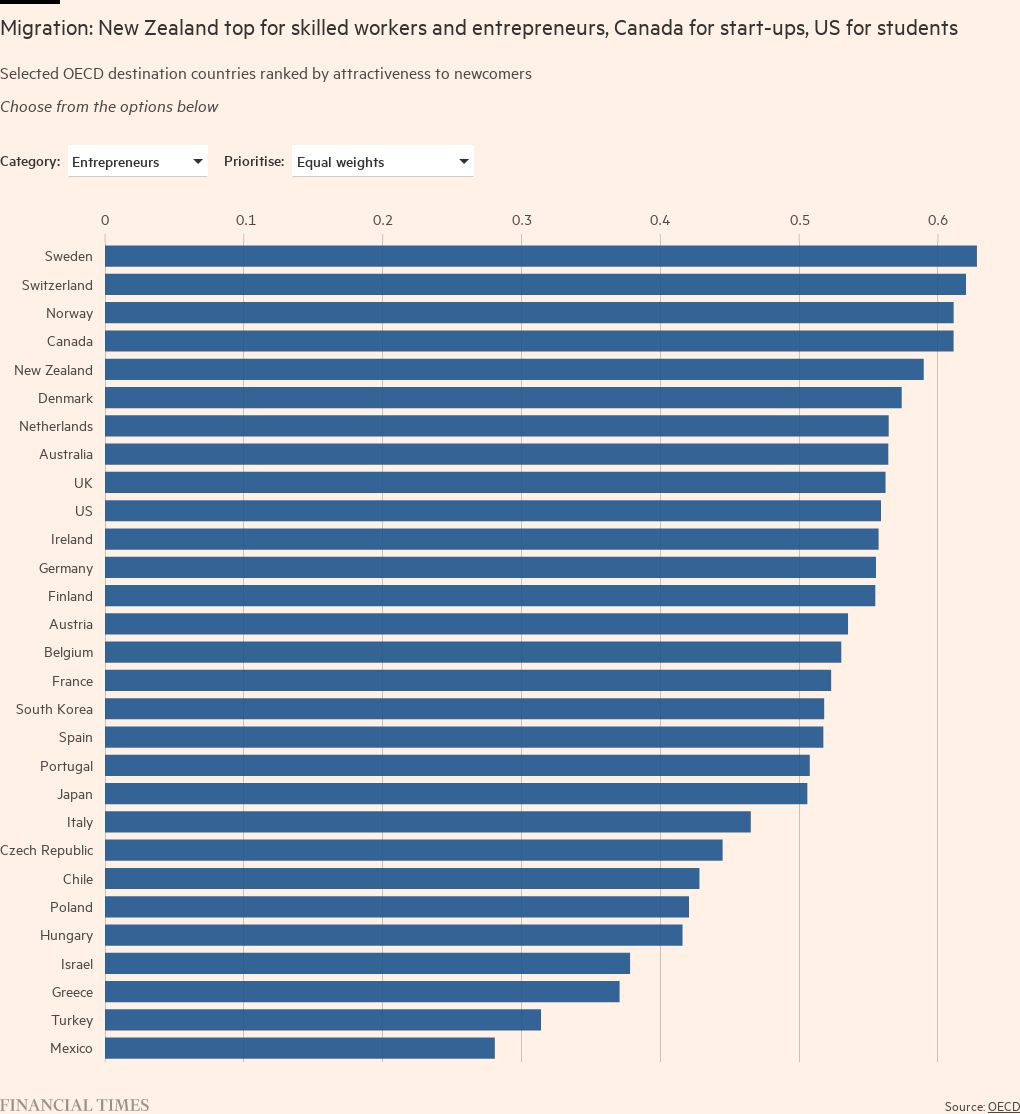

So it comes as something of a surprise to find the OECD, the developed countries’ club, lauding the UK over immigration policy — specifically the approach to highly skilled workers. It writes in a regular migration policy review of its 38 member states, published this year, that Britain has seen “the largest improvement in the ranking” since the last report in 2019. That’s due, it says, mainly to abolishing quotas for highly skilled workers and for migrants’ success in getting jobs in the UK. That puts Britain in the top 10, a pack led by New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland and Australia.

However, the value of the OECD’s survey lies not in the ammunition supplied for political battles but in the focus it brings to particular types of economically valuable migrants: entrepreneurs, start-up founders and students as well as highly skilled workers. The report ranks countries by what it calls “attractiveness to newcomers”, looking at different dimensions ranging from quality of life and work opportunities to tax and spousal immigration rules, mostly represented via measurable data sets, such as migrant unemployment rates or visa refusal percentages.

There is as much art as science in putting together these rankings, but the results bear food for thought. In broad terms, there are few shocks. The Nordic countries do well, as do Australia, New Zealand and Canada. The US is less good for skilled workers than might be expected given its economic potential because it has tough visa rules. But it is top for university students and second (behind Canada) for start-ups.

Low tax rates, which many well-paid workers and entrepreneurs might find appealing, do not alone result in high rankings in the OECD table if other factors such as education standards and infrastructure are poor.

Health quality matters, too, in the OECD’s view. The Nordic countries, Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands all do well on this score. Estonia, Hungary, Latvia and Portugal are otherwise attractive countries for workers, students and entrepreneurs alike, but are held back by their low health scores. So, notably, is the US.

It is striking how the countries that appeal to migrants entering via official routes as highly skilled workers, students and entrepreneurs are also those that draw large numbers of undocumented migrants, including refugees from war and oppression.

As the OECD argues, migration policies are choices. Japan and South Korea are economically successful states offering a good quality of life. Yet both have opted for restrictive immigration strategies that not only limit access to foreigners, they also hold back domestic development by controlling labour supply. Other countries low down the migration tables have a host of problems to tackle beyond immigration policies per se: Turkey, for example, and Mexico.

The world doesn’t stand still, though. Countries are in competition with each other for skilled workers, students and entrepreneurs. Over time, some of today’s leaders will lose ground and laggards catch up, as the former Communist states of eastern Europe have done.

For potential migrants, the best approach is to keep an eye on changes in everything from the political environment to details of migration law. And spread your bets, if you can, by living, studying and working in different countries so that you’re well placed to move again, if you have to or want to.

Stefan Wagstyl is the editor of FT Wealth and FT Money. Follow Stefan on Twitter @stefanwagstyl

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments