Rising interest rates cool sizzling rally in emerging markets

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The rush into emerging market assets since the depths of the coronavirus crisis a year ago is facing its first serious test as rising US interest rates revive memories of the “taper tantrum” of 2013.

Emerging market stocks sailed almost 90 per cent higher in US dollar terms from the nadir in March to a historic peak last week, according to MSCI’s broad index of equities in 27 countries. The surge stemmed in part from a ferocious hunt for returns after central bank stimulus depressed interest rates in developed markets to record lows.

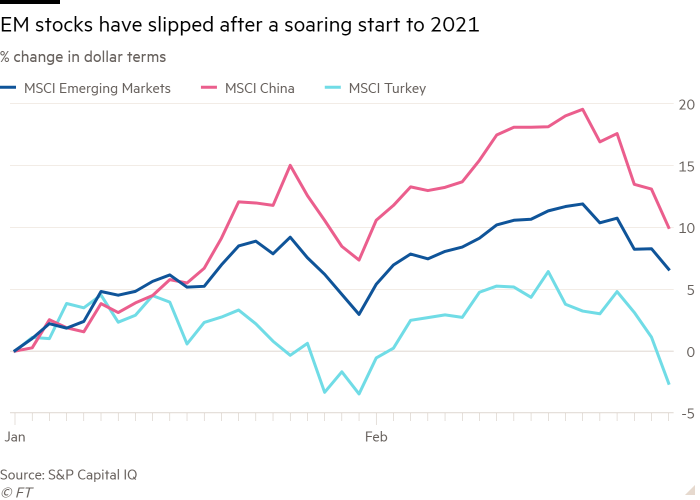

But a sharp drop in developed-market government bond prices since the start of 2021 has sent borrowing costs sharply higher, and started to ripple into emerging markets. MSCI’s EM stock barometer has slipped about 5 per cent from last week’s high, reflecting drops in countries stretching from China to Turkey and Brazil.

“There’s no doubt that yield curve steepening worldwide is starting to spill over into other asset markets and the last thing we need right now is a full-blown bond and equity market sell-off,” said Win Thin, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman.

To some analysts, the set-up this time around is similar to 2013, when investors fled EM assets as the US Federal Reserve signalled an end to the ultra-loose monetary policies that had given them such a boost.

Thin at BBH notes that the Fed will probably seek this time to reassure markets it will only slowly withdraw the extraordinary stimulus measures it deployed during the depths of the Covid-19 crisis.

Nevertheless, some sectors are feeling the pressure. Chinese markets, which have been among the best performers due to the country’s rapid recovery from coronavirus, have dropped over the past week.

The CSI 300 index of Chinese equities has fallen about 6 per cent on a dollar basis from its February high, while Shenzhen’s technology-focused ChiNext market is down 13 per cent. Turkey, another large EM, has endured a roughly 8 per cent decline since February 15, according to an MSCI index.

Meanwhile, Brazilian markets have faced serious ructions after Jair Bolsonaro, the populist rightwing president, fired the boss of state oil company Petrobras for failing to keep pump prices low.

Still, some analysts and investors argue that expectations for a brighter economic outlook in many countries will help dull the risk posed by rising global interest rates.

With vaccines coming into sight, says Tom Clarke, partner and portfolio manager at William Blair Investment Management, “you can argue about how many quarters there will be of lost or much reduced income but it’s the kind of thing you can look through, even if it’s a long way into the future. That has caused a sea change in EM equities and currencies.”

This, he says, is part of a more fundamental change. Before the pandemic, several factors were weighing against emerging markets: protectionism in the US and elsewhere, rising tensions between the US and China, the uncertainty over Brexit — all of which have been resolved, to a greater or lesser extent.

“There have been worries about a hard landing in China for several years and, lo and behold, it delivered positive growth, last year of all years,” Clarke said.

Not all EMs will come out of the pandemic in equally good shape, however. One factor crucial to their prospects will be their ability to deliver productive investment.

As recent FT analysis shows, foreign direct investment slumped around the world last year but held up remarkably well across Asia. In China and India, it grew in 2020 by 4 per cent and 13 per cent, respectively. In contrast, Africa and Latin America registered the largest contractions of any regions for many components of FDI including mergers and acquisitions, project finance and greenfield investment — the kind that generates new jobs.

Investors have also welcomed domestic spending. Part of India’s response to the pandemic has been to increase public spending on infrastructure by 50 per cent over its 10-year average. Brazil, where such investment has been squeezed for decades, has concentrated its pandemic response on subsidies for consumption — popular in political terms but less good for building growth.

Paul Korngiebel, emerging markets portfolio manager at Boston Partners, describes coronavirus as “the massively distorting event that creates winners and losers by [country and] industry sector as policy differs in response to Covid”.

Just as in advanced economies, the focus of many EM investors has been on tech. Over the past 12 months, shares in electric vehicle maker Tesla are up 350 per cent in New York. Shares in Nio, its Chinese rival, also listed in New York, are up more than 1,000 per cent.

Korngiebel worries that, in some sectors, investors may have brought too much future growth into the present and that some valuations are getting stretched. Conversely, he sees opportunities in sectors, such as regional airlines, that have been crushed, as investors have perhaps prematurely written them off.

“We are really dealing with the aftershock of Covid right now,” he says. “It’s not over from an investor point of view — the pig in the python is only half digested.”

Comments