UK watchmakers battle for international credibility

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Disorganised, parochial and often more secretive than a cold war spy network, the UK watch industry has been lost in the shadow of its Swiss counterpart for decades. Some have even suggested there is no such thing as British watchmaking.

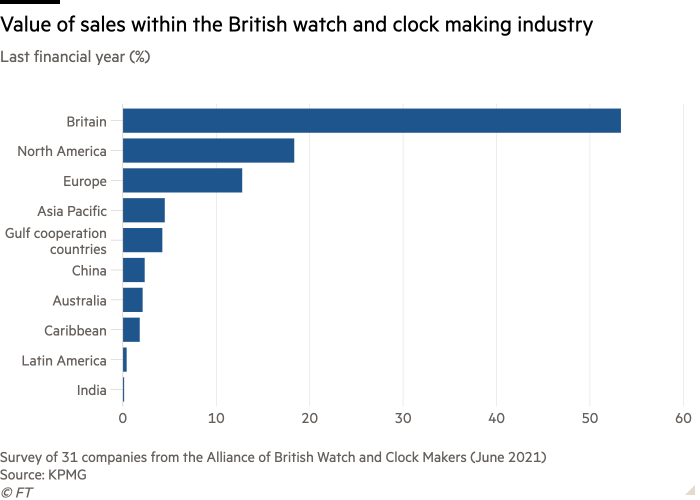

But a new bellwether report on the UK’s watch and clockmaking industry, published on Friday by consultants KPMG, indicates there are as many as 100 domestic companies in the sector, selling some 1m timepieces a year with combined revenues of about £100m. The report also suggests that, in spite of Brexit and the pandemic, brands are confident these figures will rise.

The report was commissioned by the Alliance of British Watch and Clock Makers, a trade body founded last year by venerated watchmaker Roger Smith and Mike France, co-founder of the world’s first online-only watch brand, Christopher Ward. The alliance now has more than 60 members, 31 of whom responded to KPMG’s survey.

“If you’re trying to get somewhere, best you know where you are now,” says France. “At the current rate of growth, in 10 to 15 years’ time, we could grow this industry to a value of circa £1bn.”

Smith, the alliance’s chair, says the report gives cause for optimism. “There is no reason why the British watch industry cannot be scaled up, if that’s what we wish,” he argues, adding that the alliance has identified 20 start-up watch companies preparing to launch. “Our ambition is to prove to Britain and the world that our aspirations are bigger. [British brands] Bremont and Christopher Ward have shown that it can be done.”

Bremont, which reported turnover of £19.1m in the 12 months to June 2019 in its last full set of accounts, has not joined the alliance and did not take part in the survey. Giles English, one of the two brothers who founded the company in 2002, says: “There is a new British watch company opening up every week, which is great. But if you’re getting your watches sourced offshore, that’s not British watchmaking.”

In March, Bremont opened a 35,000 sq ft manufacturing and technology facility in Henley-on-Thames (pictured top), reported to have cost more than £20m. It has said this will enable it to produce 50,000 watches a year on British soil, roughly five times its current output.

Christopher Ward’s watches are assembled in Switzerland and the company has no UK manufacturing facility. Its sales were about £15m in 2020, according to France — an increase of 30 per cent, year on year.

However, English says the financial burden of investing in UK manufacturing has to be shared. “I want to see a number of those brands, like Christopher Ward, manufacturing in the UK and investing in British watchmaking,” he says. “They’re big enough. So make that investment and stop making it abroad. That would change our view on this [the alliance]. Otherwise, it’s just chat.

“We have amazing craftsmanship in the UK. It’s an immense skill, but it’s different to producing watches at volume and creating an industry. We can’t be the only one investing.”

Smith, who hand-crafts about 10 high-end watches a year in his Isle of Man workshop, agrees that “manufacturing in Britain is virtually non-existent”. He adds: “There are engineering companies doing things in Britain, but they’re focusing on simpler components: cases and dials, for example. Where we’re lacking is the real technical component-making.”

Of the 1m pieces produced by, or at least for, British brands, it is thought the vast majority are low-cost quartz watches outsourced by fashion brands such as Sekonda and Accurist. Kristan King, the KPMG partner who oversaw the report, says the reality of manufacturing in the UK is akin to a chicken and egg problem. “Respondents indicated a strong willingness to procure inputs from within Britain but felt suitable British suppliers, appropriately balancing quality and price, are generally not currently available,” he says.

English doubts it will ever be possible to create an ecosystem in which these low-end brands source parts in the UK. “The problem is, those companies are making watches you would never be able to manufacture in the UK cheaply enough and keep to that price point.”

France wants to see the UK become an innovation hub for the watch industry. “We are entrepreneurial, more so than the Swiss,” he says. “Just as Formula One has established its base in Northamptonshire, so I think the UK industry can establish itself as a place of innovation in watchmaking.”

Trade Secrets

The FT has revamped Trade Secrets, its must-read daily briefing on the changing face of international trade and globalisation.

Sign up here to understand which countries, companies and technologies are shaping the new global economy.

He also believes Brexit and a move to localisation following the pandemic will oblige UK companies to look to manufacture closer to home. “The trend is towards a greater level of insourcing than outsourcing,” he says. “Increasing pressures mean that’s going to be prevalent for some time.”

But English, whose company employs 130 people, including about 50 watchmaking technicians, is not convinced. “You have to have more watch companies wanting to manufacture in the UK, because it’s a volume game,” he says. “Some have that ambition, but the bulk of them don’t. If there was another watch company that set up a dial-printing business and was very good at it, we would love that because we would get our dials from them.”

What the UK lacks in manufacturing power, though, it makes up for in creativity. The KPMG report concluded that 97 per cent of British watch and clockmakers design their pieces in the UK. Britishness has a value, says Smith, even if it cannot be easily defined. Citing several UK watch companies, he says: “If you take anOrdain, with their enamel dials, they’re doing something very unique. And the characters behind, say, Fears or Mr Jones, give them something different that you don’t see in Switzerland.”

English agrees that there is value in Britishness and British watchmaking heritage but says that major watch export markets have a very narrow understanding of it. According to KPMG, only 45 per cent of UK watches and clocks are exported. “We’re doing a lot of research in China into how they view Britain and they don’t see us being a nation of engineering,” he says. “They see us as being a nation of craft. And that is a challenge.” Bremont is due to open a boutique in Shanghai this year.

One benefit of having an industry body, says France, is that UK watch companies are represented at government level. “We now attend monthly government business department meetings about what’s happening in the economy,” he says. “The government is very interested in British watch and clockmaking becoming part of the push to represent the best of British overseas.”

In compiling KPMG’s report, King says he saw signs of an industry galvanised. “It was apparent that the interviewees were very enthusiastic about . . . the potential to improve or expand [the sector] through knowledge-sharing and initiatives that may be driven by the alliance,” he says.

Smith says: “There’s been denial that there is a watchmaking industry out there. The success of the alliance . . . has been to showcase that there is.”

Comments