I covered the City for 20 years — here’s what I learnt

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The first words to appear under my byline at the FT were about two children’s television programmes. Butt-Ugly Martians and Pinky & Perky, I wrote in January 2001, would launch on ITV using “computer-generated images” and — sharp intake of breath — with their own websites.

Shortly afterwards I recorded another revolutionary development: an “in-car informatics” system that would give Ford drivers traffic information to plan routes. The following month I reported on a survey showing that half of FTSE 100 companies used “webcasting” to share information with investors.

Clearing my desk after nearly two decades at the FT, I have found myself leafing through the old red cuttings books into which I once painstakingly glued each day’s articles. It is not just the technologies that date the writing. Short as they are, the 150-word pieces that constitute the bulk of my output during those early weeks mainly consist of a mind-numbing succession of numbers — dividends, earnings per share, pre-tax profits — which leads me to question whether even the most dedicated readers could have made it to their end.

Some things don’t change. Writing about commerce in an engaging way is still a challenge. Readers, even FT readers, are still in need of diversion now and then, just as they always were. My most read piece in my last years of journalism at the FT was not a critical look at the Agnelli empire or an in-depth analysis of France’s Saint-Gobain. Instead, it was my account of changing the colour of my hair from brown to its natural white.

But one thing that has changed in my 25 years of working in and then writing about finance is my understanding of business — and my understanding of how it should fit into society.

By late 2008, I had graduated from Pinky & Perky to a new job as companies editor, running the news desk responsible for corporate coverage. Two weeks in, I flew out to visit our New York bureau. When I boarded the plane, on the morning of September 15 2008, Lehman Brothers and insurance giant AIG were still doing business. By the time I had landed, Lehman had gone under and AIG was in special measures.

The atmosphere on Wall Street was electric. My colleagues and I went for a drink in the evening beside the Lehman building, which had a ticker tape screen running around it that — in normal times — displayed stock prices. That night, I remember the screen being filled with fire.

If intended, the visual commentary certainly hit the mark. It was not just the financial system that looked set to go up in flames — but also many of our prevailing assumptions as FT journalists.

At the FT as elsewhere, we had missed most warning signs. Looking back on what I wrote for the FT’s Lex column in the run-up to the crisis I am struck by my — and colleagues’ — relative complacency. I warmly praised the decision by Spain’s construction companies to diversify overseas (a leading cause of their downfall), and forecast an “undramatic” divergence in European sovereign debt spreads. We thought we were sceptical observers, pointing out dangers that others were not clever enough to spot. Maybe not . . .

This was a salutary moment for me, because it reinforced a lesson I had been learning since working in the City of London and on Wall Street in the 1990s: that the failures which led to the crisis were more of behaviour and character than of financial instruments or processes. The tales of casual greed and of ordinary people misled and deceived by irresponsible bankers are familiar. But there was one element to the crisis that I have seen repeated in many different forms: overweening power. In the business world this breeds all sorts of crises, from the personal to the systemic.

Martin Sorrell’s 33 years at the advertising company he built, WPP, ended in controversy in part because he seemed to treat the people who worked most closely with him, such as his driver, with contempt. One reason Lehman went under was because it was run by a joint chairman and chief executive who, by 2008, had accrued almost total dominion, and who was not held to account by those with a duty to do so. Dick Fuld’s board members neither delved deeply enough into the real activities of the bank, nor did they challenge the person running it sufficiently. Being on the Lehman board, it seemed, was a social honour rather than a fiduciary responsibility.

Chief executives like these do not appreciate having their judgment questioned, particularly by reporters. The price of doing so, I have often found, is to be summoned to “punishment” lunches at smart restaurants. I had an agonising two hours at Le Pont de la Tour next to Tower Bridge in 2012, interspersing delicious food with gritted-teeth exchanges with Ivan Glasenberg, chief executive of the commodity giant Glencore, who was outraged I had questioned the logic of its proposed takeover of Xstrata.

Business bosses who enjoy too long a tenure lose self-awareness. They become reluctant to promote people around them who will challenge their point of view. Meanwhile, questioning a boss who enjoys such stature becomes all but impossible, encouraging hubris, and leading to bad business decisions.

Depressingly, efforts to address this and, in general, improve corporate governance in the US and elsewhere since the financial crisis have been lukewarm. Boards continue to fail in their duties. Look at Kids Company. This worthy British charity, with its establishment cast of supporters including prime minister David Cameron, collapsed in 2015. Its trustees included Alan Yentob, the former boss of the BBC, who, along with his co-trustees, appeared too in thrall to its charismatic founder, Camila Batmanghelidjh, to question its financial health.

Of course, there are issues beyond weak boards and omnipotent chief executives. Company bosses feel short-changed by the press, which they believe fails to give them a fair hearing. But one scandal after another has further eroded the public’s trust in business.

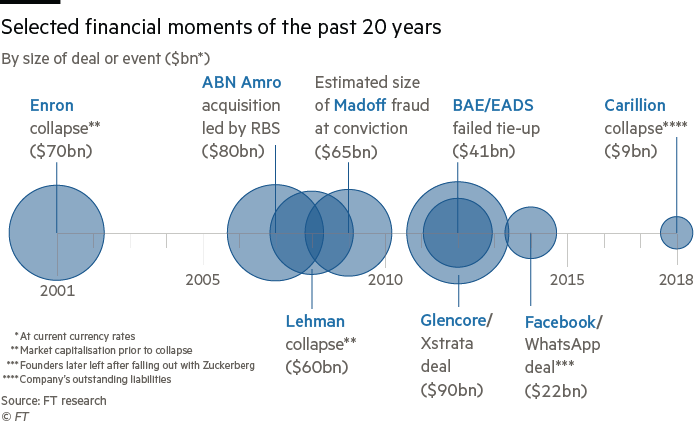

My career at the FT began at the time of the collapse of Enron, whose fraudulent managers brought down not just the US energy company but with it the auditors Arthur Andersen. Every year since has witnessed a repeat. Bernard Madoff and his Ponzi scheme; Italy’s Parmalat and the €14bn hole in its accounts; the aggressive selling of payment protection insurance in the UK. Even more shocking, perhaps, are the company bosses who choose to exploit their investors and staff while staying within the law. Philip Green walked away from BHS in the full knowledge its pensioners would likely be impoverished; the owners of Carillion paid themselves large dividends well aware that small suppliers would go bankrupt if the contractor failed.

I last interviewed Green in 2004, when he was in the midst of his second attempt to take over Marks and Spencer. With hindsight, that meeting gave a clue to the revelations about his behaviour that have surfaced since. He was at the height of his success, with Topshop the grooviest name on the British high street; the rest of his Arcadia empire churning out profits; and his lavish parties the talk of the press. But his inability to acquire the British retailer made him an angry man — one prepared to take out his frustrations on a reporter. I had to leave the meeting earlier than planned, pursued by shouting and swearing.

Deals seem to encourage the worst excesses. They can be unrealistic, like the failed €36bn tie-up between the European defence giants BAE Systems and EADS in 2012; overpriced and overleveraged, like the takeover of the UK’s airports by Spain’s Ferrovial in 2006; derailed by personal acrimony, like the $22bn Facebook-WhatsApp deal that closed in 2014; or dangerously hubristic, like the €71bn acquisition of ABN Amro by RBS and two other European banks in 2007.

What unites them is that each deal was trumpeted by its proponents as value for money, as revenue-enhancing, as strategically logical. When I covered the airports deal for the FT’s Lex column, BAA used to summon me to its offices in Victoria, where staff would attempt to blind me with science, showing one chart after another that proved how good a price they were getting for the company. Calculating a deal premium has always been a dark art, one that has generated many millions in advisory fees. Showing, sometimes, how far chief executives’ promises are from the truth is one of the most important jobs we do at the FT.

As a child, lucky enough to grow up in comfortable circumstances in London, I simply assumed that the world was run efficiently by the grown-ups. It has been a slow — and sometimes painful — dawning that in fact most companies are run pretty badly.

The second lesson I learnt from the financial crisis, and the years since, is that ignorance of financial affairs is widespread — and dangerous. Yes, the banks were responsible for egregious behaviour. Yes, policymakers from central bankers to regulators to finance ministers failed to address distortions in the market that, in retrospect, look glaringly obvious. But the “ordinary” people who feel so robbed by those in charge also bear a responsibility.

If you took out a mortgage on a house with practically no equity, you took a risk. If you borrowed several times your monthly income on credit cards, you took a risk. If you deposited your savings with a little-known Icelandic bank offering incredible rates, you took a risk.

Such decisions also played a role in the financial crisis. And they were also irresponsible. But in part they were driven by most people’s lack of understanding of financial realities and basic economics. Such ignorance — in modern societies — is inexcusable.

Business journalists such as myself are not exempt. I remember sitting in a very grand boardroom on the top floor of Lehman’s very grand building in Canary Wharf in 2005, with my colleague Gillian Tett, who was handing over to me on Lex before becoming markets editor. Unlike Gillian, I allowed a slew of new vocabulary — slicing and dicing loans, mezzanine financing, subordinated debt, collateralised debt obligations — to wash over me. The increasing complexity and specialisation of the language used to describe financial instruments was one reason most of the press failed to spot the crisis around the corner. But it is not an excuse.

Early in my career I spent several years in our personal finance team. One of our regular articles encouraged readers to write in with financial dilemmas, which I asked experts to answer in print. FT readers are a sophisticated lot but, from their questions, it was clear why financial advisers are so often able to exploit the public. If you don’t know how insurance works, it is difficult to assess which premium to pay. If you don’t understand interest rates, you can’t choose the right mortgage.

For rich societies such as ours, these qualify as basic life skills. They should be taught in primary schools. Without understanding how finance works, you cannot make the best decisions for your and your family’s lives. Without understanding how economies work, voters make political choices based on inadequate knowledge.

A widespread lack of understanding of basic economics has overshadowed reporting on Brexit over the past three years. It partly explains why, before the referendum, much of the public failed to see through the tall tales of the Leave campaign, and it partly explains why the Remain campaign resorted to simplistic forecasts of economic doom, which many rightly found preposterous.

It also explains why so few politicians appear to understand the risks to business, and thus to the economy, of our current political woes. It is extremely rare to find a politician who understands the commercial realities of managing a company or — God forbid — has actually run a business in the past.

In the UK at least, there is often a contempt for commercial activity, for making money, which precludes such understanding. The schools that — too commonly — are the training ground for the metropolitan urban elite still inculcate little respect for the dirty business of doing business.

We all — teachers, journalists, politicians, chief executives — need to do a better job of explaining why business matters, how it is the taxes companies pay that fund our public services, why bank lending is necessary to fuel growth, and why prosperous employers mean prospering employees.

Leaders who look beyond the bottom line

Sir Charlie Mayfield

Chairman of John Lewis

Carolyn Fairbairn

Director-general of the CBI

Larry Fink

CEO of BlackRock

Business leaders themselves do a poor job of making their case in public. Brexit is only one example of the hugely important issues on which too many choose to hide in the shadows rather than speaking out.

There are exceptions. Sir Charlie Mayfield at John Lewis, Jürgen Maier, who runs Siemens UK, Paul Polman at Unilever, Carolyn Fairbairn, director-general of the CBI, even Larry Fink at BlackRock are among those who have fought to redress the balance, to show what links business to society and to broader purposes than the profit motive. But they need others to help change perceptions.

Many businesses are badly run, but business is not bad. Most people running companies whom I have met over the past 18 years care about the people they employ. Most entrepreneurs believe that there is a purpose to running their company which is greater than just making money.

The voices of big business, and the big business baddies, too often drown out the stories from the millions of small companies that make up the bulk of employers in the UK and across the globe. I’ve interviewed many of them in the past few years, in Scotland, outside Cambridge, in Bilbao and Munich. Many are family-run, on the second or third generation, focused on building sustainable businesses. Unlike the UK’s big supermarkets, gouging dairy farmers with ever lower milk prices, they have long and mutually dependent relationships with their suppliers. They look after their staff, turning apprentices into engineers and keeping people on their books during extended periods of illness.

The popular caricature of business, filled with profiteering bankers and gig economy exploiters, simply does not reflect the reality. But it is up to business to dispel it.

Perhaps Michael O’Leary would no longer call me “love” and put his hand on my knee as he did when I interviewed him in 2005, while he defended Ryanair’s decision to add “frills” like snacks to its ticket prices. But business needs to do more than change its culture. It must challenge itself on what its purpose really is, not just what its investors want. It must be prepared to tackle the great ills of our time, such as climate change or modern slavery. And it must be louder in explaining why it matters.

In 2016 I interviewed Gloria Steinem, the great American feminist. She argues that women are the only group of people who become more radical with age. As I approach 30 years in the world of work, I feel more and more strongly that business must embrace a new direction — one in which I hope to play an active part. I intend to do less preaching, and more practising. If I can help any business change in the way I believe it should, I also hope we will continue to be held to account, responsibly — and readably, please — by my colleagues at the FT.

Sarah Gordon is the FT’s outgoing business editor

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Letters in response to this article:

So few lessons learnt / From HJ Ruff, Bournemouth, UK

Let’s not leave out Gina Miller’s name / From C G Pradeep Kumar Mumbai, India

Comments