Luxury goods lose gloss as consumer enthusiasm begins to wane

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Stellar growth appears to have gone out of fashion in the luxury goods industry. After a five-year run of soaring revenues and profits despite the financial crisis, a sales slowdown reflecting patchy Asian consumer enthusiasm, volatile exchange rates and geopolitical instability has taken its toll on some of the biggest names in this once unstoppable sector.

According to the BrandZ top 100 most valuable global brands ranking, compiled by Millward Brown, the value of luxury brands has slipped 6 per cent over the past year, outpaced by less glamorous sectors, including insurance, mass-market retail, telecoms and technology.

The category as a whole has been hit by anti-corruption laws in China that have weighed heavily on sales related to gift-giving. Student protests in Hong Kong, where 15 per cent of annual global luxury sales are made, have also taken their toll, as has Russia’s lurch into recession, triggered by the conflict in Ukraine.

But the leading factor in the fading fortunes of some of the industry’s most high-profile names has proven to be currency headwinds. Following the high-profile departure of both its chief executive and creative director announced in December, Gucci reported an 8 per cent first quarter sales fall last month, and signalled it would rebalance some prices as a weakening euro widens the differential between regions.

The onset of “logo fatigue” and a low euro have weighed heavily on revenues at the Italian fashion and accessories house, which slipped 16 places to 76.

Last month, Richemont, the world’s second-largest luxury goods company by market capitalisation, issued an unexpected profit warning, which analysts said was in part linked to the Swiss franc’s sharp rise in January, after the Swiss National Bank abandoned the cap on the franc’s value against the euro.

Exchange rate movements have led to significant regional price differences at many labels beyond Gucci, with the same luxury item now sometimes costing more than 50 per cent less in European capitals than in major Chinese cities.

Chanel, for instance, cut prices on its iconic handbags by more than 20 per cent in China and raised them by the same margin in the eurozone in March. By contrast Hermès said it had no plans to harmonise prices during its latest quarterly results in March.

“We have a very strong French and European customer base,” chief executive Axel Dumas told analysts.

“If we significantly increased our prices at this juncture, that would mean giving up on local customers and that is something we do not want to do.”

Hermès, which makes high-end leather goods such as the Birkin bag, has withstood the slowdown in the luxury market better than its competitors, and has said it expects sales this year to grow 8 per cent in constant-currency terms.

Yet, according to Millward Brown, it has lost 13 per cent of its brand value in the past 12 months. The research company has mooted that this may be due to the fact that, in the digital era, as communication becomes more instant and mobility more widespread, luxury brands must work harder to find the balance between ubiquity and exclusivity in the mind of the consumer.

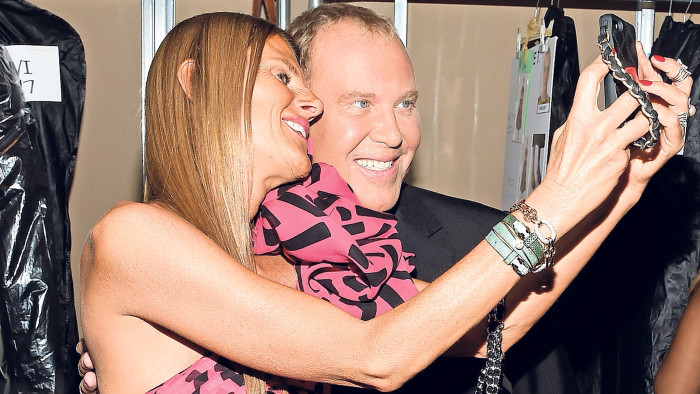

The conservative Hermès is hardly renowned for its online prowess, unlike accessible US luxury brands such as Tory Burch and Michael Kors. The latter has a fan base of millions on social media platforms such as Instagram and has ramped up ecommerce and mobile-commerce offerings, offsetting concerns over its aggressive retail expansion strategy and its subsequent risk of overexposure.

As Exane BNP Paribas analyst Luca Solca notes, many luxury megabrands, including Louis Vuitton, Gucci and Prada, have all now said they have the right number of stores, in part to protect the value of their brand across languages and geographies, especially in China which continues to be a powerful force for sales growth. Many of these labels have endured what Mr Solca describes as a “locust field effect”: the tendency of Chinese buyers to devour a new brand disproportionately, before quickly seeking another.

Comments