Cindy Chao’s east-west jewellery fusions augurs well for collectors

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Jewellery designer Cindy Chao’s eponymous business may be turning 15 this year, but a celebrity-studded bash to mark the occasion was always unlikely, regardless of the pandemic.

Ms Chao’s designs may be glamorous and statement-making, with gobstopper-sized stones surrounded by thousands more in pavé settings, set in impressive, sculptural forms, but her clients are notably private and discreet. From Thai royals to Russian and Asian tycoons, these collectors seek out Ms Chao’s so-called art jewels for something unique: wearable sculptures that sit between the rarefied worlds of high jewellery and fine art.

Ms Chao’s designs are influenced by her upbringing as the descendant of a Taiwanese sculptor and architect, but are crafted in Geneva and Paris. That east-west fusion has attracted a discerning clientele, for pieces that start at $100,000 (or $1m for her high-end Black Label collection). According to the company, turnover has increased 500 per cent since the business’s 2004 launch in Taipei, with profits up 150 per cent in the past five years.

Nevertheless, Ms Chao still refers to her brand as a “start-up”, especially compared with the large, storied houses, but she does admit the international interest has been a surprise. “I didn’t think that in 15 years’ time our reach would be so wide,” she says. “I would have never dreamt that sheikhs from the Middle East would fly to Hong Kong for 36 hours on a private jet with bodyguards, just for a chance to view my masterpieces.”

Today, international clients represent 40 per cent of her collectors, with the remainder coming from Asia. But that mix could soon change. The pandemic forced her to scrap plans for a London showroom this year and focus instead on Shanghai, adding to two others in Taipei and Hong Kong. “I think we’re making the right decision by going back to China,” she says.

This regrouping reflects a broader trend. Lockdowns around the world have kept Asian consumers at home, hitting luxury houses particularly hard. Luxury spending is heavily linked to tourism, which represents 40-45 per cent of sales of hard luxury (watches and jewellery), compared with 30-35 per cent for soft luxury (fashion and leather goods), according to Citi analyst Thomas Chauvet. Globally, flights were down 53 per cent year-on-year in July and August combined.

The large jewellery houses responded by announcing they would tour their high-jewellery collections around Asia, banking on China’s buoyancy. Consultants Bain & Co, which estimates the luxury industry will contract by 20-35 per cent this year, forecasts Chinese consumers will drive a global recovery, making nearly half of all purchases by 2025. Mainland China, says Bain, will account for 28 per cent of the market in 2020, up from 11 per cent last year.

Ms Chao is well acquainted with the growing sophistication and changing tastes of Chinese high-jewellery collectors. Today, she says, they know precisely want they want, noting that while her prime collectors outside Asia are aged between 40 and 55, those from China are in the 30-40 age group. “They’re able to spend the same amount of money as those in my other regions,” says Ms Chao. Moreover, this younger generation of wealthy Chinese are increasingly looking for something different. “This is not to say they’re tired of the big houses, but they will want something unique where you [the buyer] need to make an effort to find,” says Ms Chao.

Such a mentality bodes well for small, independent houses. Ms Chao’s pieces can take years to complete and attract waiting lists — new orders for her signature bespoke butterfly brooches are on hold until 2025 — prompting her to be increasingly selective with clients.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has brought out customers’ shrewder side. “They’re not just looking at my pieces as luxury accessories but as an investment,” says Ms Chao. “People with cash in hand are very conscious about what’s coming. Jewellery is a much more portable asset and [clients want to] invest in something solid but portable.”

Citi’s Mr Chauvet agrees. “In uncertain times, high jewellery can be more resilient than lower-priced fine jewellery price points, thanks to its strong artistic dimension and store of value characteristics,” he says. At auction, Ms Chao’s pieces historically have performed well, with many fetching double or more their estimates.

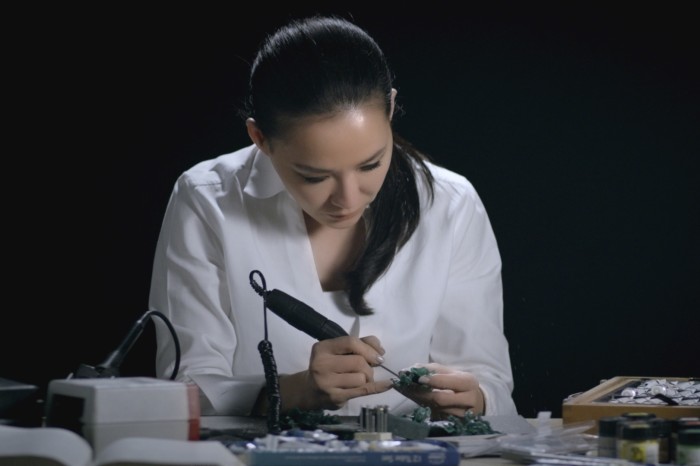

That was not always the case. Ms Chao recalls her first five years as a “struggle” to make her designs a reality, trying to combine her eastern architecture with western craftsmanship. A break came in 2010, when her Royal Butterfly brooch — set with 2,328 gems totalling 77 carats — went into the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s collection. It was the US museum’s first piece by a Taiwanese designer.

More international recognition followed, including exhibitions at the prestigious Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris and Masterpiece London fairs. And this January, Ms Chao’s Ruby Butterfly brooch — set with two intense rubies of 12.89 carats and surrounded by fancy coloured diamonds and colour-changing sapphires — joined the collection at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, again the museum’s first jewel designed by a Taiwanese artist.

It was a notable way to mark 15 years. “Making money was never my purpose to build this brand, but I have to say the first 15 years were ‘create to survive’,” reflects Ms Chao. “As we enter the next 15, my status and mindset will very much be ‘create for creation’.”

Comments