Why jewellers develop new cuts for diamonds

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

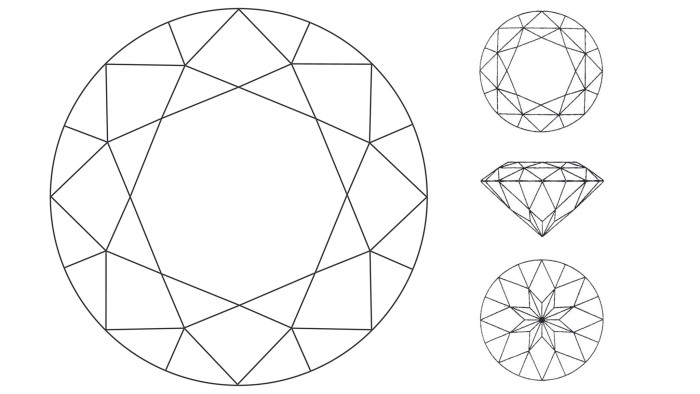

When shopping for jewels, rarely will you be sold a round diamond. Instead you will buy a round brilliant diamond — the additional adjective refers to a cut invented in 1919 by Marcel Tolkowsky, which changed the way diamonds sparkled and how jewellers marketed them. A century later, however, we are witnessing the emergence of a generation of new cuts.

Tolkowsky’s modern round brilliant cut was revolutionary. With 58 facets plotted to ensure maximum light return, it offered a fire and brilliance — that play of rainbow colours and icy scintillation — unrivalled by older cuts. By the mid-century, most new diamond jewellery had moved to this style of faceting, according to the Gemological Institute of America.

The round brilliant remained largely unchallenged until the turn of this century, when price wars caused by the emergence of online-only diamantaires offering rock-bottom prices forced innovation. High-street jewellers with expensive overheads could not compete on price in terms of carat, clarity and colour alone and so manufacturers decided to tweak the final of the Four Cs: the cut. They invented premium-branded stones that promised additional sparkle through extra facets.

“The millennium brought in a flurry of signature diamond cuts,” remembers Willie Hamilton, chief executive of the Company of Master Jewellers, a network of independent jewellery retailers. One reason for this flurry, according to an industry executive, was as a gesture to mark the new era with the permanence that a diamond suggests.

Mr Hamilton’s organisation joined the trend, creating Mastercut, a brand of jewellery exclusive to the group that claims to deliver 30 per cent more brilliance by supersizing the facet count of its round brilliant diamonds to 89. “The average spend on a diamond engagement ring in the UK is still below £1,500, which means manufacturers are constantly complaining about falling margins,” he says. “When this squeeze happens, manufacturers have to start looking at added value rather than simply trying to cut back on costs . . . By introducing special cuts and branded diamonds, this can be done, but it takes considerable investment.”

Many of the brands that offered modified round brilliant cuts have since disappeared from the high street, begging the question of whether it was simply a gimmick. “In my view, extra facets alone are a marketing stunt and should be treated with suspicion,” says Andrew Coxon, president of the De Beers Institute of Diamonds. “The truth is that extra facets alone do not guarantee extra sparkle. The alignment of each facet is much more crucial. Making major facets smaller by dividing them up and increasing their numbers often results in less sparkle, not more.”

De Beers Diamond Jewellers, the retail arm of the mining corporation that was set up as a joint venture with LVMH, did offer a patented cut when it first launched in 2001, an eight-sided square diamond, but the concept failed to catch on, Mr Coxon says: “In our experience, shoppers may enjoy looking at novelty cuts, but they usually buy beautifully aligned classic cuts that sparkle strongly from every angle and in all light conditions.”

Other millennial cuts have endured. Like De Beers, Tiffany & Co and Garrard chose to develop bespoke fancy cuts (a fancy cut is anything other than a round brilliant diamond) in time for the year 2000 rather than simply modifying round cuts. Tiffany’s trademarked Lucida square cut was launched in 1999 and is still a cornerstone of its bridal offer, as is Garrard’s Eternal cut. This is an 81-facet blueprint for brilliance devised by Gabi Tolkowsky, Marcel’s great-nephew, that can be applied to a variety of cuts such as marquise and hearts as well as rounds.

It is in fancy cuts that the latest innovations are focused, but this is a far pricier endeavour than tweaking the modern round brilliant. “It has been challenging,” admits Jonathan Kendall, global operations director at Forevermark, a De Beers retail brand, which has this year launched the Black Label collection of modified fancy cuts. “We’ve put a huge amount of resources into developing these cuts. We have 60 or 70 scientists in Maidenhead working on diamond projects — very few people in the industry have that capability.”

While the process of developing the Black Label collection is scientific, the result is not meant to be about the facet count or a percentage of extra brilliance. “A lot of people talk about light performance and charts and measurement tools, but the reality for the consumer is that they want to have the most beautiful visual diamond they can have,” Mr Kendall says.

The Black Label collection has five shapes to date — a cushion, a heart, a square, an oval and a round — although Mr Kendall hints there may be more to follow. Despite prices for Black Label’s fancy cuts being 30 per cent more than its standard fancy cuts — partly because of increased wastage from the process — this year’s soft launches in the US, Japan, China and the UK have been well received. The most popular is the oval cut, the initial run of which sold out within four months of the launch, leaving retailers waiting for stock. “I’m not surprised, really,” says Mr Kendall. “The industry is desperate for innovation in both jewellery design and diamond cuts.”

Yet for some jewellers — and their customers — value for money comes second to beauty. Nirav Modi, which opened a store on London’s Bond Street this year, has developed four patented cuts. “I think it captures the imagination,” says founder and creative director Nirav Modi. “When you have something new, something different to offer, clients are interested.”

While its floral-inspired Jasmine and Mughal cuts are the most popular, Mr Modi is proudest of his Endless cut, which curves diamonds so that a series of them can be fitted around the finger creating a continuous diamond ring with no visible metal setting. “It is incredibly difficult to do — diamonds do not come in that shape so the yield is very low, 85 per cent of the rough is lost,” says Mr Modi, who harboured the dream of this cut for 20 years. Fittingly, for a labour of love, the first Endless ring created was a gift for Mr Modi’s wife.

Whether or not any of these 21st-century cuts will challenge the supremacy of the modern round brilliant, they are keeping the art of the lapidary at the cutting edge.

Comments