How China is targeting Big Tech

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

At the start of the year, Alibaba’s internal bulletin board buzzed with questions from staff as China’s antitrust officials began formally investigating the tech giant.

But the company’s executives had no answers for many of the questions. China’s tech industry had never experienced serious enforcement of the country’s competition laws.

Staff said the regulators had interviewed them and downloaded chat records from Alibaba’s internal communications platform. The officials had the power to take whatever data they wished, extending to surprise raids that could halt operations. As the investigation unfolded, executives told staff they had studied antitrust cases in the EU and US to prepare themselves.

The sudden burst of activity from the State Administration of Market Regulation (SAMR) has rattled the tech sector.

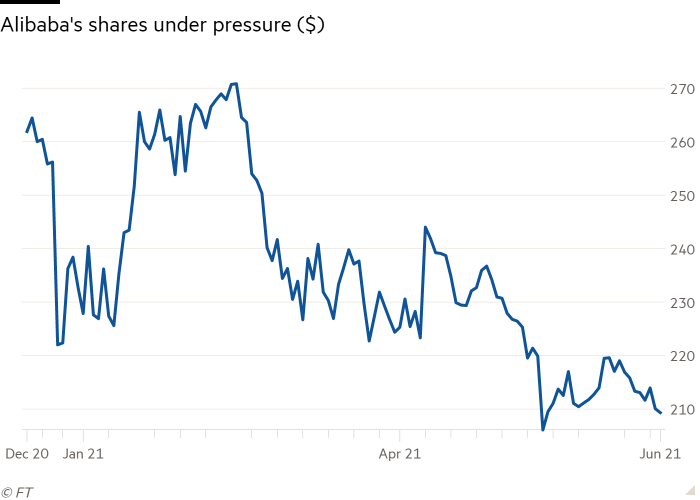

Alibaba’s shares are down about 18 per cent since it came under investigation in December, and have not rallied significantly even after regulators concluded their initial case with a $2.8bn fine. The food delivery company Meituan has slipped about 5 per cent since it became the second target of a formal probe at the end of April.

Over 30 other tech companies have also been asked to undergo “self-rectification” and to provide information to SAMR, including the ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing, raising uncertainty ahead of its planned blockbuster US IPO.

“It’s the speed of the U-turn that has surprised everyone: in China, regulators can move very quickly. In fact, China is catching up to the regulatory norms of the US and EU — the direction is right,” said Daisy Cai, head of the Beijing office of venture capital firm B Capital.

Public anger is driving cases

Lawyers and tech insiders said the wave of antitrust activity had come partly in response to public anger over the enormous power of some tech companies, such as online grocery platforms and food delivery companies, which became essential utilities during the coronavirus pandemic, but had not shared the proceeds with their overworked delivery drivers.

Beijing’s goal also appears to be to rein in the most high-profile tech billionaires such as Jack Ma, the outspoken founder of Alibaba whose Ant Group IPO was pulled last year, and to refocus companies on serving society and the government’s ambitions.

“No matter whether it’s the antitrust law or the anti-unfair competition law, for the government these [laws] are all tools for social governance. They’re all for setting standards of behaviour, and what is most effective will be used,” said Wei Shilin, a lawyer at Dentons.

Enforcing competition law was not just about improving the market, agreed Guo Shan, at Plenum, a Beijing consultancy, since the authorities were looking closely at fintech and worker treatment. “Antitrust could be a useful tool to keep these tech giants disciplined,” she said.

In March, Li Shouzhen, a member of China’s government consultative committee, told state media that China was shifting from the “inclusive and cautious regulation” under which its tech giants had been allowed unfettered growth to “science and innovation regulation”, with a focus on protecting consumers and tech start-ups from the established giants.

Beijing also wants its tech companies to carry out foundational research, to help it in the long-term tech decoupling with the US, rather than just to focus on attracting as many consumers as possible to their platforms.

Regulators lack resources

But in many ways, the antitrust regulators are outmatched by the size of China’s tech companies. As of March, SAMR only had a staff of about 50 people, according to Huang Yong, a member of the State Council’s antitrust consultative committee.

It does not have a separate team of economists to analyse cases, and instead contracts private consultancies or academics on occasion, according to Fay Zhou, head of Linklaters’ China competition practice. Meanwhile, the tech companies have been busily hiring lawyers, and government relations staff, to try to shield themselves.

The current antitrust campaign may help SAMR expand itself, predicted Angela Zhang, a law professor at the University of Hong Kong and author of Chinese Antitrust Exceptionalism.

“Chinese government departments at all levels relentlessly compete for policy control,” she said. “The antitrust regulators definitely see the current campaign against Big Tech as the perfect opportunity to step back into the limelight, allowing its small bureau to request more budget and personnel.”

The sharpest stick that SAMR has is the antitrust law, which allows for fines of up to 10 per cent of a company’s domestic annual revenue, the same penalty proposed by the EU’s Digital Markets Act.

But investigations under this law can be slow, and its main purpose is deterrence, said Wei. SAMR is tackling several anti-competitive practices by the tech companies, including forcing merchants to be exclusive to one platform, which was the headline reason for Alibaba’s fine, price gouging after luring customers with discounts, and offering different prices to different customers.

Yet many of these behaviours are difficult to define and prove, and SAMR lacks resources to go after all of the companies involved in such behaviour, lawyers said.

Tech companies start to polish public image

Instead, regulators are focusing on companies whose behaviour results in public outcry. “Companies can watch out for complaints from consumers, clients, and the media,” said Zhou. “When a company’s behaviour becomes elevated to the level of a public dissatisfaction, the risk of regulatory inquiries or even intervention would be high.”

Companies that attract the attention of regulators can expect a long period of private negotiation and communications before anything is made public — if the case becomes public at all.

In response to the pressure, China’s tech founders have started to court public opinion by stepping up their pledges to improve society. In April, Tencent said it would spend Rmb50 billion ($7.7 billion) in social and environmental initiatives. Pony Ma, Tencent’s founder, also pledged $2bn of his shares to charity.

Other tech executives are stepping out of the limelight, including Colin Huang at Pinduoduo, who said he wanted to do scientific research, and Zhang Yiming at ByteDance, who spoke of “giving back to society”.

Biggest blow will be tighter rules on data

It remains unclear how badly China’s tech companies will be hit by the enforcement of the rules. After it announced its antitrust fine, Alibaba said its revenues would grow 30 per cent year on year to Rmb930bn. Meituan’s chief executive has assured investors that the company was likely to hang on to its merchants and has not altered any growth targets.

Daily newsletter

#techFT brings you news, comment and analysis on the big companies, technologies and issues shaping this fastest moving of sectors from specialists based around the world. Click here to get #techFT in your inbox.

Oliver Rui, professor of finance at China-Europe International Business School in Shanghai, warned that tighter controls over data collection would be the top risk for the companies — much as Apple has hurt the global advertising industry through tighter controls on tracking.

Investors remain confident in backing the current industry leaders. “These companies are leaders because they have built steep competitive moats. Their platforms still have significant centralising power, and they will continue to be the leaders,” added Cai, the venture capitalist.

Additional reporting by Nian Liu

Comments