How to invest in emerging markets

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is president of Queens’ College, Cambridge, and an adviser to Allianz and Gramercy

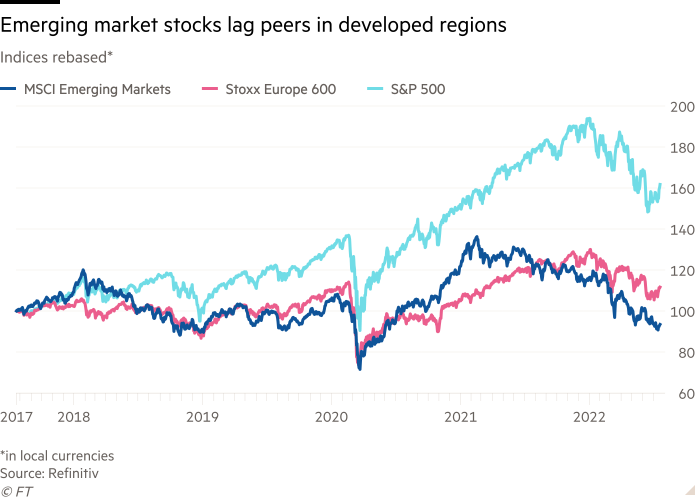

After eye-popping price drops in the first half of the year and a bit of a bounce in recent weeks, more analysts are recommending higher across-the-board exposure to emerging market assets.

After all, the valuation metrics for these markets are at historically cheap levels if you look at indices, both on a standalone basis and relative to developed markets. The bulls argue that, with most disruptive forces now in the rear-view mirror, a period of lower volatility and higher returns is immediately ahead of us.

Cheap historical pricing is, in my view, a necessary but not sufficient condition for gainful emerging markets investing, particularly for those with little appetite for volatility.

Investors need to take into account both the dispersion of returns within the asset class and economic and financial influences that are yet to play out fully, such as the surge in global inflation forcing major central banks to tighten policies aggressively into a rapidly slowing global economy. And some securities face significant restructuring risk (that is, price drops that are not recoverable with time).

A strong general case for emerging markets exposure needs the big macro threats, or what economists call common global factors, either to lift or to be better reflected in valuations.

Remember, this is a tricky operating environment for emerging economies, particularly commodity importers. Heightened food and energy insecurity is compounded by slowing global demand, dollar appreciation, a tightening in capital markets’ financial conditions and a tougher landscape for official bilateral aid.

Some have argued that this was already reflected in the high volatility and negative returns of the first half of this year. But this assumes that, from here, four factors will not prove problematic.

Specifically: that systemically important central banks, led by the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, will be able to battle inflation without tipping their economies into recession; that inflation itself will not prove sticky; that more “tourist investors” who have ventured well beyond their normal habitat (and benchmarks) will not take flight; and that the internal social and political fabric of countries will be able to absorb a significant hit from prices of food and necessities.

These are not the only assumptions being made by those advocating higher, across-the-board exposure to emerging markets. They are also assuming that, for the most financially-fragile economies, official creditors including the IMF and the World Bank will willingly repeat the burden-sharing disappointments of 2020.

To help ease the burden of Covid-related emergencies, they provided significant assistance to emerging countries on the assumption that private creditors would follow suit. Yet the implementation of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative and the formulation of the Common Framework for debt treatment by the G20 were not matched by similar efforts from private sources. If official creditors were to pull back, the lack of aid and debt relief would increase the likelihood of painful cuts in spending on social sectors, aggravate the headwinds to climate change alleviation, fuel greater inequality, and damage actual and potential growth.

This is not to say there are no attractive emerging markets opportunities. But rather than general investing by tracking indices or putting funds in ETFs, investors should focus on selective opportunities with collateral — either assets pledged to creditors or implicit in form such as very large cash cushions or, in the case of sovereigns, large international reserves.

Investors should look to acquire good names that have been hit by typical emerging markets technical contagion, distressed assets where recovery values are high and those contaminated by domestic financial market failures.

The realities of economic management also underline how investors need to be aware of the sequence of likely events in emerging markets. Faced with high import prices, declining demand for exports and low international reserves, countries tend to opt for currency depreciation to help in financial adjustment and economic restructuring. For several of them, this will keep domestically denominated securities at an inherent disadvantage compared with those issued in hard currency.

The time will come for across-the-board exposure to emerging markets. For now, a more selective approach is in order, including via private markets. Investors, though, should be prepared for more bumps in the journey to higher returns.

Letter in response to this article:

Emerging markets are people, not just numbers / From Jim Sanders, Elizabethtown, PA, US

Comments