Asset managers in $300bn drive to build private lending funds

Simply sign up to the Fund management myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Asset managers are seeking to raise almost $300bn to plough into private lending deals with groups such as Goldman Sachs and Oaktree hoping to lure investors away from frothy public markets.

Publicly traded debt and equity securities have surged in price this year after central banks and governments across the world unleashed trillions of dollars worth of stimulus to dull the economic blow from the pandemic.

Managers argue that private credit — including funds set up to lend directly to companies — is one area that has not yet become saturated. It has also benefited from post-financial crisis regulations that pushed banks to tamp down lending to riskier clients.

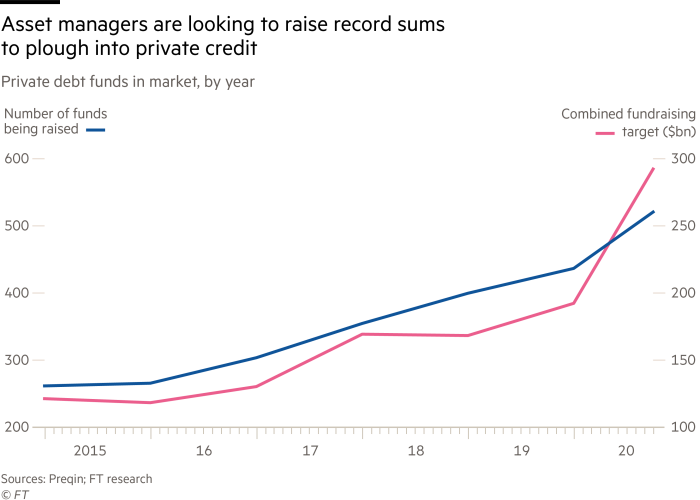

The rush into the sector has been swift. Asset managers were pitching 520 private credit funds to investors in October, up from 436 at the year’s start and just under 400 in January 2019, according to data compiled by Prequin and the Financial Times.

And managers are targeting ever larger amounts. Average fund sizes have swelled, with the combined fundraising target sitting at $292bn. That is up from $192bn in January.

“At this stage of the credit cycle, there will be private market assets that are interesting and can deliver strong returns for investors,” said Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at BlueBay Asset Management. The firm is focused on distressed debt opportunities in emerging markets and among companies.

Goldman Sachs is looking to raise $14bn for its West Street Strategic Solutions Fund I, above the $5bn to $10bn target it had first set out. Oaktree, the investment group founded by Howard Marks, is raising a $15bn fund to invest in distressed corporate credit. And other big funds, including the $9bn private credit fund recently secured by the investment group HPS, are at work to write big cheques to medium and large-sized companies.

Fund managers are racing to raise money for private lending

$14bn

what Goldman Sachs is looking to raise for its West Street Strategic Solutions Fund I, above its original $5bn-$10bn target

$9bn

the amount recently secured by HPS in closing out one of the biggest-ever private credit funds

$12bn

Apollo’s new direct lending partnership with the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund Mubadala

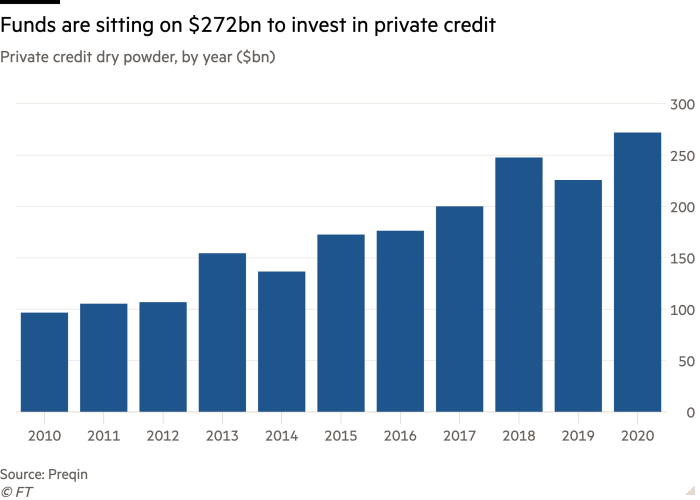

Asset managers are already sitting on more than $2.6tn of so-called dry powder, money they have raised to invest in leveraged buyouts, private debt, real estate, infrastructure and natural resources, the Preqin data show. That figure is double the level that had been raised just six years previously.

Many investors have been pushed out of haven investments including Treasuries, as yields have collapsed to record lows this year, following the Federal Reserve’s move in March to cut US interest rates to near-zero. Some have pumped their cash into higher yielding “junk” bonds instead.

But even in that riskier corner of the market, the potential returns have dropped. Yields on junk bonds — which move inversely to prices — have slid from more than 11 per cent at the nadir of the market dive in March back towards 5 per cent, according to Ice Data Services, even as investors weigh up the viability of some lowly rated borrowers.

“We’ve been in a prolonged zero or low rate environment with 80 per cent of fixed-income assets today yielding less than 2 per cent,” said John Zito, Apollo’s co-head of global corporate credit. “So I think it’s natural that institutions, especially those managing long-term liabilities, are committing more capital to private credit to seek longer-dated excess yield.”

Still, many companies have already sold equity or borrowed through bond markets to shore up their financial reserves, providing one challenge to the new wave of private credit funds: where to put their new money.

Hanneke Smits, chief executive of BNY Mellon Investment Management, told a conference last week that there were limits to “the amount of capital that private equity and private debt markets can absorb”. Ms Smits said that would “limit returns in the future”.

Comments