Five takeaways from the UK’s levelling-up plan

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

More than two years after Boris Johnson came to power with a promise to “level up” the UK, his government published a policy prospectus on Wednesday on which it intends to be judged by voters at the next general election and beyond.

In a 332-page document delivered by Michael Gove, the levelling-up minister, the government sought to crystallise a policy agenda that critics say has remained stubbornly ill-defined since the prime minister took office two years ago.

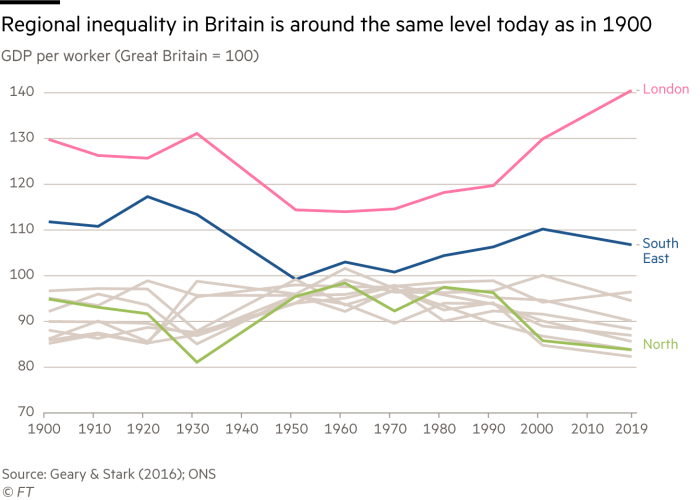

The paper promised to tackle the UK’s long-entrenched regional inequalities through a programme of English devolution, targeted spending in poorer areas outside London and the South-East, and 12 medium-term “missions” against which to benchmark success.

Here the Financial Times offers five takeaways from the levelling-up white paper, and assesses whether the policy plan will meet its promise to transform Britain’s economic and social geography.

Deepening English devolution

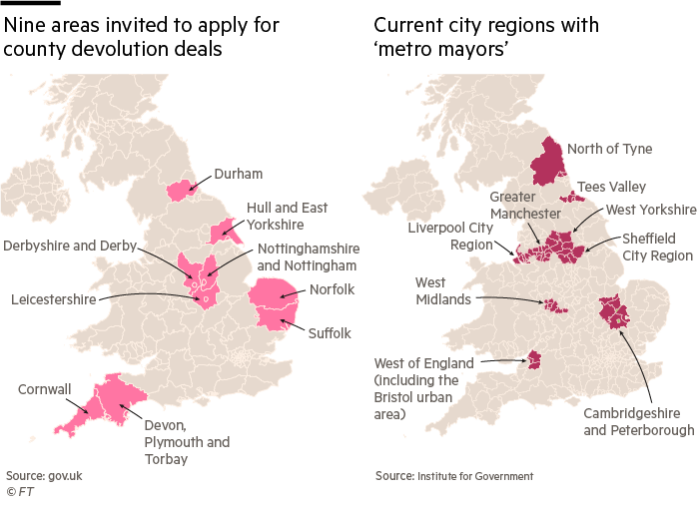

At the heart of the proposals is a pledge to hand more powers from Whitehall to the English regions, building on the popularity of prominent metro mayors such as Andy Burnham in Greater Manchester and Andy Street in the West Midlands.

Nine areas in England will be invited to apply for so-called “county deals” that transfer powers to local authorities in sectors such as transport, housing and skills. Greater Manchester and the West Midlands will be invited to negotiations to deepen their existing powers.

Meanwhile, regional directors will be appointed to act as a conduit between central and local government, with every part of England that wants a “London-style” devolution deal to receive one by 2030.

The devolution plans build on those of former Conservative chancellor George Osborne announced in 2015, extending the offer to more places and adding clarity on what is required to win a deal.

The proposals were widely welcomed by regional and local government leaders, with the caveat that they would only work if backed with enough funds and commitment from the government to drive through the changes.

With those conditions, Tim Oliver, chair of the County Councils Network, said the commitment to county devolution deals could be “a game-changer”.

But Jonathan Carr-West, chief executive of the Local Government Information Unit, a think-tank, said elected mayors and county deals “cannot drive levelling up unless they are full partners in that enterprise”, rather than being “kept dependent on Whitehall for funding and approval”.

Transport, infrastructure, housing and connectivity

Government spending will be redirected to poorer areas that were disproportionately hit by a decade of austerity cuts to public spending.

For example, a Treasury rule which currently stipulates that 80 per cent of funding by Homes England, the public housing body, must go towards the most unaffordable parts of the country — London and the South-East in practice — will be scrapped.

Some of the money that would have gone to affluent areas will probably go into a £1.8bn fund for regenerating brownfield sites in the North and Midlands. Previously announced money will also be directed towards improving local bus networks.

The paper promised projects to regenerate derelict urban areas in 20 towns and city centres, including Wolverhampton and Sheffield, as well as to help 68 further local authorities to revitalise their high streets.

Campaigners asked if enough cash was available to narrow the gap between London’s £882 annual spending per person on public transport and the England-wide average of £393.

“It feels like a lot of slogans and not a lot of substance,” said Norman Baker of Campaign for Better Transport, an advocacy group.

John Baker, co-founder of homebuilder Modomo, said the government risked “overpromising and underdelivering” by spreading funding too thinly.

Skills revolution

As well as physical infrastructure, the paper argued that building social infrastructure through better provision of regional skills would be at the heart of its ambition.

It pledged to improve child literacy and numeracy in the areas where it was weakest, and to improve workforce readiness by requiring employers and colleges to collaborate on plans to match skills to the needs of industry.

Lisa O’Loughlin, principal of Manchester College, said the commitment to give local colleges and chambers of commerce more control over courses could be a radical change.

Others were sceptical that the plans would be well enough resourced to make up for a decade of cuts to further education.

Stephen Evans, chief executive of the Learning and Work Institute, a think-tank, said the mission for 200,000 more adults to gain qualifications by 2030 would only reverse one quarter of the falls in adult learning since 2010.

He added that investment in skills would remain £750mn lower in 2025 than in 2010. “Whilst the metrics provide direction, unfortunately the white paper falls short on all counts,” he said.

David Hughes, chief executive of the Association of Colleges, said that while local decision-making was welcome, an overarching strategy to tackle countrywide skills gaps in sectors such care or construction was missing. “Those truly national priorities will need to have a national framework.”

Research and innovation

The government will look to ensure that regions outside London and the South-East benefit more from a planned expansion of state spending on research and development to £22bn a year by 2024-25.

The paper also pledged to increase public R&D investment outside the so-called “golden triangle” of Oxford, Cambridge and London by “at least 40 per cent” by 2030.

On top of these general commitments, the business department will spend £100mn over the next three years on three new “innovation accelerators”. These will be based in Greater Manchester, the West Midlands and Glasgow.

Scientific leaders said geographical rebalancing of R&D “needs new investment and not just a repackaging of old money,” as Sir Adrian Smith, president of the Royal Society, put it.

“We cannot afford to ‘rob Peter to pay Paul’ by investing in some localities at the expense of world-leading research in already hugely successful research clusters,” he said.

Staying on track

Alongside listing 12 medium-term “missions” for levelling up, the government promised to develop other “supporting metrics” using Office for National Statistics data. Local and central government departments will use these to track progress on the 2030 goals.

The missions will set targets to increase productivity, narrow gaps in healthy life expectancy, raise the number of first-time buyers, provide better housing and widen educational opportunities.

Will Tanner, director of the Onward think-tank, which has contributed much to Conservative thinking on levelling up, said the metrics would make targeting regional growth “the rule, and no longer the exception to the rule,” in Whitehall policy planning.

Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said that by setting long-term goals, the government was “transcending normal political timescales”, but warned that many of the goals looked “extremely ambitious — that is to say, highly unlikely to be met, even with the best policies and much resource”.

Creating a “globally competitive” city in every region would be a stretch, given the current gap between London and the most productive northern cities, for example, as would increasing productivity across the country after a decade’s stagnation.

Progress will be monitored by a new levelling-up advisory council, an independent body created to improve transparency around local authorities performance, and a legal responsibility on government to report on progress towards the missions.

Reporting team: Peter Foster, Delphine Strauss, Bethan Staton, Clive Cookson, George Hammond, Harry Dempsey and Sarah Neville.

Cartography by Liz Faunce

Comments