What can a Buddhist monk tell us about business?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

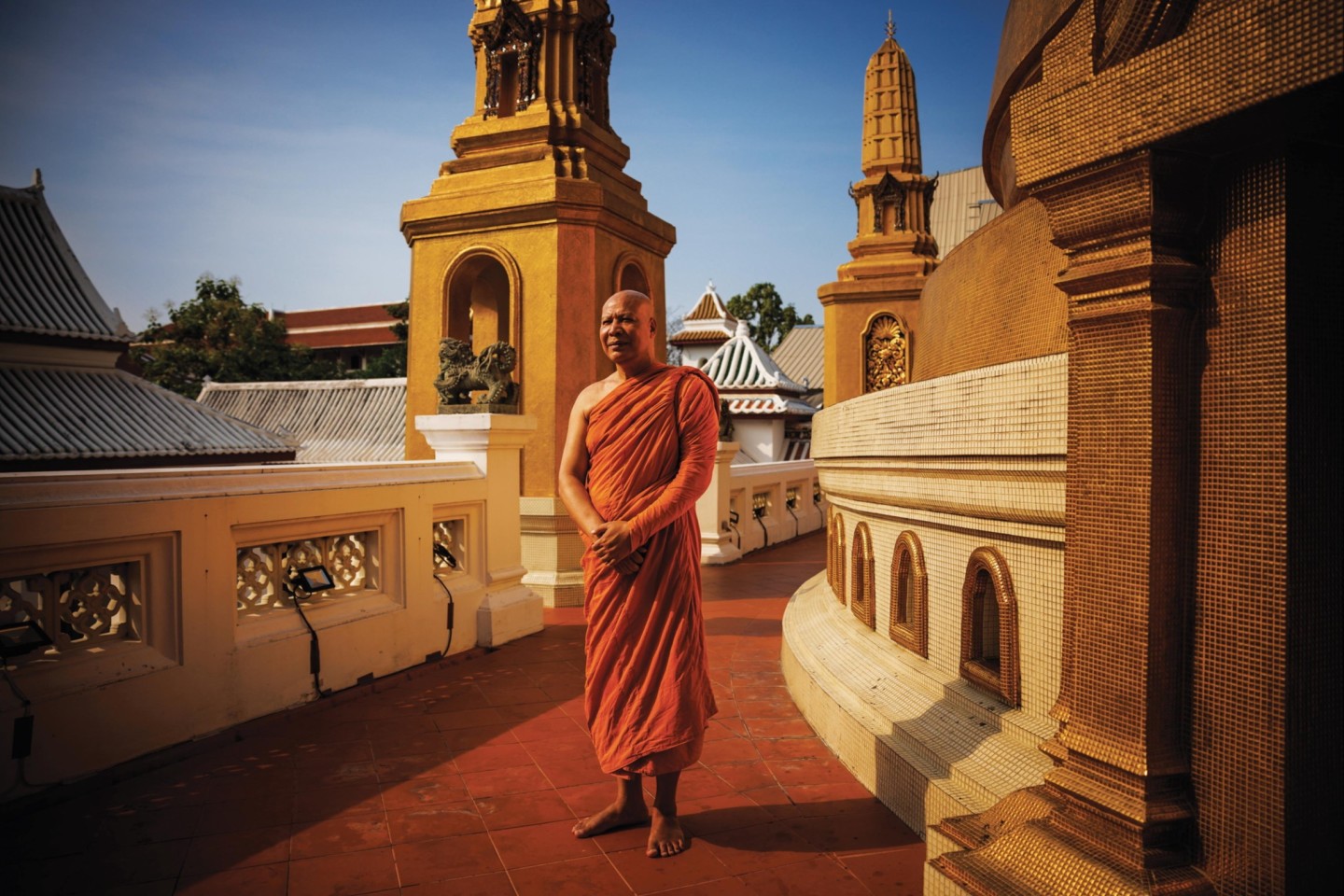

Phra Anil Sakya, one of Thailand’s most senior Buddhist monks, teaches mindfulness to business executives and to criminals. In Rayong Central, a high-security prison with more than 7,000 inmates, his mindful cognitive therapy programme has an impressive record. Overall, a third of prisoners released from Thai prisons reoffend and are jailed again within three years but, according to Phra Anil, nine out of 10 inmates who do his course never return.

“I asked one murderer who had been paid to kill his victim, why?” Phra Anil recalls of one exchange. “He told me, ‘Venerable Sir, because killing is my job.’ Being mindful is knowing what is wrong or right for humanity, so when I speak to business executives, I teach them they have to put people before profit. Mindfulness is coming back to who you are, changing yourself first before trying to change others.”

The teaching of mindfulness — paying attention to the present moment — and self-awareness is a growing trend in executive education, as schools seek to help business leaders appreciate and adopt more reflective, analytical and collaborative styles of decision-making and management. After all, the rationale goes: how can you lead others if you don’t know how to lead yourself?

As a result, Phra Anil is a regular speaker on executive education programmes at Sasin School of Management in Bangkok. School director Ian Fenwick, who recently installed a meditation room, says: “In Thailand, we have an advantage because of the tradition of Buddhism. Many executives are used to going to the temple and spending quiet time.

Financial Times Executive Education rankings 2023

View the twin main rankings of custom and open-enrolment executive education programmes, plus the combined top 50 table.

“If we replace the word ‘mindfulness’ with ‘reflection’, it becomes a lot more approachable. We’re simply encouraging people to take time out and to reflect, abstract from the immediacy of the situation and look at the decisions they have to make from more of a distance,” Fenwick adds.

Encouraging reflection is not a new discipline in executive education. More than a quarter of a century ago, Canadian academic Henry Mintzberg helped launch the International Masters Program for Managers (IMPM) at five universities around the world. The one-year course, which takes executives to Japan, Brazil, India, Canada and the UK, seeks to refocus business education around five mindsets, including the “reflective mindset”, taught at Lancaster University. Executives visit local Quakers to appreciate an alternative sense of self and learn their style of decision-making and management. Walking, poetry and canoeing are also part of the experience.

“We think of mindfulness and reflection as more of a social and collaborative practice, rather than some kind of meditative, stepping out of the world,” explains Martin Brigham, IMPM academic director and associate professor at Lancaster University Management School. “Many executives make decisions in an unthinking way, like we change gears in a car. Reflection is a way of making you think about your thinking rather than just thoughtlessly doing whatever you’ve done in the past. The four most important words in business? ‘What do you think?’”

Brigham cites one alumnus, Abbas Gedi Gullet, who ran refugee camps for the Red Cross in Kenya. After completing the programme, he persuaded the organisation to invest in a different kind of accommodation — luxury hotels — and plough profits back into the charity. “Through reflection, he was able to flip the mindset,” says Brigham. “Managers like to fix things, but sometimes they also have to challenge the philosophy on which their actions are based.”

Mindfulness and reflection aren’t only for the boardroom. Researchers at the University of Exeter Business School found that, in particularly monotonous roles, employees who are more “mindful” have greater satisfaction and are less likely to quit or think their job is boring.

More than half of US employers offer some form of mindfulness training to workers, according to a survey by Fidelity Investments and the Business Group on Health. Free subscriptions to meditation apps Calm and Headspace are among the post-pandemic workplace benefits offered by large companies including Starbucks. Drinks maker Diageo’s new London offices include a whole “wellbeing” floor and a studio that runs health and wellness sessions including mindfulness and meditation.

Yet, while studies have shown that mindfulness can improve self-esteem, reduce anxiety and help manage depression among many employees, psychologists have also warned that, for a small minority, some mindfulness practices can have an opposite effect, making people more anxious, even to the point of panic attacks. So, with many business schools rushing to add mindfulness and reflection to their syllabuses, how can executives discern what is promotional fluff or even counterproductive from what is genuinely effective?

“It’s our responsibility to use thoroughly researched, scientifically proven tools, methods and concepts,” says Tom Lindholm, managing director at Finland’s Aalto University Executive Education. Aalto’s programmes include a built-in personal development process designed to enhance self-development and self-awareness.

“Some of our executives report feelings of an invisible support growing inside them, giving them strength, confidence and calmness,” Lindholm says. “Others say they are now able to find solutions to difficult challenges, where before they felt helpless, waiting for someone else to come up with answers.”

While some executives might be more naturally inclined towards self-reflection and mindfulness, these are competencies that can be taught, argues Tore Hillestad, director of executive education at NHH Norwegian School of Economics, which works with leadership and organisation development consultancy AFF to offer mindfulness training. “We integrate what is learnt on the programme into daily behaviours, in a repeated and systematic way. If taught well, it’s no fluffier than developing hard skills like familiarity with a new tool or software.”

Back in Bangkok, Phra Anil suggests his own simple mindful habit. “Just try closing your eyes, shutting yourself down and living in the present. Bring things back to yourself and ignore the impulse to check social media and look at others’ lives. Do not forget to look at your own life.”

Comments