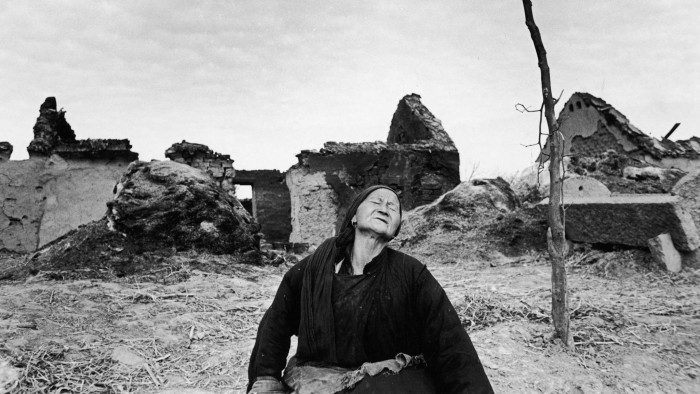

‘The Tragedy of Liberation’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution 1945-57, by Frank Dikötter, Bloomsbury, RRP£25/$30, 400 pages

Some histories have considered the period 1949-57 to be the closest that Maoist China came to achieving a “golden age”; or gilded, at least, relative to what would follow. They credit the Communist party with creating in the early 1950s a consensus leadership and centralised state after a traumatic century of invasion and civil war; with rebuilding and reindustrialising the economy; and with enabling China to “stand up” by fighting the US army to a stalemate in Korea. “Had Mao died in 1956,” one of his colleagues speculated after the Chairman’s demise, “his achievements would have been immortal.”

In The Tragedy of Liberation – a prequel to his Samuel Johnson Prize-winning Mao’s Great Famine (2010) – Frank Dikötter convincingly demolishes this rosy assessment of the early People’s Republic. “Violence was the revolution,” he observes, as he describes how Mao Zedong and his lieutenants created a “one-party state that sought to control everyone but answered to nobody”. In Dikötter’s account of Chinese communism between 1945 and 1957, the devastating famine of 1958-62 and the vicious purges of the Cultural Revolution that began in 1966 are cataclysms waiting to happen. The state-sanctioned savagery and fanatical meddling that would make both these later events possible are already clearly visible.

Dikötter, a Dutch historian who teaches at the University of Hong Kong, begins with the immediate historical background to Communist rule: the ruthlessness with which Mao’s generals waged the four-year civil war that brought the party to power in 1949. Far from reflecting a moral “mandate” to rule, the Communists’ victory against their Nationalist rivals was overwhelmingly military in nature. To conquer key cities in the industrial northeast, Communist commanders laid siege to civilian populations. “Turn Changchun into a city of death,” proclaimed Lin Biao, one of Mao’s most successful strategists, in 1948. By the time the metropolis fell five terrible months later, 160,000 non-combatants had died of starvation.

Soon after the founding of the People’s Republic, punitive taxes paralysed the economy; unemployment soared. The regime had already unleashed an orgy of violence against those labelled members of “bad classes”. Between 1947 and 1952, land reform killed between 1.5m and 2m rural residents categorised as exploiters. “Why,” a group of farmers asked in a 1951 letter to the People’s Daily, “doesn’t Chairman Mao just print some banknotes, buy the land from the landlords and then give us our share?” Mao, Dikötter explains, was set against any such peaceful course; he was determined to use the thuggery of land reform to destroy the complex ties and loyalties of pre-revolutionary Chinese society “so that nothing would stand between the people and the party …Nobody was to stand on the sidelines. Everybody was to have blood on their hands.”

In 1954, only two years after this ferocious upheaval, collectivisation took back the land that the party had just redistributed. The year before, the party had imposed a grain monopoly that forced farmers to sell their crops to the state at fixed, low prices, leaving less than subsistence rations for the growers themselves. Hundreds of millions were reduced, in Dikötter’s powerful term, to serfdom. Years before the great famine began at the end of the 1950s, many were already starving in the countryside.

Campaigns against counter-revolutionaries scarified the cities also: “the killings can absolutely not be allowed to stop too early,” Mao directed from Beijing as he handed out death quotas. In Beijing, he calculated, “killing roughly 1,400 should be enough”. More than 2m urbanites died, Dikötter estimates, in the “Great Terror” of the early 1950s.

This bloodletting set the tone for the rest of the 1950s, as waves of persecution (against merchants, traders, bankers, academics) swept across the country. The Korean war – trumpeted as a grand symbolic victory for communist China against the US – came at hideous cost for the soldiers on the ground, some of whom had to march barefoot in subzero conditions. Civilians, meanwhile, were pressured to finance the war effort. A farmer who pleaded poverty was told: “Dead or alive you will donate” (he subsequently drowned himself). In 1956, Mao invited malcontents to discuss the regime’s shortcomings. Less than a year later, shocked by the intensity of complaints, he turned on his critics. Hundreds of thousands were condemned as “Rightists’’. Many were sent to labour camps where torture and starvation were rife.

The book is a remarkable work of archival research. Dikötter rarely, if ever, allows the story of central government to dominate by merely reporting a top-down directive. Instead, he tracks the grassroots impact of Communist policies – on farmers, factory workers, industrialists, students, monks – by mining archives and libraries for reports, surveys, speeches and memoirs. In so doing, he uncovers astonishing stories of party-led inhumanity and also popular resistance. In one harrowing episode, 104 lepers were locked in a hospital and burnt to death. Elsewhere, farmers who objected to collectivisation hurled urine-filled pots at government officers, sang songs mocking the party and waved banners reading “Down with Mao Zedong”.

Dikötter sustains a strong human dimension to the story by skilfully weaving individual voices through the length of the book. Early on, we meet Dan Ling, a student zealot who grows uneasy at the state’s persecution of alleged enemies; Li Zhisui, a medic who returns to China from Australia in 1949 and eventually becomes Mao’s doctor; and Robert Loh, a patriotic intellectual who escapes quietly to Hong Kong while Mao’s anti-rightist purge approaches its climax. In so doing, Dikötter captures the idealism that motivated many to endorse the revolution and also the way in which the party squandered this enthusiasm.

One of the many tragic aspects of this story is how little possibility China seems to have had of achieving a less brutal government after the second world war. Dikötter is critical of both the forces vying to control the country between 1945 and 1949. The Nationalists rivalled the Communists for callousness during these years; they also chronically mismanaged military operations and the economy, losing the support of urban and rural populations. But rather than emancipating China from conflict, the violence of Communist Liberation in 1949 condemned the country to years more of de facto civil war.

Julia Lovell is a senior lecturer in Chinese history and literature at Birkbeck, University of London. She is author of ‘The Opium War’ (Picador)

Comments