Art fairs in the virtual world

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The abbreviation “OVR”, shorthand for “Online Viewing Rooms”, was barely used in art market circles before the Covid-19 pandemic. It is now almost inescapable.

Originally coined by galleries to describe a dedicated area of their website for registered users, OVRs have effectively replaced art fairs, proving a relatively quick way to pool exhibitors together digitally and galvanise attention. In the eye of the pandemic’s storm, the OVRs that took the place of major fairs such as Art Basel in Hong Kong and Frieze in New York were something of a lifeline for a shuttered industry. “They kept the art world active during a very difficult time and were almost crucial to survival,” says the Milan, London and Hong Kong gallerist Massimo De Carlo.

They have not been universally loved, though — by exhibitors or visitors. It has turned out to be something of a chore to look through dozens of art works on hundreds of microsites, and it is a much more limited and soulless experience than walking around an art fair in real life (which some already found a little tedious). The often-clunky, one-size-fits-all technology has also been difficult for galleries to work with, particularly those with their own higher-spec websites.

So it was something of a surprise when Art Basel announced two new OVRs, outside of their existing fair schedule. First up is OVR:2020, a virtual event for galleries showing art from this year only (September 23-26). Then comes OVR:20c, which runs between October 29 and 31 and is dedicated to 20th-century works. In between those two will be the Frieze London and Frieze Masters OVRs (October 9-16), plus several of the industry’s other fairs that have also opted for alternative online editions. Now that Art Basel has cancelled its real-life Miami edition, this too goes online in December.

Lessons are being swiftly learnt along the way. “There became so much digital fatigue. There was too much material for collectors and it was difficult to come up with something fresh and not formulaic. The best [digital offerings] have been small, compact and very specific,” says the London gallerist Sadie Coles, who — with De Carlo — is on the selection committee for OVR:2020. She suggests thinking of a digital exhibition as “Like an artist’s book, a journey that needs to unfold.” Her gallery’s current online Matthew Barney exhibition, Cosmic Hunt, leads viewers through a map and underlines the effectiveness of this approach.

Art Basel’s newest OVRs, with a maximum of 100 galleries, each with a maximum of six works and in clearly defined categories, seem much more digestible than the previous iterations. Art Basel director Marc Spiegler says that the new fairs could also be more conversational for visitors, with video and Live Chat functions that have been popular on platforms such as Zoom.

“We’re now in a situation where the digital needs to work for the market to work. The more [OVRs] that we do the more we can refine them to find what is right. As with any experiments, some things will work, some things won’t, but you hope that there is more that does,” Spiegler says.

The truth is that it needs to work for art fair organisers too. Art Basel has had to cancel all three of its real-life fairs this year: in Hong Kong, Basel and Miami. Back in July, and before the Miami fair’s cancellation, Art Basel’s owners MCH Group said it expected group-wide annual sales to halve, by between SFr230m and SFr270m ($250m-$300m). The additional OVRs this season will be the first time that the organisers have charged exhibitors — as they would for a normal fair — though each online “booth” costs SFr5,000 ($5,500), compared to between SFr10,000 and SFr112,000 ($11,000-$125,000) at its real-life Art Basel event. Frieze too is charging for its online fair this season (up to £4,900).

It’s baby steps. But Art Basel’s choice of works from 2020 to launch its new product seems a savvy start. “It will make a very fresh platform, the works will come more or less straight from the studio,” De Carlo says. Like most of us, artists have been in isolation this year, and many say they have been more productive and have something new to say. Meanwhile, collectors, who often want art that reflects their own experiences, have shown an appetite for works that respond to the unfolding crisis.

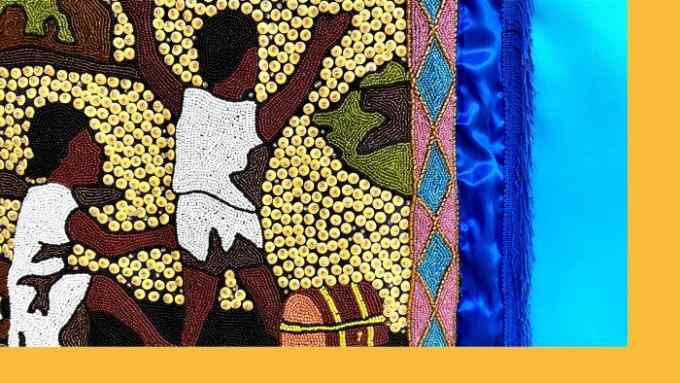

Included on Hauser & Wirth’s virtual booth, dedicated to four of its female artists, are works by Phyllida Barlow who, in the text to accompany her new works on paper, writes of her experience of lockdown in London. She concludes “night and day have become interchangeable . . . ”, something that seems all-too-familiar (works $25,000 each). At Goodman Gallery, collages by Mateo López were made during lockdown in Bogotá using materials lying around from his previous projects (The waste of my time, individual works $16,000 each, full set of five for $68,000).

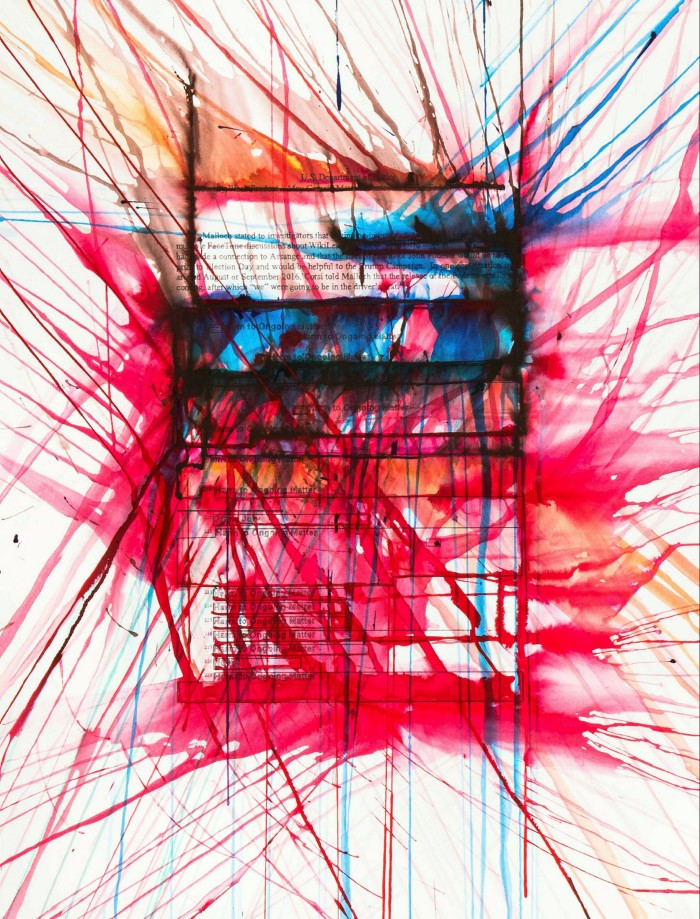

Politics and social unrest, which have also dominated the year so far, can be expected in many of the works and will add some urgency and engagement to an inherently flat platform. New drawings by Jenny Holzer, also at Hauser & Wirth, allude to subjects that currently loom large in the US, with titles including “White House”, “connection to Assange” and “Russian Government’s efforts” (works $55,000 each).

Industry expectations for the incoming revenue from art fairs are not high. In her latest report produced by UBS and Art Basel, the art economist Clare McAndrew surveyed 795 galleries and found that only a third of them expected this already decimated income stream to improve into 2021, while 43 per cent felt they could fall further.

“Are we going to be able to substitute the income from our regular activity — whether fairs, trips to meet people, or other events — in the next eight months? No, that’s not possible,” De Carlo says. He, like many others, recognises however that the digital is here to stay. “We have a new instrument to add to our activity. Galleries and artists need to refine their ways of working and find the best ways to make our businesses more sustainable,” he says. But, he adds, “Do not forget the real world, which is still the best.” Amen to that.

OVR:2020, September 23-26, artbasel.com/ovr

Comments