Interview: Cameron Mackintosh

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Cameron Mackintosh is driving through December drizzle on his 1,630-acre Somerset estate when a grey shape looms across a field, opposite the 13th-century priory where he lives. It is a plaster and polystyrene elephant — 15m high with a howdah carriage on its back — the one in which the street urchin Gavroche sheltered in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. It was built for the 2012 film of the musical that Mackintosh first produced with the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1985.

“It came down on four lorries and it took ages to put together again. The only thing I didn’t think about is that the bloody woodpeckers think it’s a piece of timber. We keep on having to patch it up,” Mackintosh says. He laughs and keeps driving his Lexus crossover along his private roads through the two dairy farms he owns, around hilly bends to two large barns. Inside one, now pristine and air-conditioned, he leads the way to what looks at first glance like a pile of old wood.

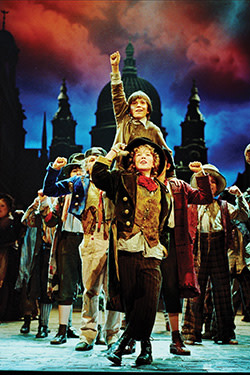

This is the deconstructed set of the 1965 touring production of Oliver!, the Lionel Bart musical on which he worked as an assistant stage manager at 19, while also playing the role of a pot boy. “To Cameron, the man who gets things done,” reads one encouraging message scribbled by an actor on the poster that hangs on a wall in the adjacent barn. Together, the barns contain not only the costumes but the stage sets for his musicals, along with an ever-expanding archive of memorabilia.

We pass racks of costumes for Les Misérables, Miss Saigon and others, and pore over boxes of stage props. Here is another elephant; here an eagle; there a Cadillac from Miss Saigon together with boxed bottles of Saigon beer. Much is still in use on touring productions and storing it here has his signature blend of sentiment and financial logic. He used to rent storage space but his costumes got damp.

As a young stage manager, Oliver! almost finished Mackintosh. His right arm got trapped in a piece of scenery during rehearsals at the King’s Theatre, Southsea, and he was hoisted into the air, nearly slamming his head against a beam. As a producer, it made him. In 1977, he launched a revival of Oliver! and later acquired 50 per cent of the rights. The deal has paid immense dividends — along with his other shows, it has brought him hundreds of millions of pounds.

Since that first revival, when his name was still sewn in the back of the pot boy’s costume, he has produced Oliver! several times in the West End and on Broadway and is working on a remake of the 1968 film. Each year, there are many professional, amateur and school productions and he profits from every one. Like the other big three productions that made him a billionaire — Les Misérables, Miss Saigon and Mary Poppins — Oliver! just keeps going.

No one in the West End or on Broadway — with the possible exception of Andrew Lloyd Webber, his old partner and rival with whom he has a close but sometimes fractious relationship — understands the value of a franchise like Mackintosh. Early in his career, as he was making his name with productions of other people’s shows, the American lyricist Alan Jay Lerner congratulated him on one succès d’estime. “You know what a succès d’estime is, don’t you?” Lerner continued slyly. “A success that runs out of steam.”

With Cats, Les Mis and the rest, Lloyd Webber and Mackintosh created a new category of theatrical entertainment — musicals that never run out of steam. Since 1981, when Cats became a global phenomenon, Mackintosh has become the master of reinvention, pushing the lives of his franchises for decades longer than anyone had previously believed was possible, and extending his grip over every aspect of their exploitation.

“Cameron helped to create the success story of the current West End theatre. His shows have become global earners and proof to the world of the talent and imagination of which Britain is capable,” says John Kampfner, chief executive of the Creative Industries Federation, a membership group for UK arts and creative organisations. “He remains a genuine enthusiast — he wants the whole sector to succeed.”

This does not mean he is universally popular. “He’s very dynamic, very opinionated and very forceful. Those qualities can be constructive, and they can also cause frictions,” says Robert Fox, the West End play producer. “He has a clear view of how things should be and likes people to follow it. It does not always make him loved but I don’t suppose that bothers him. He’s got an enormously kind and supportive side as well as the tough one.”

After five decades of work, Mackintosh is easing off a touch but remains a restless bundle of energy. He is the sole owner of his business, Cameron Mackintosh Limited, which paid him a dividend of £13m last year, and he likes to have a say in every aspect of it. He is cocooned and supported by a coterie of executives who have worked under him for years, sometimes exasperated by his unpredictable whims — “I would never make a bet on what Cameron will decide,” says one — but loyal.

He turns 70 this year and, like Fagin in the Oliver! song, he is reviewing the situation, with some satisfaction. Lounging in an armchair in Stavordale Priory, the former monastery he bought with the proceeds of Les Misérables, he breaks into a warble about his impending birthday. “Must come a time . . . Seventy. When you’re old, and it’s cold/And who cares if you live or you die,” he croons. He halts before the next two lines of the song, “Your one consolation’s the money/You may have put by . . . ”

The money would be quite a consolation, if he did not adore his work. Producing is a risky profession — it is difficult to conjure up a hit and many have gone bankrupt or watched their businesses dwindle as they lost touch with a new generation’s taste. Yet measured in cash, Mackintosh is the most successful the West End has known — he is a mere knight to Lloyd Webber’s baron but his wealth was estimated at £1.05bn in 2015 by The Sunday Times, beating Lloyd Webber’s £650m.

This largely compensates for the likelihood that Mackintosh’s best period as a producer is over — largely but not entirely. He wriggles indignantly in his chair at the idea. “Even very sophisticated people ask, ‘Are you doing anything new?’ But they’re wrong. They’re very wrong,” he retorts, waving both hands. “Look: A, I’ve reinvented all the original hits so they are successful and, B, I’ve done a number of new musicals.” He cites Half a Sixpence, which premieres in Chichester this year. It has been reworked by Julian Fellowes, writer of Downton Abbey, from the 1963 musical based on HG Wells’s novel Kipps.

Still, the last work to join his blockbusters was Mary Poppins, which opened in 2004 after he bought the rights from Pamela Travers, the author, in 1994. Martin Guerre, a musical about a 16th-century French peasant written by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, the team behind Les Misérables and Miss Saigon, closed after two years in 1998. Moby Dick, about a girls’ school musical of the Herman Melville novel, failed in 1993. More recently, he has brought US hits such as Avenue Q to London and will bring Hamilton, the hip-hop musical about the 18th-century founding father Alexander Hamilton, in 2017.

Not being a composer or author, Mackintosh cannot create his own works — unlike Lloyd Webber, whose School of Rock, adapted from the film with a book by Fellowes, has just opened on Broadway to strong reviews. (“Andrew has written an old-fashioned musical. It’s not trying to change the form or anything like that but it’s a good night out,” Mackintosh remarks archly.) He depends on others for ideas he can develop or acquire.

The fact that they are so hard to find is frustrating in one sense but extremely useful in another. It means that top-rank musicals remain rare and so their value keeps rising. “Les Misérables opened 30 years ago and it’s still playing to over 90 per cent attendance,” says Richard Johnston, who manages the eight West End theatres that Mackintosh also owns. “Who knows what the life cycle of these shows is?”

. . .

Mackintosh was born in 1946 in London. His father Ian was an Anglo-Scots timber merchant and his mother Diana, a former secretary, is of Maltese, French and Italian descent. “I started with nothing because there wasn’t anything after the war. I had a loving family and went to a minor public school (Prior Park College in Bath) so, compared with many people, I had a lot, but I didn’t have a trust fund,” he says. “I had to borrow £10 here and £20 there.”

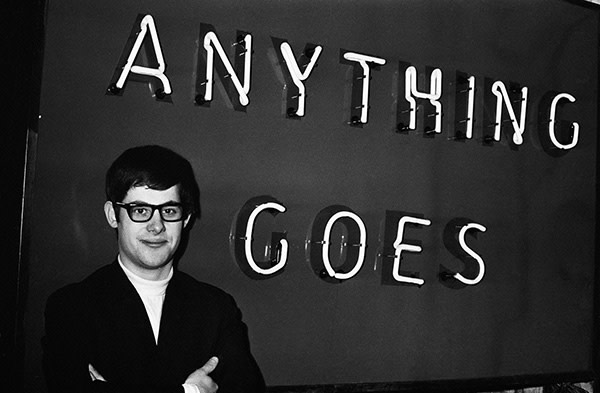

His childhood introduction to the theatre came from two aunts, who took him to the musical Salad Days in the West End. “I didn’t want to go but I was captivated. So when my birthday came, my aunts and mother said, ‘What would you like?’ I said, ‘I want to see Salad Days again.’” He entered the business after school, graduating from stage management to producing regional shows in the 1960s. He produced Side by Side by Sondheim in 1976 and Oliver! in 1977, and then ran tours of the US musicals Oklahoma! and My Fair Lady for the Arts Council.

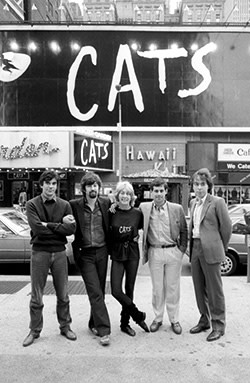

Despite a growing reputation, he was still living in a £5-a-week rented flat in 1980 when, at the age of 43, he met Lloyd Webber for lunch to discuss an idea the composer had for a musical based on some TS Eliot poems. “We were nearly the same age and we had an absolutely pissy lunch at the Savile Club. We were tossed out at about five or six o’clock in the evening. We went back to his flat and he played me some of his settings of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats and I went, ‘Oh, there’s something there.’”

Lloyd Webber was already well known, having composed Jesus Christ Superstar, which opened in 1971, and Evita, which opened in 1978, with the writer Tim Rice. Despite that, it was a struggle to launch Cats. Mackintosh had to woo Trevor Nunn, the RSC director (“One day in October, we were having another of our dinners at Joe Allen’s and Trevor said, ‘I suppose, Cameron, I’ve run out of excuses’”). Money was also hard to come by — Lloyd Webber took a second mortgage to contribute to the £450,000 production cost and Mackintosh rang up the Financial Times, appealing for people to invest.

“The idea of the British doing any musical was fairly risible but doing a dance musical was considered total lunacy. Only Americans did that,” Mackintosh recalls. Unlike on Broadway, where A Chorus Line launched in 1975, West End musicals tended to be plays with songs and few actors were trained to dance and sing. The young Judi Dench had been cast to play Grizabella in Cats but was replaced by Elaine Paige after she tore a tendon in rehearsal. They were fixing the show as it entered previews.

The rest is history — Cats exploded in the West End and on Broadway and the 240 investors in the original London production received £26.8m over its 21-year run, a 60-fold return. “They were people who’d been told, ‘You mustn’t put money into show business — it’s dangerous’, yet they were taking out Post Office savings. I would say, ‘You can’t’ and they replied, ‘We believe in Andrew and Trevor.’” The 68 backers (including one large syndicate) who put up £600,000 for the original London production of Les Misérables in 1985 have made £47m to date — 78 times their money — and are still earning.

Cats broke the mould of musicals in more ways than just becoming an enduring hit. It was global in a way that musicals about the American dream and American guys and dolls were not. Without planning to, Lloyd Webber and Mackintosh had created a show that translated everywhere. The fact that Cats was so unlike conventional musicals produced a further unanticipated benefit — theatres in other countries did not even try to mount their own versions. They asked for the original.

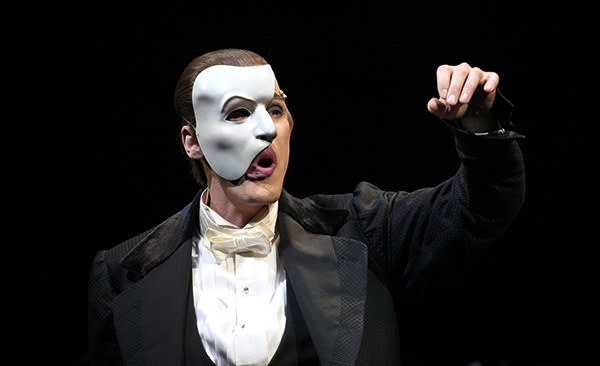

“What used to happen was you’d send them the script and if they paid £3,000 you’d give them the grand plans of the set and they’d do their own version. This time, they were saying, ‘We’d like to do Cats in Vienna or Cats in Norway but we want your production.’” It prodded him into what became his hallmark — making shows look and sound the same in Beijing and Milwaukee as in London and New York. First Cats, then Phantom of the Opera, Les Misérables and Miss Saigon crossed the globe.

The success of those shows spawned a grand rebuilding of US regional theatres, with cinemas being converted to live performance. “When I did Les Mis I said, ‘I’m not going to take this on the road unless it’s as good as what people have read about, with the same lighting and the same sound.’ I think that’s my biggest bequest — that I imposed my standards. It’s sensible, actually, because the real thing will last longer than something shoddy.”

Thirty years later, he constantly restages the same musicals in new productions, with fresh directors and casts. He pulls out a large spreadsheet to display the 47 productions planned up to 2020. “I’ve got six or seven Les Mis’s, three Phantoms, a couple of Cats, four Saigons . . . Two weeks ago, we opened in Brisbane and Korea with Les Mis, and in Japan with Saigon. Mary Poppins was in Bristol and Phantom in the US. And I’m preparing two movies — one of Oliver!, one of Saigon.”

Mackintosh prefers the West End to Hollywood, although the film of Les Misérables was a global hit and won three Oscars. “The downside of films, as I’ve found out, is that they can take vast amounts [at the box office] but you don’t get much of it and you have to do accounting for about five years to work it out . . . I’d rather take £1m in a theatre than £10m in cinemas because I’ll end up with more in my pocket.”

One of his frustrations is that few people appreciate his business, and most heavily underestimate its value. Musicals are expensive to keep running — a top musical has weekly costs of between £150,000 and £250,000 — and revenues have to be split between theatres, producers, writers and other rights holders. But they amass very large sums over time. Avatar, the biggest-grossing film in Hollywood history, took $2.9bn at the box office. Phantom’s box-office sales are more than twice that — $6bn to date, while Les Misérables is just behind at $5.5bn.

“It isn’t the money, although we’ve made a lot of money,” says Nick Allott, managing director of Cameron Mackintosh Limited, his holding company. “It’s about what the business is worth to this country. I’m a government trade ambassador and I’m constantly saying to them, ‘Do you realise the size of the theatrical sector?’ You take War Horse from the National Theatre and One Man, Two Guvnors or Matilda, and then add in Andrew’s shows and ours. It’s a colossal contribution over a long period of time.”

But Mackintosh’s production arm is only one of three now grouped under Cameron Mackintosh Limited, which made pre-tax profits of £27.7m on turnover of £139m in 2015. “One of Cameron’s strengths is that he has constantly moved on, learning one part of the business and adding another part and another,” says Nica Burns, the chief executive of the Nimax theatre group. Mackintosh has outgrown his origins as a producer and now owns theatres and licenses musicals.

The theatres came first, starting with the Prince of Wales and Prince Edward, which he was offered in 1991 by Bernard Delfont, who ran First Leisure. He took a 50 per cent share in a deal to refurbish them and has steadily expanded into ownership since — now owning the Gielgud, Queen’s and Wyndham’s among his eight. “We kept being approached by people who said, ‘Look, would you like to buy these two? Would you like to buy this? So he was able to cherry-pick,” says Allott.

There is a natural tension between theatre ownership and production — the owner wants to rent out the theatre for as much as possible, and the producer for as little. “I never thought I’d own a theatre. They were always, I won’t say the enemy, but the people you had to deal with not to be taken for granted,” Mackintosh says. But by the time he acquired them, he was wealthy and could put more into refurbishment than his rivals, investing £45m in the first seven.

The biggest theatre owner in the UK is Ambassador Theatre Group, founded in 1992 and now majority owned by Providence Equity, a private equity company. Mackintosh does not care for that at all. “I think it’s deeply unhealthy, and so do most of the producers in London,” he says. “It’s very unhealthy for companies whose job it is just to make money for investors to own bespoke businesses because the pressure is on to make profits. When you start squeezing the product to keep the profit line up, it’s a terrible mistake.”

His indulgence towards his buildings has not noticeably hurt his bottom line, though. Delfont Mackintosh, his now wholly owned theatre group, made pre-tax profits of £14.2m on revenues of £44m in 2015 — a very healthy margin. Indeed, the West End as a whole has flourished in the past decade on rising ticket prices. Although attendance rose by only 1 per cent to 14.7m in 2014, sales rose by 6.5 per cent to £623m, with the average ticket price rising to £42.

Mackintosh’s third business is the least visible, yet in some ways the most remarkable — the licensing of secondary performance rights to 450 musicals, mostly owned by others. He has gradually taken ownership of Music Theatre International, a New York-based business that was started by Frank Loesser, writer and composer of Guys and Dolls, in 1952. He holds 75 per cent and by next year will control the whole business, which he is expanding globally. Copyright law requires that any production of a play or musical must have a licence, and MTI licenses 25,000 productions a year to 70,000 organisations, from regional theatres to amateur troupes and schools. Every US high school that puts on Hairspray or Annie, for example, pays MTI a fee of between $750 and $1,000. MTI keeps about 15 per cent, with the rest going to the writer and composer, or their estates.

In theory, schools and amateur productions could avoid that fee by buying the sheet music and ignoring copyright. But in the days of social media, when people boast on Twitter or Facebook that they are going to a show or are appearing in it, it is hard not to get caught. “Ours is the one art form that you cannot just steal and do it privately,” says Drew Cohen, MTI’s president. “You can download a song alone but the beautiful thing about our business is you need an audience.”

As a result, MTI is something of a cash machine. Even when musicals such as Little Shop of Horrors (for which MTI will rent schools man-eating plant props) are no longer on Broadway, they are performed hundreds of times a year. This brought in £22.5m in theatrical rights and licence fees to Mackintosh in 2015. That cash is likely to keep flowing for a long time, given the longevity of musicals and the fact that US copyrights last for the life of the author plus 70 years.

Gradually, Mackintosh has shifted the balance of his business from the risks of production through more stable theatre ownership to rock-solid licensing. He has protected himself against the decline suffered by those in show business when the spotlight finds a new star. “One of Cameron’s strengths is spotting how all the elements of theatre connect,” says Cohen. “Others live in the moment. Taking a musical from inception to licensing is like birth to annuity.”

. . .

“That’s a Cameronism,” remarks Richard Johnston. We are standing at the back of the circle of the Gielgud, where the play The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is on. He is pointing at three boxes of seats that Mackintosh noticed could be added by narrowing the corridor during refurbishment. It is one example of Mackintosh’s constant efforts to upgrade, improve, refine and get more money from his property.

It is also an example of a trait that can drive those around him crazy — he reserves the right to decide on everything. “I was in one meeting where he talked about the design of the loo roll holders for half an hour,” says Johnston. “Everything matters. He’s incredibly curious. If he comes into a room for the first time, he looks in every cupboard to see what could be done with it.”

Front of house at Delfont Mackintosh theatres is almost as minutely directed as the stage sets. Mackintosh found an old ventilation grille at the Prince of Wales before it was refurbished and got the architect to use the pattern for wall friezes in the auditorium. Yet the theatres still come second to the shows. “I’ve said to myself, ‘We need a decision on spending x million and he’s still locked in a room with a director and a piano,’” Johnston says.

“My skill is not to come up with an idea — I’ve never come up with an idea in my life,” Mackintosh says. “What I do is, once I’ve smelled there’s something original there, I’m good at working with the author and making that show as good as it possibly can be. I sort of beat it up in the nicest way. And I have the ability, even though I can’t sing and I can’t dance, to grunt and moan and shuffle out of time with the choreographer to construct the numbers right.”

His business is run from two Georgian townhouses in Bedford Square, where most of the 45 staff work. “I run my life as if it’s a corner shop, even though it’s become Selfridges. I like having friends around,” Mackintosh says. It is far from a modern open-plan office. An old brass chadburn — the device for a ship’s captain to signal speed to the engine room — sits opposite the reception desk. A staircase winds up to a warren of rooms on different floors.

They are filled with Mackintosh veterans. Nick Allott, who is now 61, has worked with him for 35 years — since just before the first production of Cats — and several others have been there for nearly two decades. “We’re still a pretty small group of people running quite a big business,” Allott says. Alan Finch, former chief executive of Chichester Theatre, will soon join as co-managing director, and Allott’s likely successor. “I’d quite like to spend more time on a beach,” Allott admits.

There will be no successor to Mackintosh. He lives in Somerset with Michael Le Poer Trench, a theatre photographer who is his long-time partner, and has no children. Two nieces through his two brothers work in the entertainment industry, but he does not intend to leave his business to his relatives. On his death, it will pass to his foundation, which last year gave £679,000 to theatrical and medical causes, with the proviso that it keeps the business running but does not mimic his role.

“I’ve been successful beyond any of my dreams and I realise my foundation is going to be worth an absolute fortune. But it can’t create any new productions. I don’t want anyone getting their hands on it and using the money to make new versions of my shows. They can be a co-producer but they’ll have to find another me. I want all the innovation to come from others.” It could be some time before it is tested, since, he says, “The greatest example I have in life is my mother. She’s 97 in January, sharp as a tack.”

At nearly 70, Mackintosh is as insatiable as when he asked to see Salad Days again as a child. When he bought Stavordale Priory, it came with 38 acres of land but he bought a neighbouring field, then another, then others until his estate reached the 1,630 acres on which 700 cows graze (he also owns 13,750 acres in the Scottish Highlands). “It’s organic and it’s really good dairy land. They’re very well-treated cows — they have mattresses,” he enthuses.

Mackintosh’s office in Bedford Square is lined with career mementoes. On a grand piano rests a commemorative bowl given to him by the cast of one London production of Oliver! The bowl shows Oliver in the workhouse, pleading for gruel: “Please, sir, I want some more.” Cameron wanted more, and he got it.

John Gapper is the FT’s chief business commentator

Portrait by Jillian Edelstein

Photographs: Rex; Cameron Mackintosh Limited; Alamy; Corbis; Alan Davidson/ The Picture Library Ltd;

Comments