Daniel Buren: reimagining space through stripes

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Visitors to Frieze New York this year will be expecting an understandably pared-down version of the sweeping, swarming art fairs we were once accustomed to. They may still, however, be taken aback by the restrained presentation offered by Lisson Gallery.

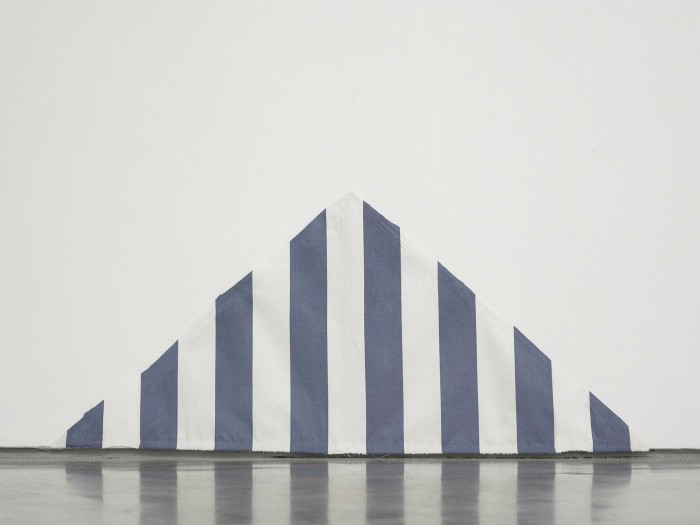

At a time when wall space at any physical fair is precious, just a few small strips of striped linen cut into triangular or wavy shapes will be positioned, sparingly, at the corners and around the edges of their booth. Their presence will probably do more to heighten the starkness of the white cube than detract from it, an intentional effect no doubt enhanced by social distancing.

Those with a passing familiarity with the artist, French conceptualist Daniel Buren, may also be miffed. A string of major public commissions have made his signature stripes hard to miss, but we are more used to seeing them in the form of dramatic, colourful and, in some cases, colossal statement pieces. Examples include the ticket hall at Tottenham Court Road station in London, the courtyard of the Palais-Royal in Paris and, New Yorkers may recall, his controversial “Peinture-Sculpture”, a 20-metre banner of blue and white stripes that briefly dangled down the rotunda at the Guggenheim. Installed for a group show in 1971, it caused complaints and was quickly removed.

When I speak to Buren over Zoom I find him affable and prone to finish statements with a chuckle. At the age of 83, his dark eyebrows produce a striking contrast with his thick white hair. I quickly get the impression that he has spent decades patiently fielding questions about his work from people who don’t quite get it. To help me understand the works at Frieze, made in the 1960s and ’70s, he takes me back to the early days of his career.

Where most artists cite a formative period of artistic training, Buren brushes over several years as a student in Paris to tell me about a job he scored soon afterwards, painting murals at a hotel in the US Virgin Islands. The large-scale abstract works helped him, in his words, “to get clean” from traditional art historical influences that would otherwise have taken years “to wash out”.

Buren went on to form an association with some of his peers and “decided to really shake up the situation in Paris,” he says. Together they staged farcical exhibitions, including one in which they took down all the artworks on opening night.

This impulse to question and critique the art world was keenly felt, but the turning point came in 1965 when Buren spotted the striped linen used for window awnings at a market. He was drawn to the stripes because their uniformity was “totally uninteresting and completely banal”. Fearful that the materials might be perceived as ready-mades, he added his own barely perceptible interventions in white paint. Remarkably, these muted gestures would, in 2007, win him Japan’s prestigious Praemium Imperiale for painting.

Buren’s interest in repetition and reduction, to move beyond traditional pictoriality towards a new neutrality, chimed with minimalist experiments happening at the same time in New York. He puts this down to the French notion of “l’air du temps”, or a mood of the time that affected many people unknown to each other.

As he began working with stripes, which Buren calls a “visual tool”, he realised “this tool is so minimal, so uninteresting that what becomes interesting is where the tool is posed. When you put such a tool in two different spaces, it’s not saying the same thing. How is that possible?”

Having discovered the power of this tool, Buren ran with it. Unable to afford rent, he closed his studio and took to the streets, where Parisians began to see his “Affichages Sauvages”, striped posters, crop up over billboards. “That was the beginning of what I consider a very serious work”, he says.

As is often the case in our conversation, Buren recognises the far-reaching consequence of these early decisions but pins them primarily on circumstance. “Of course it wasn’t a programme, but when I see it in a retrospective it looks well-thought out. So does the idea of quitting the studio, but for me it was interesting to quit the studio to analyse why an artist needs a studio, not because I thought I would never have a studio again.”

By accident or design, the decision to produce art on the street was the first step towards Buren’s concept of working in situ. “When I speak about ‘in situ’,” he says, “it means the work is done at a certain place and is playing with that space and the people who go there.”

The neutrality of Buren’s stripes are intended to draw our attention to their surroundings, which is what makes them so effective in museum and urban settings. “Everything that makes these works possible is not mine. They have nothing to do with my work! So what I consider a work of mine, as I present it to the public, is a total integration of a lot of foreign objects or foreign architecture or foreign colour.”

Though doubtful about even calling himself an artist — “if you use the word “art” it just ends the conversation” — Buren was soon invited into art institutions. A 1980 group show at Lisson included “A Work in Four Parts for One Wall”, one of three works that will be faithfully restaged at Frieze. “They were more or less a starting point for all the experimentation that I did”, he says of these rare early works which saw him cut up the striped linen into pieces and use them to frame a wall. The effect was to trick the viewer into paying attention, not to the stripes, but to the surrounding gallery space.

“The stripes are really recognisable. So people who know my work can connect them to other pieces. There is always a connection to my other works”, says Buren. In this sense, the pieces at Frieze can be seen as early fragments of a larger conceptual work that is not yet finished.

Asked what will be different about their exhibition at the fair, he says “the elements will be presented exactly the same, although the wall might be bigger or smaller, which would change the physicality of it. But even if the wall is the same, what’s the difference between these two things that look very much the same? Forty-five years. Nothing could be more different than 45 years, so the piece has changed.”

He has a point. When the works were first exhibited, Buren was still making a name for himself and the world was getting to grips with conceptual art. Some 45 years later, we now see the same works through the lens of the momentous and historic projects he has realised since. As a viewing experience it will indeed be at once very similar, and yet completely different.

Comments