Patients fall victim to health ransomware

Simply sign up to the Cyber Security myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

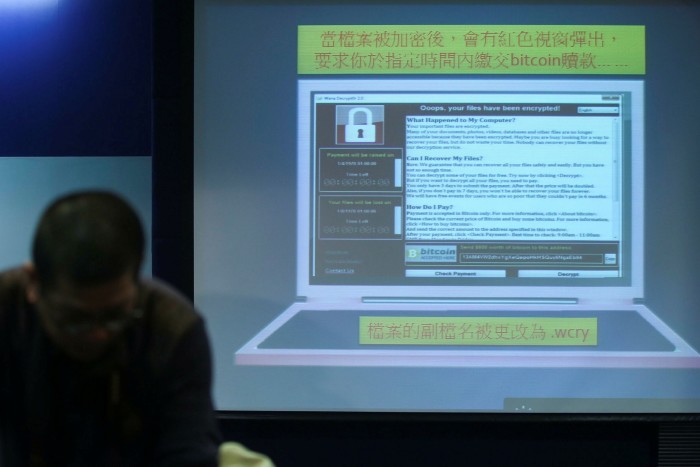

The WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017 caused severe disruption to the NHS, costing the UK’s health service £92m and leading to the cancellation of 19,000 patient appointments.

The attack, which stemmed from a malicious code placed in commonly used software, highlighted how disruptive ransomware can be for health systems and prompted a renewed focus on cyber defences.

The NHS is not alone. There have since been attacks on a variety of healthcare organisations around the world including dental practices, private hospitals and smaller clinics.

In one case in Finland, the confidential treatment records of thousands of psychotherapy patients were hacked and leaked online — many patients were blackmailed to keep the data private. In September 2020, a ransomware attack took down a chain of more than 250 US hospitals and clinics.

Apart from blackmailing patients to keep data private as in the Finnish case, hackers can also use data for identity theft.

“There has been a significant fallout from WannaCry — the NHS is now much more concerned with how people are handling security in their individual organisations,” says Adrian Byrne, chief information officer of the University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust (UHSFT).

“There’s more monitoring, expectations to achieve security standards, more investment and more awareness.”

A September 2020 report from Veritas, a data protection company, found that 39 per cent of healthcare companies around the world have been hit by a ransomware attack at some point.

While businesses and organisations are affected by cyber attacks, it is ultimately patients who suffer. The WannaCry attack resulted in services being taken offline, forcing the delay or cancellation of healthcare procedures.

If healthcare workers are prevented from accessing patients’ data, it could also stop them from being able to carry out procedures or provide patients with test results. If the data is manipulated by hackers, it could lead to a misdiagnosis.

Alterations can be made to physical devices through cyber attacks that could make them unsafe, according to Howard Holton, an analyst from GigaOm, a technology research and analysis company. “If we look at the risk of an MRI machine, X-ray machine or dialysis machine, the potential damage to the patient is huge. Life-saving machines could also be turned into non-functioning devices, leaving patients without access to treatment,” he says, adding that such attacks undermine patient trust in the health

organisations.

“When you’re engaging with a health service, that’s when you’re often at your most vulnerable and where you want to know that the security is robust,” says James Fleming, director of IT security at the Francis Crick Institute, a charity that uses pseudonymised data from the NHS to research diseases to help prevent, diagnose and treat illnesses.

In addition, there are mental health implications for patients; delayed care is likely to create anxiety and uncertainty, while being blackmailed to retain the privacy of data will cause fear and embarrassment.

According to the 2020 Harvey Nash/KPMG CIO Survey, more than half of IT leaders in the healthcare sector said their top technology investment was security and privacy.

Despite this, more than a third experienced an increase in cyber attacks during the pandemic, mostly from phishing or malware, suggesting that the shift to remote working had increased exposure from staff.

While the onus is on businesses to maintain investment in technology, many attacks are the result of staff making mistakes or being tricked into clicking on a link or handing over data — not all of which can be prevented by new technology.

According to Mr Fleming, patients need to have “a basic understanding of their own data, and the understanding of the services they sign up to online and the use of their data”.

He adds: “We also need to move the debate on from believing that only health services should see my data — people may want their data to be

used effectively in other ways but it’s a hugely complex answer to make that happen.”

For example, there is no portal that shows UK patients where all of their private medical data has been shared.

For the health organisations, it is a question of “when” not “if” the next attack or data breach will occur, says Mr Byrne of the UHSFT.

“There will be future security events, because it’s not just an individual in his bedroom [launching malware]. There are state actors involved in these things,” he says.

Comments