Splendid isolation: the long way home

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

One balmy black-sky night last autumn, at a beautiful hotel in Laos, my partner of six years – to whom I’d been engaged for 18 months – took my hand and said: “I don’t think I want to marry you any more.”

Two facts about this exchange. One, it took place the day before my birthday. (I know.) The other – which mitigates somewhat the scorch of the first – is that I half knew it was coming. It was part of a long and complicated conversation. And, while it took my breath away (literally – because how many exact sentences are there among all the possible sentences on Earth that fall so squarely under the heading of Things You Never, Ever Want To Hear Said To You?), it didn’t take me by surprise.

We met in southeast Asia, where he was, and is still, based. After more than a year of long-distance commitment, I moved from London to Singapore to live with him. We had a lovely little flat, a glass-walled box in the sky overlooking the city’s botanical garden, and a few years of real happiness – the springtime of our together-ness, I think we understood even then, vastly extended by the time we spent apart as a result of our work.

From the start, I was indifferent, leaning to sceptical, about marriage. Why, in my mid-40s? When I’d gotten this far without doing it? We got engaged eventually, though, because I loved him and it was important to him; and also, if I’m honest, because I feared he’d move on if I didn’t. But a 2019 full of challenges, including a disruptive move from Singapore to Bangkok, had seriously frayed a bond already worried away at for some time by career demands, tricky family stuff and garden-variety familiarity.

Initially, the brutal birthday semantics aside, it was a very gentle separation. We agreed to take time adjusting to our new uncoupled reality; I would move after the New Year. When, a few weeks later, circumstances came to light that instantly, explosively scuppered any possibility of continued gentleness (I’ll entrust the details to the reader’s imagination), we were spared the misery of constant cohabitation by manic travel schedules.

I cried, and packed. I cried at 39,000 feet, in seat 44J. I cried buying tea at Mariage Frères in Paris. I cried in the queue at the Pret A Manger on Cannon Street, and in the ladies’ room at FT HQ in Bracken House. I felt less outrage than I’d expected to, and a far greater sense of failure. I still feel a messy alchemy of grief and relief that is painful to untangle, and to own.

I packed and unpacked (in our guest bedroom, which I’d moved into) around each long or short work trip. Then I’d sit at the kitchen bench with tea – or wine – and mentally pack up what had come to Asia with me. My Wishbone chairs, hundreds of books, vintage bedlinens from the Bridport market in Dorset. I catalogued the things whose significance preceded us, that were ineluctably mine – and as such, like me, no longer belonged in this picture.

I had already danced around the question of where I’d move. Back to London? He wondered. No, I said: Italy. Yes, I know, everyone from Lord Byron to Liz Gilbert has gone to Italy to subsume their malaise in its beauty, I know, how banal. But Italy and I have history. I studied there for a couple of years in my early 20s, I speak the language fluently and have friends up and down the peninsula. And in an adult life that has taken on overly migratory qualities I’ve alighted there more than anywhere else.

My imagination was too overtaxed – sifting forensically through the half-knowns and he-saids of our fallout – to generate even an outline of what a new life there would look like. But I left anyway, in mid-January, with three suitcases. My things would have to follow. “Home” would be provisional for a while; I’d handle it. I’m used to being on the road, with suitcases.

Six weeks later, I was packing again in Rome, for a brief work trip. I had an address, albeit a temporary one. A permanent residency application was in the works. Throughout February coronavirus had pressed westward from Asia, bringing lockdown to cities in the north. Roman bars and restaurants were on curtailed hours; the streets were emptier each day. Part of me clearly saw the delicate outline of my future dissolving into a subfusc haze of uncertainty. But I had a work trip to think about, and it was the easier thing to focus on.

On 6 March I left for Spain. Then things began happening very fast. Italy closed its borders to all non-citizens and permanent residents. With no long-term visa in place yet, I was effectively locked out. Madrid imposed quarantines and a border closure in Spain seemed imminent. I thought for about two minutes of going back to London, but I’d long since given up my flat, and it was hardly the moment for short-term house-hunting.

So I bought a one-way ticket to San Francisco, landing hours before the US closed its own borders. I rented a car and drove south to the Monterey Peninsula, where my mother and father live in a cottage not far from the ocean. The plan, inasmuch as there was one, was to stay with them for 10 days or so, then maybe wander north to my brother’s place in Marin County, or south to LA to see friends. I’d be an unobtrusive guest, for the handful of weeks I still thought we were all talking about back then; all I had with me were my laptop and a smallish suitcase.

Six days later, my home state became the first in the US to issue a mandatory shelter-in-place ruling. Which is how I ended up where I am now: in California, with my entire life distributed between a flat in Rome and another in Bangkok. Newly, quite harrowingly single. About to turn 50. Living with my parents.

When I made a self-pact in January to confront whatever my future might hold with Zen equanimity, I don’t have to tell you a global pandemic wasn’t in the catalogue of possibilities I’d entertained. Of course, no one saw this coming (bar a handful of vigilant epidemiologists to whom a lot of us really wish our governments had been paying more attention). Countless lives have been upheaved, many thousands of them far more severely than my own. All of us have been tossed alarmingly outside our comfort zones; now we are all fixed, alarmingly, in place.

Eight weeks in, here’s the interesting thing: my situation is not alarming. It’s not the Netflix tragicom-series pitch it probably half-reads as above. It is comfortable, and it is eminently comforting. This is partly because my late-seventysomething parents are genuinely lovely people, who met the prospect of their adult daughter – a potential virus carrier, it should be noted – landing on their doorstep from Europe with her one suitcase (and a lot of anxiety about her eventual income stream, and no real idea of how long she would be in residence) with compassion, grace and generosity. It could also have to do with the fact I was still in mid-air from the impact force of my own personal upheaval when full global upheaval hit, which has left me in a more existentially bendy state – all the better to abide what I could never have seen coming.

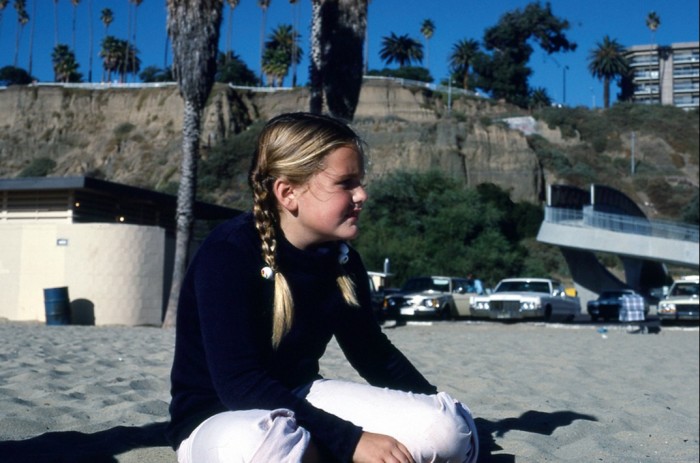

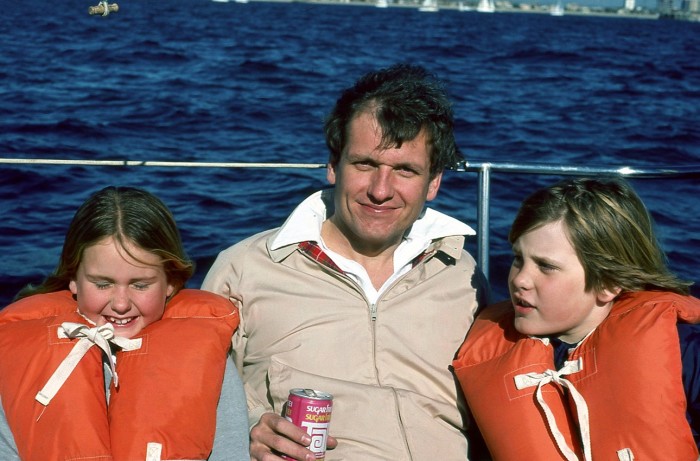

My parents bought their house in Carmel in the ’80s, and moved up full-time from Los Angeles when they retired several years ago. Though I grew up in LA, I have deep sensory memories from childhood of the long drives north on Highway 1. I recall anticipating the changes in atmosphere, temperature and colours where the topography begins to buckle and shear skyward above Cambria at Big Sur‚ the place that to me demarcates the physical and deeply cultural northern-southern California divide. California’s central coast is one of the most spectacular landscapes in the US. (That’s not personal bias talking; Google it, or watch Big Little Lies again). It’s a locus of majestic Pacific Ocean vistas and counterculture lore in near-equal measure. Carmel, which sits where Big Sur peters out into the peninsula, is sufficiently exurban that I can walk its cypress-lined paths and lanes for miles without breaching either the shelter-in-place dictate or the social-distancing one. Half a kilometre from our house is a 34-acre nature preserve, a Middle Earth fairyland of redwoods and climbing vines and sinuous coastal oaks draped in Spanish moss. A trail system runs through it, used in the 18th century by the Franciscan monks who founded California’s famous missions. Carmel State Beach is a shallow mile-long crescent of lime-white sand, a perfect running beach at low tide and an off-leash Valhalla for dogs. At the time of press, it’s one of the few in the state that hasn’t been closed. I miss Italy, often and sometimes acutely. But it feels a bit churlish, bemoaning the distance between me and the saffron-amber-oxblood palette and old-stone smells of my truncated life there, when I’ve had the enormous privilege of this nature in which to roam.

It has been years since I’ve been in one place long enough to watch an entire season unfold (Singapore, one-and-a-half degrees north of the equator, has no seasons). I’m bowled over by what a spectacle this spring is, though my mother and father insist it’s only moderately more extravagant than usual. Swaths of orange poppies have bloomed, festooning the shoulders of Highway 1 like bunting; the ice plant along the beach is stippled pink and yellow with blossoms; lupin runs riot in Carmel Valley, carpeting entire acres of hillside in blue.

Every fourth or fifth day until mid-April, rains rolled in, imparting a bit of cinematic bombast to the skies above the Santa Lucia mountains, which ripple with grass so green they could be in Cork. The smells are ur-California, a Proustian barrage that pulls me back to my childhood on every morning run: the loamy black soil of pine forest, the acrid new sagebrush of the flats. The storms wash up huge ropes of kelp; the fug of it mixes with the brine of the ocean in my nostrils and the back of my throat. Each day, the shape of the beach is minutely altered. I’m deeply out of practice at stasis; eight weeks is as long as I’ve gone in ages without travelling. Spring’s progression is an object lesson in temporality, and in being where I am.

Bloom where you’re planted, I read on a bumper sticker a few weeks ago as I drove to the village’s lone pharmacy. The pharmacy is a small, mom-and-pop business, but its high-low merchandise mix is a window on the demographics of the peninsula – $24 Marvis toothpaste and Claus Porto soaps alongside the nappies and antacids. The Monterey Peninsula is its own unique iteration of America. It’s a well-off, educated catchment in a state with the world’s fifth largest economy; the gated community of Pebble Beach, with its exclusive golf clubs and annual vintage-auto concours, testifies to this. But much of the rest of it is deep coastal-California blue. It punches above its weight culturally; Carmel, population less than 4,000, has an annual Bach festival, and a film festival, and three performance theatres. David Sedaris regularly reads from his work at the community centre, where Willie Nelson is also known to headline. A local high school broadcasts the BBC World Service every day on its student radio station. There are half a dozen weekly farmers’ markets within an eight-kilometre radius of each other, and probably as many vertically integrated cannabis boutiques.

The houses tend toward cottages and California bungalows; some of them, like my parents’, are creeping up on a century old. Some are given silly names; some have gorgeous gardens. Some have sprawling new additions and Tesla Model S’s parked in their drives (Carmel has become a popular second-home destination with the newly minted wealthy from the Bay Area). For the most part, everyone grooves along. The singsong “Hi-iii”s issue from behind masks or bandanas these days, but are no less friendly. They still startle me, who left California, and greeting everyone I see on the street, 26 years ago.

I love this place, which is and isn’t my home. Los Angeles is where I was born, but no one in my family lives there any more. In my adult life, this cottage in Carmel is the address that corresponds most closely to the idea of where I come from. I’ve slept these last eight weeks in a downstairs bedroom that has been “mine” since I was at university, though there have been years of my life when I didn’t come here at all. I know the knots and grain of its ceiling beams. I lie in bed now, basically a middle-aged woman, and remember staring up at them at 20, cataloguing the places on the map of the world I thought I might like to call home.

Because I did always want to live everywhere. And succeeded, to some degree; in the past 15 years I’ve had addresses in five countries, and travelled to dozens of others. But it transpires there’s an occupational hazard of itinerant life, one I wish I could have warned that 20-year-old about: a kind of free-floating homesickness. It’s been the privilege of a lifetime to immerse in parts of the world so far away from the one I was born in. But to live in many elsewheres is to feel slightly displaced everywhere; even the place that’s putatively home.

As I reconcile my increasingly frail parents in a landscape I haven’t been so intimate with since I was a child, I’m homesick for the days when they roamed it tall and young and smiling. When I inhale the Pacific, I touch the wild joy of my five-year-old self; then I hold my mother’s hand, small and dry and fragile as a wren, and know it’s true that time does go much faster when we’re older.

And now we’re all preparing to re-enter the world, which we hope is returning to some semblance of normality. Soon, probably within a few months, some of us will be travelling again. I’ll get back to Rome eventually, and my wonky little flat, where I expect to find every last thing I own furred with centimetres of ancient dust. I’ll get to work rebooting my life there – though I’ll never precisely resume the one I’d started, because I suspect the entire world has shifted slightly, and the future with it.

I am making something of a pact with myself: try to travel a bit less, try to stay a lot longer. To find a way to make that work with work. But I love the elsewheres of this world, and getting to them, and writing about them. I’m fairly sure my future will still include living out of a suitcase once in a while (though I hope fervently to avoid ever again having to parlay one originally packed for a five-day trip into a two-month sojourn). In the meantime, I want to pay attention to what, and who, is around me now, here where I’ve been sheltering, and sheltered.

Comments