Fear, loathing and automation

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Recently, I took part in The Future of Work in America, a seminar including economists, policymakers and consultants, to discuss the vexed question of automation and jobs.

There were plenty of predictions that will alarm politicians – and voters. McKinsey forecasters reckon that between now and 2030, tens of millions of jobs – or, at least, the ones that people currently get paid for – will be performed by robots and digital networks.

Thankfully, McKinsey stresses that digitisation will create so many new jobs that there will be “net positive job growth for the United States as a whole through to 2030”. But this process will be desperately – dangerously – uneven. People holding only a high-school diploma or less will lose their jobs four times faster than the average, because this new work will be skilled.

Some demographics will be hit particularly hard, with 11.9 million Hispanics and African Americans, 14.7 million young workers and 11.5 million older workers seeing their jobs replaced.

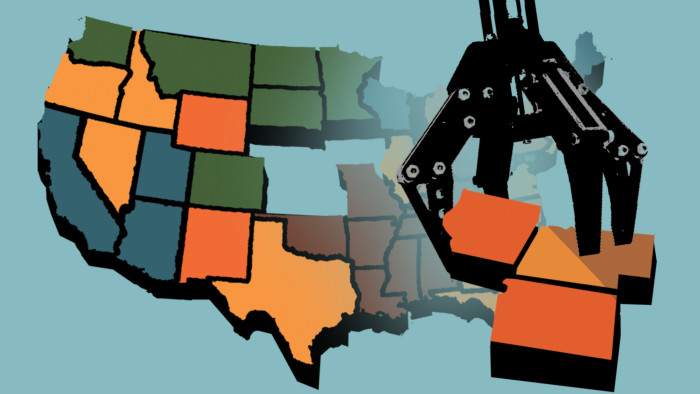

McKinsey believes that 25 megacities and urban hubs will account for almost two-thirds of future job growth – even though they hold just under half of the American population. The future of the labour market, in other words, is likely to be a tale of feast and famine.

So far, so unnerving. But as I listened to these predictions, I thought: our era is not the first to have seen jobs destroyed by technology. Innovations such as electricity, railways, the telegram and the steam engine had a similar effect in earlier times.

Data from the Milken Institute, for example, suggests that while just 2 per cent of the US population lives on a farm today, that figure was 40 per cent in 1900 and 98 per cent in 1800.

“How much faster is the displacement process than before?” I asked the seminar. I presumed that the answer might be anything from “twice as fast” to “10 times faster”, given how much panic there currently is around automation.

There was a long silence in the room, and then the assembled economists admitted that insofar as they could tell – and it is fiendishly difficult to make precise comparisons due to the lack of granular historical data – there is little evidence that the process of technology-driven job displacement has actually speeded up in a significant way.

I was stunned. For if that is correct, it begs another question: why is everyone so worried about technology right now? The seminar participants proffered some ideas.

Maybe pundits are scrambling to find something to blame for the rise of populism. Perhaps social media and the advent of the economics and consulting professions have made it easier to track job losses. (When agricultural jobs were being lost on farms a century ago, there were no McKinsey consultants to quantify them.)

However, perhaps the most likely culprit is labour mobility – or, more accurately, the lack of it. A century ago, American workers often went wherever jobs could be found. The mantra “Go west, young man!” (in search of opportunity) defined the nation’s image. But today, McKinsey notes, “geographic mobility in the United States has eroded to historically low levels”.

More specifically, while 6.1 per cent of Americans were moving between counties or states each year back in 1990 (and in previous decades, this was almost certainly far higher), in 2017, that figure dropped to 3.6 per cent. And when workers do leave depressed areas today, they typically relocate to places with a similar profile rather than to megacities or high-growth hubs.

Why? One factor is probably the country’s ageing population (younger workers tend to be more mobile). Another is high rates of home ownership (property can be hard to sell). A third is that states have introduced licensing requirements for many jobs in the past decade that make it difficult for people to seek work elsewhere. A fourth issue is that the cost of living in urban centres is so high.

Finally, McKinsey suspects there is also “a growing cultural divide” – or polarisation – in America that makes workers less willing to leave their communities.

Either way, if lack of mobility is the key reason why automation is creating so much fear and, as I suspect, fuelling populism, that raises a crucial policy question: when job losses do occur, should policymakers create more jobs in those distressed areas? Or make it easier for people to move?

Few politicians will publicly embrace the second idea. After all, they generally get elected on a local political base – and almost nobody wants to challenge local pride. But I have a feeling that unless the issue of geographical mobility receives proper attention, the automation factor will continue to spark political fear.

Call it, if you like, a great irony of our modern age. Cyberspace was supposed to make us all less shaped by physical geography – but the reverse might actually be true. And if McKinsey is correct about automation, this problem could soon become even worse.

Follow Gillian on Twitter @gilliantett or email her at gillian.tett@ft.com

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments