Bridget Riley: ‘I keep trying to push age away’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Although Bridget Riley’s Victorian house in London is redolent of the Georgian architecture in Bath, her uncompromising commitment to modernity becomes clear when I enter the spacious ground-floor room. Vibrant paintings alive with striped colours pulsate on the white walls, and Riley greets me with an irrepressible sense of energy. Now 87, and dressed in a simple white shirt with black trousers, she looks ready for action.

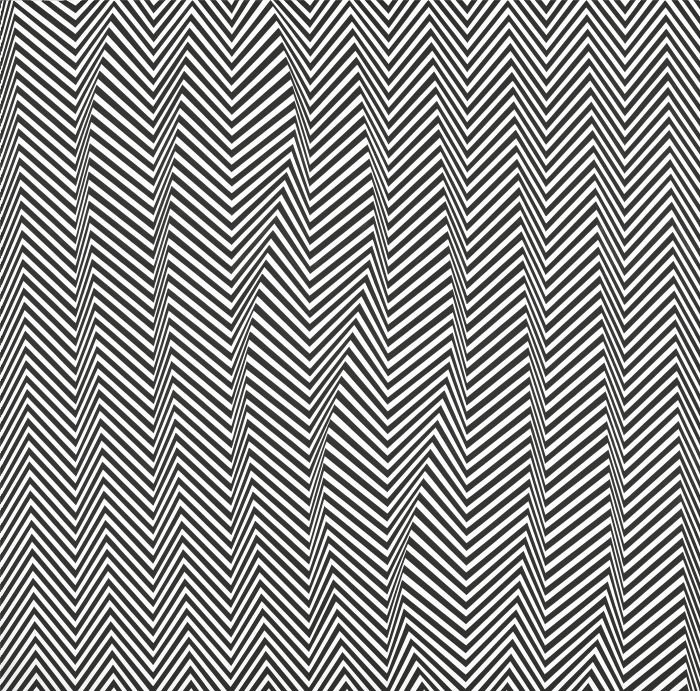

Today, her excitement is focused on a lucid model of the Sprüth Magers gallery in Los Angeles, where her large exhibition Painting Now will open on November 16. Riley encourages me to kneel down and gaze through the model’s front door and windows. The spacious interior is dominated by a gigantic wall-painting called “Quiver 3”. Its strong emphasis on black-and-white forms is redolent of her monochromatic paintings of the early 1960s, when Riley suddenly gained an international reputation as an audacious Op artist. She shows me a reproduction of her 1962 painting “Tremor”, explaining that its powerful emphasis on the dynamics of optical stimulation was inspired by “the leaves on poplar trees — the sensation they gave me when they quiver and tremble in the wind”.

Smiling, Riley insists that “Nature is much better than anything I can do.” And she recalls the astonishing quality of the light in Los Angeles: “I haven’t shown there for 40 years, but I still remember the amazing ocean. I’ve always been moved by everything the sea does, with clouds, reflections and the good temper of the sunlight. It kindles life, and I have a feeling of optimism about LA. Tony Curtis bought a painting from my show there, and he used to take it with him when he travelled.”

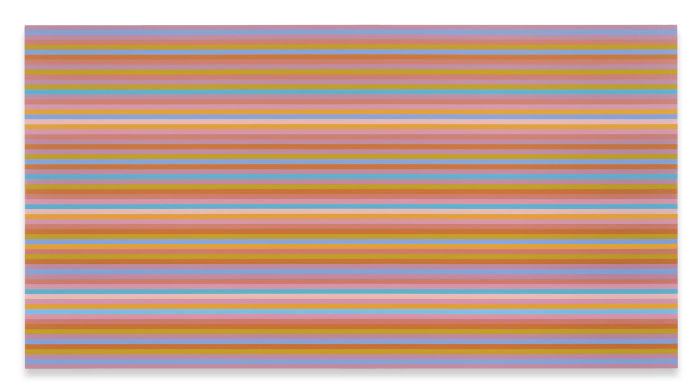

Returning to the model of the Sprüth Magers gallery where her new exhibition will be held, Riley shows me reproductions of the “Measure for Measure” canvases she is displaying there. “In the early summer I went to my studio in Provence and did a great deal of work developing these paintings,” she says with enthusiasm, waving her arms around to express her feeling of delight. (Riley designs her pictures; the final work is produced by her team of studio assistants.) “I can’t make the journey to LA this time. Not being able to move for so long in a plane is bad for my back. It’s a great shame, but I do want to continue working. I keep trying to push age away. I still have such a lot I want to make, and I’m trying like mad to do as much as I can!”

Pointing to the benches placed in the LA gallery’s rooms, Riley insists that viewers should be encouraged as much as possible to sit down and enjoy “the gentle art of looking. People rush through museums and galleries too much, so it’s absolutely important to have lots of space around a painting. It helps people look at an art work and wonder a bit. Gradually it unfolds, but the process takes time.

“The first room in my show will have a group of paintings which make comments on each other. They are called ‘Memories of Horizons’, a quote from a poem by Mallarmé in which a long stream of consciousness tries to answer the question: what is the world?” Riley smiles again. “Now that I’m older, I appreciate a lot more the structure of poetry and what it releases — turning over a feeling or a thought and finding a different way of expressing it.”

Just how far Riley has progressed as an artist will be disclosed in her LA show by the inclusion of a small 1960 painting called “Pink Landscape”. “I made it in my very first studio, in the Earl’s Court area,” she recalls. “I’d had many years of frustration and despair sometimes, not being able to find a way somewhere. I needed a breakthrough, and ‘Pink Landscape’ was a hinge painting. Seurat had an enormous influence here, helping me move towards what one critic called ‘separate touches’, uncovering something that had been there all the time. It was a hunt, a chase, and tremendously exhilarating. I was fired with energy.”

During the 1950s she had been a figurative artist. And high up on a wall in her house I find a 1956 drawing of Riley’s mother Louise. Severely simplified and yet filled with warmth, this Conté crayon sketch shows how important draughtsmanship was to the 25-year-old Riley. She tells me that her mother and sister were both “marvellously patient, because I drew them a lot”.

Riley takes me out into the back garden, which she describes as “overgrown, which I like”. Pausing in the middle and gazing around, she exclaims: “Look, it’s a bower!” Her mother created it and “left me this wonderful garden with very little work attached”. Pointing towards an enormous tree at the far end, Riley explains that “my mother brought it here in a pot, and I like so much the way the light comes through.”

Sunshine played a crucial role in stimulating Riley’s vision as an artist, especially when she moved on from black-and-white paintings to exploring vivid colours in her subsequent work. At that time, she was one of very few prominent female painters in a male-dominated art world.

But when I ask if she ever found this patriarchy oppressive, Riley shakes her head: “I was extremely fortunate growing up during the second world war, from that point of view. Class structures disappeared under the demands of that time — we had to make a superhuman effort, all hands to the wheel with Wrens, Land Girls and women working even in the most dangerous factories, too. Gender differences absolutely did not operate, and comradeship was very intense.

“After the war we all wanted to do something with the peace. It sharpens you. In 1949 I went off to study at Goldsmiths College wearing a pair of corduroy trousers and a man’s shirt. None of this gender business occurred to me!”

Suddenly, a powerful sunbeam bursts through the midday London clouds. Even though we have left Riley’s garden and gone back inside the big room, this revelatory autumn light emblazons everything in the room, especially her radiant paintings. Riley shows no sign of slowing down as an artist, and she loves working on immense wall-sized images: “I’m opening my work out on a huge scale now, far bigger than is possible on canvas. But wall paintings are not a separate category in my work — each one has been an extension of what I’m doing in the studio. I still spend as much time there as I can, and I like it silent. But I enjoy listening to music when I’m not working. Mozart is my favourite: he is joyful, and that’s so affirmative because he knew all about difficulties. One thing I do love is courage.”

November 16-January 26, spruethmagers.com

Comments